Blog Post

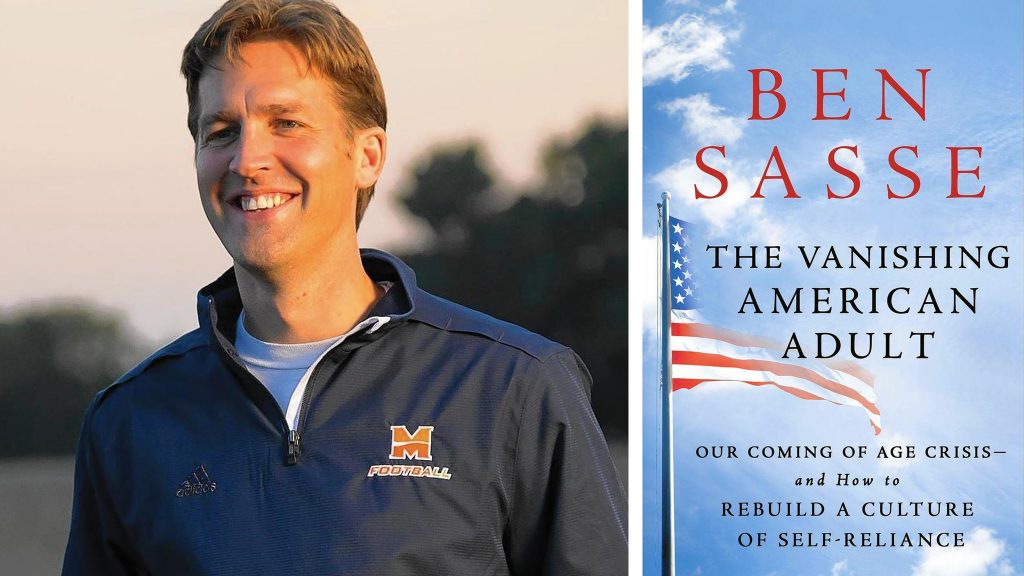

The Vanishing American Adult

By Jonathon Van Maren

Ben Sasse is no ordinary senator. Born in Plainview, Nebraska, he subsequently earned a doctorate in American history from Yale, served as an Assistant Secretary in the U.S. Department of Health, taught at the University of Texas, and served as president of Midland University in Fremont, Nebraska before successfully running to represent his state in the U.S. Senate in 2014, and was sworn in on January 6, 2015. Amid all of his senatorial duties and the chaos of Washington D.C., he also found the time to write a book.

The Vanishing American Adult: Our Coming-of-Age Crisis and How to Rebuild a Culture of Self-Reliance is Sasse’s attempt to diagnose the disintegration of culture step-by-step and offer practical (and often personal) responses. The upcoming generations of Americans, he notes, stand alone in American history in their prolonged adolescence, compulsive consumerism, and lack of literacy. Social media makes them slaves to the here and now, and unprecedented luxury has disconnected them from any understanding of the suffering that characterized human existence for thousands of years. Self-reliance has been lost, and for America to survive, it must be regained.

One of his primary pieces of advice is simple: Embrace work pain. Too many young people, writes Sasse, have never actually had to do hard, physical labor, the type of work that helps you learn how to “suffer.” It may seem hard to believe, but many people have never actually experienced the sort of work that makes their muscles ache and their entire body hurt the following morning. It is for this reason that Sasse sent his 16-year-old daughter off to a ranch to learn how to work, and ended up tweeting the texts he got from her doing various ranch tasks—texts that went viral and had parents messaging Sasse asking how they could do something similar with their own kids. It is important, Sasse writes, to experience what he calls “real life”—like watching an animal give birth, for example.

Sasse’s practical suggestion is that parents should make their kids do chores. I’m pretty sure this is why my dad got a little shed with an assortment of random animals; pygmy goats, pigeons, chickens, geese, and ducks, to name a few. Each morning, from the age of 6 or 7, I’d get up early before the school bus arrived to to lug buckets of water and grain to the shed to feed the animals (who were still fast asleep). I think the first time I saw an animal give birth was our goat Marigold, or maybe calving at the family farm my uncle and grandfather ran together. I found it genuinely interesting to read that experiences that were just part of growing up for me (and nearly everyone else in the rural community where we lived) are increasingly rare today.

One of Sasse’s key emphases is something we should all pay a little closer attention to: Consume less. Because we are generally insulated from necessity, he writes, we have begun to treat luxuries (like the latest technology, or video games, or smartphones) as necessities. We must recapture two essential traits that all previous generations were intimately familiar with: Deferred gratification and self-denial. Today’s consumer culture with an 24-7 economy that actively attempts to stoke greed and envy to sell products is creating dissatisfaction, unhappiness, and entitlement. It is time, writes Sasse, that we work to understand the difference between needs and wants.

Our culture attempts to sell us the idea that things can make us happy, but Arthur Brooks of the American Enterprise Institute has noted that happiness is generally determined by four factors (and you’ll notice that none of them are things): Faith, or a framework for death and suffering; Family, a good home life; Work, a job that you feel is a calling and is worthwhile; and community—having at least two real friends who feel share your joy and suffering. The political scientist Charles Murray, author of Coming Apart: The State of White America, concurs: All of the studies indicate that things don’t make us happy, which explains why people are blowing their brains out in front of wide-screen TVs.

This is particularly concerning when you consider a series of alarming new studies that indicate that Millenials and Generation Z are addicted to consumerism in a way that previous generations were not. Today’s youth often do not understand what penny-pinching is (Sasse’s stories of his grandparents’ experiences during the Great Depression reminded me of the glass ashtray I received after my maternal grandfather passed away, the first birthday gift my grandmother bought him after they immigrated from the Netherland by painstakingly saving her pennies week by week.) What we have today, Sasse points out, was outside the reach of most kings a few short centuries ago.

