Blog Post

Why progressives hate one of European history’s greatest naval heroes

By Jonathon Van Maren

After a morning speaking on pro-life apologetics to students at the Hoornbeeck College in Goes, I headed with a friend to visit the town of Vlissingen in the Dutch province of Zeeland, a village of seafaring people that hugs the coast of the North Sea. Fog was billowing in from the water, and as we walked along the rows of shops and terraces that are packed with tourists come summertime, it was difficult to make out the landmarks as we walked towards where the point juts into the sea. There was a statue of a severe-looking woman wearing a bonnet, a long dress, and an expression of resignation, gazing out over the water, a representative of all those wives and mothers who have seen their men vanish into fog just like this and slip from their grasp forever. There were Napoleonic era cannons, mouths gaping silently seaward. And then, finally, the man I had been looking for: Michael de Ruyter.

He stood on a pedestal high above his North Sea, his gaze pointed downwards, a sacrilegious seagull perched impertinently on his head. The streaks of white in his black locks indicated that the great admiral was a popular resting place for seafaring birds, and perhaps it is only fit. The humble man certainly would not have minded. Other than that, he was dressed impeccably: High boots, long jacket, a sash, a cape draped over his arm. In one hand he carried a scroll, and on the base of the pedestal a plaque with the reliefs of several beleaguered galley slaves freed by De Ruyter, chains still fastened to their ankles and hands still clutching their oars, reach out to his disembodied outstretched hand in gratitude. On either side of him, cannons retrieved from the wreck of his ship have flanked him since 1905. Another plaque notes the great man’s donations to the poor people of Vlissingen, who he never forgot even after he reached the pinnacle of naval power. But perhaps I should start at the beginning.

Michael De Ruyter was born the fourth of eleven children on March 24, 1607, and it was said that he felt the sea “quickening in his blood” even as a boy, and his father, the beer porter Adriaan Michielszoon, despaired at his son’s refusal to dedicate himself to his schooling. As a child, one story goes, he actually scaled the tower of St. Jacob’s Church (where he was baptized and would later be married.) Despite numerous restorations, the Church still towers above the town, and I squinted at the steeple above the clock, shrouded in the mist. De Ruyter had apparently been trapped on the steeple when labourers unwittingly removed the ladders he had used in his ascent. To get down, young De Ruyter was forced to pry tiles off the church roof and drop into the building.

So it was no wonder that De Ruyter’s father decided to pull him out of school and send him to work as an apprentice rope-maker with shipowner Cornelius Lampsins at the age of only eleven years old. Part of the building that hosts the Vlissingen Maritime Muzeeum (the awkward spelling a play on Zeeland) today is actually the old Lampsinhuise where De Ruyter once worked. The Lampsins were a phenomenally wealthy Dutch merchant family, and Cornelius (1600-1664), actually served as the Baron of Tobago with his brother Adrian from 1662 to 1664 and was heavily involved in the colonization of the Caribbean throughout the 1630s. One room features beautiful oil paintings of the various Lampsin scions: Cornelius cuts an impressive figure, a paunchy, solemn, middle-aged man with shoulder-length black hair, a black mustache, and a cross hanging around his neck. He is surrounded by the solemn faces of his relatives.

Next to him hangs Apollonius Lampsins (1674-1728), the Governor of the Dutch East India company and the mayor of nearby Middelburg—his head is sprouting an enormous, ash-gray wig, his mouth is pursed in a manner that is hard to read, and the artist has paid meticulous attention to his double-chin. It is the face of a man who was born to riches. The portrait of the porcelain but enchanting Constantia Lampsins is so real she appears to be looking back at you, with her black curls wisping towards her large hazel eyes. The label on her portrait says she died young—at only 27 years old—but I can’t find any information about her other than that. There are others, as well, including some full-length portraits of chubby, serious-looking children. The existence of these portraits alone indicates the fabulous wealth of the Lampsins, and it was this family that first hired De Ruyter and sent him where he always longed to be: Out to sea. He started off as a cabin boy, and would soar to the pinnacle of naval power.

