Blog Post

Rod Dreher’s Manual for Christian Dissidents (and predictions for the future)

By Jonathon Van Maren

I’ve reviewed all of Rod Dreher’s previous books with the exception of How Dante Can Save Your Life (which I also enjoyed.) I reviewed Crunchy Cons here, The Benedict Option here and here, and The Little Way of Ruthie Leming here. I look forward to his next offering.

***

A few years ago while visiting Budapest, our young tour guide stopped on the steps of St. Stephen’s Basilica (named in honor of the first King of Hungary, whose hand is housed in a reliquary within) to tell us a personal story. She was the first member of her family to attend university, she said, because her family was Christian—and the way that the Communists “dealt with” Hungarian Christians was by implementing policies that forced them to the margins of society. You were permitted to pray at home, and even to get baptized and attend church. However, you had a choice. “You could be a Christian,” she told us, “Or you could be successful.” Case in point: Because her family was Christian and she was baptized, her sister was the first member of their family to be able to attend university, after the fall of Communism.

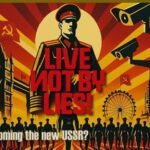

This, Rod Dreher told me in an interview, perfectly sums up the soft totalitarianism that he believes will come to the West. His new book Live Not By Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents is a follow-up to 2017’s The Benedict Option and is divided into two parts. The first half of the book makes the case that the United States—and perhaps much of the West—is in a “pre-totalitarian state.” The second half of the book features interviews and insights of Christian dissidents who clung to their faith and their families during the long, dark night of Communist rule. We will need to rediscover these truths in the days ahead, Dreher believes. We are heading into a long night of our own.

Dreher’s analysis is characteristically gloomy but detailed enough to give even an optimist cause for pause. Using Hannah Arendt’s study of totalitarianism, he analyzes current conditions in the United States. “We are living under decadent, pre-totalitarian conditions,” he noted. “Social atomization, widespread loneliness, the rise of ideology, widespread loss of faith in institutions, and other factors leave society vulnerable to the totalitarian temptation to which both Russian and Germany succumbed in the previous century. Furthermore, intellectual, cultural, academic, and corporate elites are under the sway of a left-wing cult built around social justice.”

Dreher lists six reasons that he believes America is a pre-totalitarian state. He highlights widespread loneliness and social atomization (brought about by massive family breakup and exacerbated by technology), a total loss of faith in institutions and hierarchies; a destructive impulse that drives a desire to tear things down; the rise of propaganda and both a willingness (and desire) to believe ideologically convenient lies; polarization as a result of a hardening of divides along ideological lines; and finally, valuing loyalty to a set of ideological principles (wokeness) over expertise, something that particularly afflicts universities. Even Big Business, sensing the changing cultural winds, is getting in on the game.

Corporations, he writes, have also become woke—and are now exercising phenomenal, hitherto unheard of power. Global mega-corporations are more powerful than many countries. Walmart has more annual revenue than Spain and twice as much as Russia. Exxon Mobile is bigger than the economies of India, Norway, or Turkey. And most forebodingly: “In an America that now runs on the Internet, five companies—Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Google—have an almost incalculable influence over public and private life.” In Dreher’s opinion, the framework for a Chinese-style social credit system already exists. It is known as “surveillance capitalism,” and it is orchestrated by woke corporate leaders who don’t just want money—they want to shape the future.

“In 2003, Google pioneered a new way of making money by gathering up tons and tons of extraneous data from the way people use the Internet,” he told me by phone. “Of course, smartphones added to it. What they did was figured out from all this data and applying algorithms what people want, what they want to see, what they might want to buy. All of this was to try to figure out how to better serve people as customers. The problem with this is that it also gives these companies a really good idea of how to manipulate people. In Communist China they do the same thing, except the state uses this data to force conformity on people by giving them greater access to middle class comforts if they conform—and cutting off their access if they fail to conform. We have the same thing going on here right now in America, but the government isn’t seizing our data. We’re handing it over freely to big corporations.”

In short: “Your private digital life belongs to the state and always will.”

This, Dreher told me, means that it wouldn’t take much for a social credit system to be implemented. “The data are already there. In a low trust society where people don’t know who they can believe in, they’re going to want some kind of objective standard of trust. This is why the social credit system in Communist China has actually been fairly popular with the people. Forty, fifty years of Communism destroyed social trust. People turn to this electronic system to know who is trustworthy. I think that the younger generations, the millennials and Gen Z who have dramatically lower levels of social trust and who have been so alienated thanks in part to technology—smartphones and social media—they’re going to be sitting ducks for this sort of thing coming down the pike.”

