Blog Post

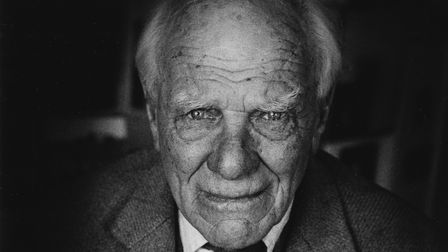

Malcolm Muggeridge on Christ and the Media

By Jonathon Van Maren

In his slim 1977 volume Christ and the Media, Malcolm Muggeridge describes a scene instantly recognizable to anyone familiar with political protest in our TV age. He was in Washington, D.C. working as a correspondent and came across a group of protestors moping about, holding slackened signs, chatting. Bored police were also present. What were they waiting for? The cameras, as it turned out. Once they showed up—action! “Whereupon placards were lifted, slogans shouted, fists clenched; a few demonstrators were arrested and pitched into the police van, and a few cops kicked until, ‘Cut!’” Moments later, the streets were again silent. On TV that evening, it all looked very impressive. “On the television screen,” revolutionary Jerry Rubin once observed, “news is not so much reported as created.”

Christ and the Media contains a series of lectures Muggeridge delivered on the growing power of the media and its ability to reshape society in its own image. Muggeridge’s own experience with TV—as a documentarian, renowned interviewer, and regular fixture on the BBC—gave him insights into the way in which the medium creates a fantasy that frequently bears little resemblance to reality, but increasingly transforms it. This is true for the feedback loop between activists and the media—I’ve written about the ways the press deliberately slants coverage and utilizes outright deceit to portray abortion activists in a positive light—but it is also true due to the way information is conveyed through images, which often conceals while pretending to reveal.

Muggeridge was an absolutist when it came to TV, and his own many famous appearances notwithstanding, refused to permit one in his home. Television, he asserted, creates fantasy and distorts reality and thus should be rejected. He pointed out, for example, that culture would inevitably be corrupted by the medium due to the difficulty of rendering the cardinal virtues through imagery and the relative ease of celebrating vice. He quotes Simone Weil’s insight to make his point: “Nothing is so beautiful, nothing is so continually fresh and surprising, so full of sweet and perpetual ecstasy, as the good; no desert is so dreary, monotonous, and boring as evil. But with fantasy it’s the other way round. Fictional good is boring and flat, while fictional evil is varied, intriguing, attractive, and full of charm.”

Muggeridge saw this corruption coming long before it metastasized, and he knew that it would. He asserted during his lectures that there would come a time when Christians would be forced to disassociate with TV due to pervasive carnality, blasphemy, and the glorification of other sins. I wonder what he would say if he could see many prominent Christian critics celebrating shows such as Game of Thrones—and those who condemn these shows blasted as Puritans (a term, incidentally, used pejoratively rather than positively) and legalists, with all the ferocity of Gollum defending the ring. Christians in the 21st century are willing to defend and celebrate entertainment (which C.S. Lewis called “the Devil’s substitute for joy”) that would have incensed and appalled every previous generation of Christians.

Muggeridge actually anticipated the argument that we could consume corrupt entertainment without corruption and laughed it off with contempt. Advertisements, he noted, are designed to stoke greed and envy and make people foolish—an African witch doctor visiting the enlightened West would grow green with envy at the ability of snake oil salesmen on the tube to flog their wares to credulous audiences. It is thus nonsense to claim we will not be impacted by the entertainment we consume:

[I]t would seem clear to me that, if edifying scenes on television uplift the viewers, it must also be true that unedifying scenes degrade them. Furthermore, when very large sums of money are paid for advertising at peak viewing periods, as they are, it can only be because the often quite ridiculously unconvincing advertisements shown in such expensively-purchased time do have sufficient drawing power to justify the expenditure. Every performer knows that television appearances have an impact, for good or ill. How can it possibly be doubted, then, that spectacles of carnality and violence likewise affect the viewer?

Muggeridge also prophesied that the sheer volume of media directed at us would render us stupider rather than more enlightened, as we became glutted on information rather than truth. He quotes Paul quoting Isaiah: “Hearing, ye shall hear and shall not understand, and seeing, ye shall see and not perceive, for the heart of these people is waxed gross and their years are dull of hearing and their eyes have they closed, lest they should see with their eyes, and hear with their ears, and understand it with their hearts.” In 1977, the average adult spent eight years of his life watching TV; today, with media coming at us from every screen, the number of screen-hours dwarfs that.

I wonder what Muggeridge would say now about the digital conservative media landscape, which I contribute to in a small way with podcasts, as well. Muggeridge could not have known that the public square he prized so highly would eventually become, in real and important ways, a digital one—and that in a media landscape with no alternatives, the progressives he spent a career dismantling would reign supreme. I have found his own TV interviews to be highly rewarding viewing (his conversations with William F. Buckley are fascinating); he responded to one questioner who alleged hypocrisy by his refusal to have TV while appearing frequently on it by saying that “as a television performer, I see myself as a man playing piano in a brothel, who includes ‘Abide with Me’ in his repertoire in the hope of thereby edifying both clients and inmates.” Rhetorically perfect; practically unsatisfying.

Christ and the Media is worthwhile precisely because it forces the reader to grapple with inconvenient truths. Regardless of how much one enjoys various media outlets—as I certainly do—it is hard to argue with Muggeridge’s analysis, and his conclusion is a sobering and unavoidable one: “The media have, indeed, provided the Devil with perhaps the greatest opportunity accorded him since Adam and Eve were turned out of the Garden of Eden.” At the very least, we must approach media consumption with extreme caution and a level of discernment that we generally prefer to avoid—and this goes for right-wing media as much as mainstream media. Our non-stop consumption of highly produced information has not made us happier or better informed. We have more facts, but less perspective. Determining the truth is frequently more difficult than ever.

Which is why, Muggeridge states, we should not let the media clamor distract us from the most important things. I know that I do. If you find the same thing happening in your life, Muggeridge’s brilliantly-written book may offer you a helpful reality check and a prompt to re-examine the differences between fantasy and reality—and why they matter.

I liked Muggeridges’ thoughts. We raised our 6 children without TV, but it seems a dystopian Culture has barged in on some of them!

A dystopian Satanic culture is out to allure them……every day….. but we pray!

If TV set this guy off, just think what social media would do to his brain.

Nothing worse than social media has done to ours, I’ll bet.