By the age of fifteen De Ruyter had already risen to the rank of petty officer, and as a young teen De Ruyter briefly fought as a deck gunner against the Spanish in the Eighty Years’ War, joining the Dutch forces under the brilliant Maurice of Nassau, son of William of Orange. His whaling ship was conscripted to help break the 1622 Siege of Bergen-op-Zoom against the Spaniards, and several weeks later his ship was captured by Spanish privateers and De Ruyter’ face was slashed by flying shrapnel before he was taken prisoner. In exceptional feat, he escaped the pirates, swam to shore, and then managed to cross Spain, hike across the Pyrenees, wind his way through France, and eventually arrived safe back in the Netherlands. His exploits did not go unnoticed by the Lampsins, who promptly promoted him and sent him back out to sea aboard one of their ships.

Although Dutch sources say very little about De Ruyter’s life between his time fighting the Spanish and his marriage on March 16, 1631 to the farmer’s daughter Maayke Velders, some English sources place him in Dublin from 1623 on, acting as an agent for the Lampsins’ merchant house. He was known to speak Irish Gaelic fluently, and also sailed through the Mediterranean or up the Barbary Coast, occasionally acting as a privateer on the Lampsins ship Den Graeuwen Heynst. But we know for certain that when De Ruyter’s wife Maayke died giving birth to their daughter in December of 1631 and was followed into the grave by the little girl three weeks later, the 24-year-old De Ruyter was devastated. Alone once again, he returned to the sea.

For a while, De Ruyter worked as a whaler, serving as the navigating officer of the Green Lion and running expeditions to the Norwegian Arctic island of Jan Mayen in 1633 and 1635. In 1636, five years after Maayke’s death, he married Neeltje Engels, the daughter of a well-to-do burgher who bore him five children, four of whom survived. Adriaen was born in 1637, Neeltje in 1639 and Aelken in 1642. A second son, Engel, came along in 1649. There are no existing portraits of Neeltje, so we unfortunately have no idea what she looked like. Early during this same period, from 1637 to 1640, De Ruyter finally achieved the position of captain, and for three years he hunted pirates operating out of Dunkirk and threatening Dutch merchant ships. In once famous incident, De Ruyter greased the deck of his ship with rotten butter that had spoiled in the hold, outfitted his men in socks in order to ensure they would maintain their grip, and waited for the pirates to board. When they poured over the side, they promptly began to slip, scrabbling wildly at the deck. De Ruyter’s men then emerged from hiding, and the buccaneers were captured or pushed back overboard in short order.

By then a renowned seaman, De Ruyter accepted an offer from the Zeeland Admiralty to become captain of the Haze under Admiral Gijsels, fighting against the Spanish in an alliance with the Portuguese. The Haze was a man-of-war with 26 guns, and as third-in-command, De Ruyter forced a fleet of Spaniards and Dunkirkers to retreat in a sea battle off the coast of Cape St. Vincent on November 4, 1641. Following the victory, he promptly returned to life as a merchant sailor, finally purchasing his own ship the Salamander and traveling throughout Morocco and the West Indies. His reputation grew—he was known as a pious man and was much beloved by his men. He became renowned among Dutch sea captains as a godly sailor who regularly used his own wealth to free Christian slaves by purchasing or ransoming them, a fact that makes the recent slanders of De Ruyter particularly insidious. In 1650, tragedy struck again: Neeltje died. At the age of forty-three and with three young children, De Ruyter was a widower for the second time. Two years later, he married the widow Anna van Gelder, purchased a house in Vlissingen, and decided that it was time to leave the sea and dedicate himself to family life. His hard-earned retirement would last only seven months.

Two years later, the First Anglo-Dutch War exploded. A war fought entirely at sea, the Dutch had grown increasingly furious over English attacks on Dutch merchant ships, and De Rutyer was offered a position on a fleet of warships serving under Maarten Tromp. He refused the position, but the pressure continued and eventually he buckled. His brilliance as a sea commander soon became apparent, with victories at the Battle of Plymouth, the Battle of Kentish Knock, the Battle of Gabbard, and the Battle of Scheveningen, which ended the war but cost Tromp his life. De Ruyter was offered command of the fleet, and again after an initial refusal, agreed to become the Vice-Admiral of the city of Amsterdam on March 2, 1654. In 1655, De Ruyter moved his family from Vlissingen to Amsterdam. Years of relative peace followed, with the exception of a handful of military interventions and skirmishes with pirates. At one point, De Ruyter actually created a special troop of soldiers equipped and trained to attack enemy positions from the sea. He called them Sea Soldiers, and this was the first time this military tactic had been employed in the Modern Era. They would become known as the first marines.

But in 1665 the Second Anglo-Dutch War began with Charles II sending privateers to sink Dutch ships, destroy Dutch trade, and capture the colony of New Amsterdam (which was then promptly renamed New York.) In response, De Ruyter led his fleet of thirteen ships into Carlisle Bay near Barbados, hammered the English batteries with cannon fire, and wrecked many of the ships harbored there before retreating to repair the damage to his own ships. Sailing north and capturing several English ships along the way, De Ruyter actually briefly captured St. John’s, Newfoundland before returning to the Netherlands, where Johan de Witt, one of the most powerful leaders of the Dutch Republic, appointed him the commander of the entire Dutch fleet on August 11, 1665. To the Dutch people, De Ruyter was a home-coming hero. To his men, he was “Bestevaêr,” or “grandfather,” a term of affection bestowed on him due to his refusal to pay attention to hierarchy, a habit stemming from his own humble origins. In June of 1666, De Ruyter obtained victory in the Four Days Battle and fired Cornelis Tromp (Maarten’s son) after a near-disaster during the St. James’s Day Battle two months later.

De Ruyter recovered from a serious illness in time to take command before the infamous Raid on Medway in 1667, where De Ruyter sailed up the Thames River with 62 warships, 12 fire-boats, and 15 sloops-of-war, burning naval bases, torching seaside towns, and setting nearly the entire English naval fleet ablaze before sailing off with the king’s flagship, HMS Royal Charles, in tow. The symbolism of the Dutch capturing his flagship was politically devastating for King Charles, and the war was swiftly brought to an end with the Peace of Breda, which was enormously favorable to the Dutch. The Raid on Medway is still considered to be one of the worst humiliations in the history of the British Royal Navy and the British military, and is certainly the worst defeat ever suffered by the British in their own waters. Over two centuries later, Rudyard Kipling would commemorate the event in a scathing poem titled The Dutch in Medway:

No King will heed our warnings,

No Court will pay our claims—

Our King and Court for their disport

Do sell the very Thames!

For, now De Ruyter’s topsails

Off naked Chatham show,

We dare not meet him with our fleet—

And this the Dutchmen know!

As a result of these victories, De Ruyter’s stock soared so high that Johan De Witt forbade the commander to go to sea, fearing that he might be killed—although ironically, in 1669 a supporter of the sacked Cornelis Tromp incompetently attempted to murder him with a breadknife in the foyer of his own house.

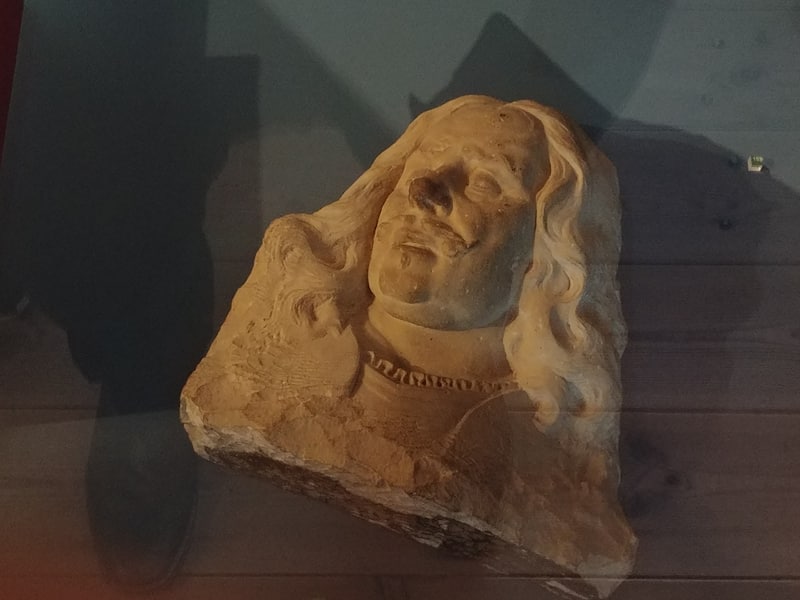

The Third Anglo-Dutch War, in which he faced off against the English allied with the French, would be De Ruyter’s last. In nearly every naval battle, he achieved victory against all odds and against much larger fleets, including at the Battle of Solebay in 1672, the Battle of Schooneveld in 1673 and the Battle of Texel that same year. The brilliance and courage of his naval tactics stunned his enemies, who soon began to accord him unprecedented respect. In February, a new title was created specifically for De Ruyter: Lieutenant-Admiral General. (At one point, the French admiral Abraham Duquesne informed King Louis XIV in a report that, “The Dutch fleet under De Ruyter can enter a moonless night in heavy wind and fog and emerge the next day in a perfect line ahead.”) In 1676, De Ruyter engaged the French fleet in the Mediterranean. A French cannon ball tore off his leg, and when the French commander heard that De Ruyter had been wounded, he immediately called off the assault. Such was his respect for the Dutchman that he sent his two best ships to escort De Ruyter’s vessel back to the Netherlands, and King Louis XIV ordered every French battleship to fire a salute as De Ruyter made his final journey home. He died of gangrene along the way. On the top floor of the Vlissingen Muzeeum, De Ruyter’s death mask rests in a glass case. His mouth is slightly open, and his eyes appear to be as well. Although he is at peace, his face still appears worried, as if the burden of his nation still rests on his shoulders.

De Ruyter is not only a hero to the Dutch, although many give him credit for being the historical figure most responsible for ensuring the continued survival of the Netherlands as an independent republic. He is also a hero to the Reformed Christians of Hungary as a result of his actions early in 1676, just before he was killed. A group of Hungarian preachers were imprisoned on board Spanish galleons as rowing slaves for refusing to recant their Calvinist faith—their number had dwindled from 350 to 26 by the time De Ruyter arrived to free them from the ships in Naples. In the Muzeeum, there is a painting of De Ruyter, his long hair turning white, standing on the deck of his ship. Shirtless, emaciated men with unkempt beards are kneeling before him, clutching at his hands, their faces stricken with gratitude. De Ruyter was buried in the New Church in Amsterdam during an elaborate state funeral on March 18, 1677, and when I visited his crypt in 2017 on a trip to the Netherlands for the March for Life, there were wreaths lying atop his casket, placed there by Hungarian Christians who have not forgotten De Ruyter’s deeds all these centuries later.