The American population—and this goes for many Western peoples—have been “wholly propagandized…and demoralized by hedonistic consumerism.” Materialism, Dreher believes, is even more destructive than Communism. Communism is so obviously incompatible with Christianity that it forced Christians to make a clear choice (Soviet Russia even had organizations like the League of the Militant Godless, which went door to door like thuggish atheist Mormons.) Materialism, on the other hand, can seduce Christians into lives of comfort. Once Christians are living like the rest of the hedonistic culture, with Netflix and PornHub and technology and social media snatching away every solitary meditative moment and keeping our minds buzzing with trivial distractions, they have essentially been colonized without noticing.

Christians in the West are often just as spiritually lifeless and materialistic as their secular counterparts, says Dreher. We watch the same sports games, movies, TV shows; run the same rat races; have the same conceptualization of the “good life,” with maybe some church on Sunday tacked on. In short, we are utterly unprepared to make sacrifices—big or small—for our beliefs the way Christians in Communist countries were forced to. Dreher quotes Lewis’s famous encapsulation of the Christian life to highlight the contrast: “Christianity is the story of how the rightful king has landed, you might say landed in disguise, and is calling us all to take part in a great campaign of sabotage.” The Christian life, in short, isn’t supposed to be comfortable. What will happen one day soon when in the West, Christians are presented with the choice the Hungarian Christians once faced: You can be successful, or you can be faithful?

First and foremost, Dreher writes, Christians behind the Iron Curtain refused to live the lie that Communism demanded. “A person who lives only for his own comfort and survival and who is willing to live within a lie to protect that is a demoralized person,” Czech dissident Vaclav Havel once wrote. Dreher interviewed dissidents from Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Russia, and elsewhere, and through hearing their stories, pinpointed the bedrock principles that allowed them to stay strong during the years of persecution. He names six principles, and none of them are political: Value nothing more than the truth (refuse to live a lie); cultivate and pass on a cultural memory (refuse to let the state redefine history); develop families as cells of resistance (nothing is more important than your children); resist evil through prayer; resist the “idolatry of comfort”; and rely on Christ alone as the foundation for salvation. There will be no political saviours. When it comes down to it, there shouldn’t be.

Looking at the West today, it is easy to discern the threats our own progressivism poses: The redefining of history (from the 1619 Project to the statue-bashing to inconvenient facts being sent down the memory-hole) and the battle over what should be taught. The woke would have us believe that Western civilization and the American Project were—and are—poisonous, built as they were on the backs and the blood of minorities. It is not just that evils have been done—which is indisputable—but that the very conception and essence of this civilization and republic are evil. The only solution to that is the one posed by the Soviets and their Communist comrades elsewhere: Tear it all down, rebuild, and reconstruct and retell history. After a generation or two, nobody will know any different.

The stories Dreher recounts of torture in Communist prisons are blood-curdling, and I was reminded of my tour through Hungary’s House of Terror, with its blood-stained cells and faint aura of stale misery that even many sterile cleanings could not remove. So many of these stories have been forgotten, especially as Marxism’s comeback makes this history particularly inconvenient. He quotes the famous Romanian pastor Richard Wurmbrand, who suffered horribly at the hands of his persecutors: “I speak for a suffering country and for a suffering church and for the heroes and the saints of the twentieth century; we have had such saints in our prisons to which I did not dare to lift my eyes.”

It bears mentioning that throughout all of this, the West did little to defend persecuted Christians. A few years ago, one of my older friends told me that he heard Wurmbrand speak shortly after he was freed and came to the US, around 1965. “I still remember at the end of his talk a reporter asked him about his appreciation to President Johnson for helping secure his release from Rumanian prison,” he told me. “Wurmbrand shook his head and with both hands flat on the table — he raised one finger and said: ‘This is what he did to get me released.’ Then he raised his whole hand and said: ‘Imagine who could be here today if he raised his whole hand.’”

In essence, Christians under Communism were forced to live in defiance of almost everything around them—the public education system, the universities, the entertainment, the press, the government itself. Their answer to all of this was to turn their families and their underground communities and their house churches into radical counter-culture cells within the culture at large. They memorized Scripture, prioritized family prayer, and kept the flame of faith alive in small shelters while the secular storm raged around them. Most of them believed that they would die under Communist rule, but many of them ended up being front and centre when the Velvet Revolution erupted and the Wall came down. In fact, one Christian who remembers those days told Dreher that things have gotten worse, spiritually speaking, since the end of Communism: “Christianity has become the secondary foundation in people’s lives, not the main foundation. Now it’s all about career, material success, and one’s standing in society.” Materialism is succeeding where Communism failed.