Nostalgia should not make us forget that for most of human history, life was simply about survival, and survival was no sure thing. One writer noted that “all historians give us are oases in the sands of time, and we linger fondly in these, forgetting the vast tracks between that are trodden by the weary generations of men.” Life was often nasty, brutish, and short. Sasse tracks the devastating changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution and the accompanying collapse of an agricultural economy, and our subsequent move into the commerce culture that we now inhabit. It is key to remember that we have privileges today that would have been unfathomable even a century ago. It is also important to remember, writes Sasse, that all of the philosophers agreed that it is very difficult for a republic to be both rich and virtuous.

One way to remind ourselves of our privilege as Westerners, Sasse notes in Chapter 7, is to “travel to see.” Going to nations where people live in poverty or are simply far less wealthy provides a much-needed sense of contrast. That was certainly true for me, although I’ve never mentioned it in writing since it is so cliché: When I did a week-long trip to Mexico years ago, building houses atop a garbage dump near Agua Prieta, I got a good idea for the first time just how blessed I was back home. The “houses” we built were a concrete slab, tin walls, and a tin roof, perched atop a landfill that gave up its rancid treasures each time it rained. Sights like that have the ability to make you profoundly ashamed of all your complaining when you realize that entire families live in flimsy structures smaller than your bedroom.

Sasse also objects to what he calls “collecting places”: Too many people engage in tourism rather than real traveling. You don’t get to have real experiences snapping a quick series of selfies in front of immediately recognizable landmarks, he writes, and young people should actually take the time to explore different places. I know what he means: On one of the first trips I took to Europe, I blitzed through Germany without really taking the time to soak it in, snapping photos at Checkpoint Charlie, the Brandenburg Gate, the Reichstag, and virtually nothing else (although I did take the time to hunt down the lonely parking lot between a few giant apartment complexes where Hitler’s corpse was burned after he shot himself.)

Travel, says Sasse, helps you to be alone, helps you to understand things, overcome prejudices, set priorities, sleep anywhere, and forgo luxuries. You should do your homework before leaving home to get the most out of it. He’s right. Some of my most vivid memories are from travels where I ended up wandering: through sweltering Cairo streets at 3 AM, when all the bazaars are still open; a kibbutz in Israel; the Appian Way outside Rome, where thousands were crucified after the Spartacus rebellion; the cobble-stoned streets of Boston, where Paul Revere’s house is buried within a maze of alleyways in the North End. Some places have not yet been ruined by kitschy carpetbaggers, like Tombstone and the OK Corral in Arizona (the Town Too Tough Too Die!) Travelling done right forces both introspection and self-awareness, because it forces you out of familiar surroundings.

Beyond hard work and traveling, Sasse writes, it is also important for families and individuals to “Build a Bookshelf.” Becoming literate, he notes, is a choice, and we cannot claim our true inheritance as Americans—or Westerners—with ignorance. The good news is that no generation in all of human history has had access to cheap books the way this one does. (Anthony Esolen calls the accessibility of the great canon of Western civilization “unused artillery.”) Sasse details the literacy levels that once existed, and how TV gradually replaced newspapers as the public’s main source of information. Then, of course, TV became entertainment, and by 2010 newspaper circulation was down to 15% of the population.

Accompanying these changes was the decision of universities to do away with the foundational books of Western civilization as a common core of classics between the 1960s and 1990s. Without this canon—which Allan Bloom so famously warned would result in people unwittingly caving to the idea that the here and now is all there is—we no longer speak the same language. Sasse points to the example of Lincoln, who spent less than a year in school, but illustrated with every speech he gave how deeply he was steeped in the Western canon as well as the fact that he expected his audience to recognize his references. That would no longer be true today. I suspect the language of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address would be unrecognizable to most of the current generation of Americans.

Sasse suggests that each person develop their own canon to facilitate literacy. His own choices are a testament to his Reformed background, with Luther’s Commentary on Galatians and Bondage of the Will, Augustine’s Confessions, and Calvin’s Institutes being primary picks. Some classic history like Thucydides is important, and Chaucer and Shakespeare are, of course, essential as well. I was familiar with nearly all of his list except for his choices in economics, where my reading has been woefully inadequate. (I attempted to take some economics in university, but my first professor was a fellow named Krishna Pendakur who showed up in flip-flops, a tie-dyed T-shirt, and an enthusiasm for socialism. That killed my interest pretty effectively.)

Sasse closes The Vanishing American Adult with a chapter entitled “Make America an Idea Again.” It’ll be a tough road, he writes, but America’s best days could be ahead of her (an assertion that you will probably find dubious upon reaching the end of the book.) Despite his optimism, Sasse notes three of his primary concerns for the coming years: Accelerating technologies wiping out many of our current jobs; the coming-of-age crisis detailed throughout the book that is rendering a generation incapable of dealing with this crisis; and the rise of people who take advantage of times of disruption to offer quick fixes, nativist campaigns, and more centralized power as solutions. Additionally, the threats to the First Amendment posed by the Left must be repelled.

Ben Sasse’s offering is one of the most comprehensive analyses of cultural breakdown combined with workable solutions to come out in recent years. Sasse’s writing is compelling and readable, his ability to synthesize and summarize is impressive, and his ability to offer tangible solutions sets his work apart from many of the other doomsday tomes that populate bookstores these days. I heartily recommend it to anyone interested in grappling with these issues.

_________________________________________________

For anyone interested, my book on The Culture War, which analyzes the journey our culture has taken from the way it was to the way it is and examines the Sexual Revolution, hook-up culture, the rise of the porn plague, abortion, commodity culture, euthanasia, and the gay rights movement, is available for sale here.