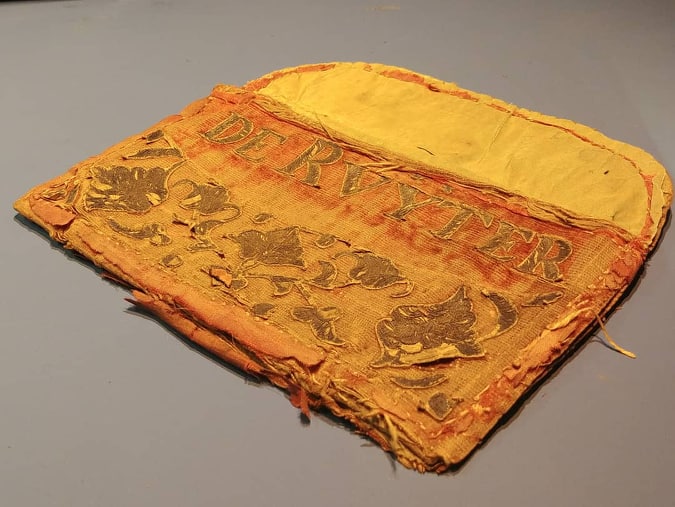

The Vlissingen Maritime Muzeeum does an excellent job of bearing witness to the life of this great man, with glass display cases filled with the flotsam and jetsam of the noble seaman’s life. There was his seal, alongside a red cloth pouch with the name De Ruyter stitched across it that once held the letters he regularly wrote to his wife. There is a 1660 portrait of his last wife, Anna Velders, wearing a black bonnet and pearl earrings, her eyes soulful beneath dark black eyebrows. There are portraits of him, too, some of them painted during his lifetime: Wearing civilian clothes and a serious expression, wearing armour and a determined expression, in full naval regalia, his face tight with determination. There are a few things that have been excavated from his ship, too, as well as the white nightgown he died in. Another display case is loaded with the evidence that De Ruyter has achieved an unshakeable—and perhaps unmatchable—position in the pantheon of Dutch heroes: Pop bottles sporting his face, De Ruyter toys, De Ruyter medallions, De Ruyter games. He lived well, he died nobly, and he loved his God, his family, and his country. It is no wonder that this solid, stocky man still looms large in the national imagination.

It is for these reasons that a handful of Dutch left-wingers have attempted to scrabble pathetically around the base of his pedestal, insisting that De Ruyter was a “colonialist” and that he should thus be charged with the sins of the slave trade, regardless of the fact that he had no association with it, never had slaves on board, and freed slaves at his own expense. Even the Muzeeum does an admirable job of dismissing these ahistorical charges out-of-hand, but I noticed upon visiting his crypt that his detractors have managed to get a plaque put in front of his grave that adds this little line to a list of his accomplishments: “Nowadays his name is increasingly linked to the debate on the Republic’s slave trade.” Of course, it is only linked to the slave trade by them, and they are only doing so because De Ruyter is the sort of man that progressives today, with their glorification of vice and the derisive denial of masculinity, cannot understand. Worse, they know that De Ruyter would be profoundly ashamed of them.

It reminds me of something Hilaire Belloc once wrote about the iconoclastic progressive, most notably that he hopes “that he can have his cake and eat it too. He will consume what civilization has slowly produced over generations of selection and effort, but he [has no] comprehension of the virtue that has brought them into being. Discipline seems to him irrational, on which account he is ever marveling that civilization, should have offended him with priests and soldiers…In a word, the Barbarian is discoverable everywhere in this, that he cannot make: that he can befog and destroy but he cannot sustain; and of every Barbarian in decline or peril of every civilization exactly that has been true. We sit by and watch the Barbarian. We tolerate him in the long stretches of peace, we are not afraid. We are tickled by his irreverence; his comic inversion of our old certitudes and our fixed creed refreshes us; we laugh. But as we laugh we are watched by large and awful faces from beyond, and on these faces there are no smiles.”

Great article, you have a gift with words

Thank you!

It always amazes me how nations will eradicate history and replace it with their own nationalistic perspective. Historical facts need to be looked at from more than one country’s perspective. The losers negate to mention factual events. For instance, the Raid on Medway the English thought could never happen since they had spanned the entrance with a heavy chain preventing vessels to sail up the passage which De Ruyter smashed through with his leading ship. Thank you for highlighting the profound faith of this truly God-fearing man. May we follow his example in our homes, families and apply this trust and faith in the hope we have in our risen Savior who was also a living example for Michiel De Ruyter.

Great article , I am all Dutch, and we see the slandering throughout history by those that seem to have the most powerful voice of the time.

Just as we see the pro life / pro abortion debate happening today, and I will not say pro choice.

I got to see you in Chatham at the pro life dinner with some youth, and you did a Great job articulating the 3 keys of hope, and I agree, as I have been bringing youth to Ottawa for the last 12 years or so to the National March and see these youth as more informed on what Abortion actually is and believe it will bring change in the next generation or so.

Keep up the good Work Jonathan and will maybe see you in Ottawa if your their with our Group