At this point, Dreher believes that the West will see a “soft totalitarianism” where Christians are increasingly forced to the margins of society by a series of inevitable choices that eject them from the mainstream (“you can be successful, or you can be faithful.”) He points to increasing pressure on medical professionals to give up their conscience rights as one example. “We’re going to either have to burn the pinch of incense or go find something else to do with our lives,” he told me. “This is something really revolutionary because I think many North Americans are accustomed to comfort and to being able to get exactly what we want without having to worry about it. But that’s over for serious Christians. Christians are going to have to ask themselves if they are willing to embrace the scorn of their peers and a loss of cultural status, a loss of social status, and the loss of entire professions open to us for the sake of being faithful.”

Considering the vitriol and anger with which Christians often react whenever a cultural commentator attacks one of their preferred comforts—think video games, or favorite TV shows, or films—it’s hard not to conclude that Dreher is right, as sad as it is. If Christians are unwilling to give up things that previous generations of Christians would have recoiled at, what happens when the time for real sacrifice arrives? To some extent, we are already seeing it: The rise of the “nones”—those who identify with no religion when polled—is not an indication of spiking secularization so much as casual Christians abandoning their previously preferred cultural identifier as it becomes inconvenient.

Dreher made no political predictions in his book, but when I asked him how he sees the next few years unfolding, he was ready with an answer. “I think the Democrats are going to win this fall,” he told me. “There is going to be a rush from the Left to pay back those who supported Trump, and also to pass legislation that locks in social advances that they see as socially progressive to try to keep people from coming back in and undoing them. And I think we may see a backlash from the Right at the next election in two years, and eventually it’s going to come to a point of blows. This is exactly what happened in the Spanish Civil War, from 1931 to 1935. There was such a ratcheting up between Left and Right in Spain’s new democracy that by the time you got to 1935, just before the outbreak of the war, people hated each other so much that they hated democracy because democracy was the way that the other side could come to power.”

“I think we’re going to go through a situation like that. Eventually what’s going to happen is there’ll be the institution of a social credit system [justified by a need for] social peace, social harmony, or tracking COVID. It’s going to be sold to us as something positive. But that’s going to be the way they get us. I would say this could happen within ten years. The technology is advancing rapidly. One of the Christian readers of my blog who works in tech sent me something from a tech journal talking about getting ready for the social credit system, trying to help tech companies prepare to make money from this coming to the U.S. We’ve already been accustomed to be surveilled all the time.”

Christians need to be ready for what comes. “This is ultimately going to result in persecution,” Dreher told me. “I say that not to be despairing, but simply to say that we’ve got to be clear about what’s coming and prepare ourselves for it. In Live Not By Lies, I tell the story about the Bender family and other dissidents coming together in their apartments or wherever they could for lectures and readings to tell the stories that were not being told in the Communist schools and in the Communist propaganda media. I interviewed Sir Roger Scruton in the last summer of his life. He received me at his farm, and he said that this is what those people had to do so they could remember who they were. If we lose cultural memory, if we don’t remember the things about who our ancestors were and the traditions we’ve been given, the Scriptural stories, all those things that make up the identity of a culture and its people—we become putty in the hands of the controllers. And that’s what they’re counting on. That’s what so much of this historical revisionism in American history is about—controlling the cultural memory of a people.”

“If we’re sitting back passively as Christians and allowing our enemies to define who we are in the minds of our own children, then we ought to be ashamed of ourselves.” It reminded me of a joke Michael Malice often tells: “Conservatism is just progressivism driving the speed limit.” If our children go to public schools, watch the same films, listen to the same music, and absorb the same ideology as everyone else, then we have already turned over the keys to the future. We simply prefer the gradualism of the slowly boiling frog to avoid becoming alarmed.

Those seeking a political solution to the current cultural crisis will find nothing in Live Not By Lies to give them comfort. Dreher sees Trump as a welcome pause in progressivism’s long, victorious march, and the judicial firewall he has helped shore up will be needed in the days ahead. But at the end of the day, this is about families, communities, and individual souls. Dreher’s thesis, essentially, is that Christians need to remember what Christianity is about—that there is no safety on Earth. Live Not By Lies often reads less like a cultural critique and more like a sermon. Only in Christ is there safety, and our material comforts have distracted us from this fact to our detriment. Thus, the trials ahead may not be bad if spiritual life is more important than material comforts. Chemotherapy is painful but healing. If we are deprived of the things distracting us from what is most important, perhaps we will turn our attention to the things that mattered to begin with: Faith and family.

***

Listen to my conversation with Rod Dreher about Live Not By Lies:

And here’s my previous conversation with Dreher about The Benedict Option, for anyone interested: