Blog Post

How the elites will take revenge on Middle America for electing Donald Trump

By Jonathon Van Maren

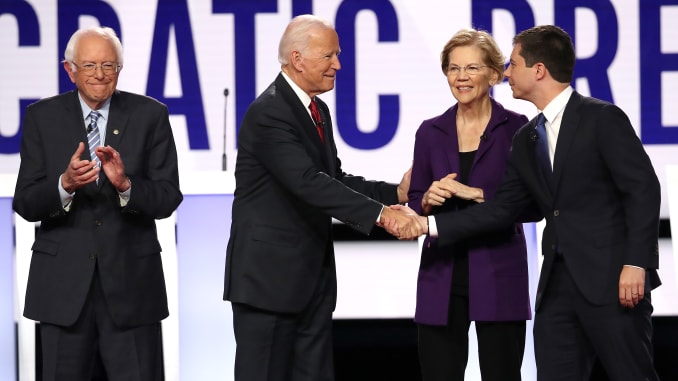

Justin Webb, the presenter for Radio 4’s Today programme (and previous North America editor for the BBC), has written a chilling analysis of what America’s future could be like post-Trump over at Unherd titled “America’s Elite is Plotting Revenge.” Keep in mind, as you read this, that many of the policies he suggests the Democrats might pursue have already been put forward by top-tier candidates (Pete Buttigieg, for example, has already proposed expanding the U.S. Supreme Court, primarily to protect legal abortion. If you can’t win the game, change the rules.) Consider this excerpt:

Donald Trump might not be able to place Kansas City on a map, but the America he has adopted — NASCAR America — looks capable of keeping up with the racing cars. Perhaps even catching them up. The President uses the language of the downtrodden. He shares their contempt for sociological inquiry, their love of guns. Their suspicion of folks who don’t come from these parts. He has used his presidency to play with the minds of the liberal elites. He looks likely to be re-elected and to have the right to double down on all of the above. A Trumpian wave is sweeping all before it.

But what if this is an illusion. What if the crisis facing modern America is not Donald Trump and the things he says and does, but the coming backlash against him? A backlash so colossal that it will destroy The Donald, his men, their towns, their social attitudes: the lot. And in doing so change America forever.

Take the Iowa caucus. Since the early 1970s, this state, with its small homogenous population, has had an outsized influence on the presidential race by dint of kicking the process off every four years. In my decade reporting on America for the BBC, I spent a considerable amount of time in Iowa. I remember nearly losing my toes to the cold during a forest trip with some locals who hunt deer with bows and arrows. Most Americans stay warm and away from longbows. But the Iowa caucus — and the New Hampshire primary that comes tomorrow — forces everyone to come and take a look at how life is lived in corners of the nation most people do not see…And now? Well, Iowa is finished.

Admittedly the disasters this year were caused not by the locals but by the apps designed by sophisticates to enforce rules demanded by Bernie Sanders supporters — but these are details lost on most Americans. The New York Daily News headline captured the mood: “Corn clogged Iowans Botch 1st Dem Vote.” A pile-on began. Soon it was pointed out that Iowans are mostly white; that the system of voting in a caucus (you have to turn up) reduces the rights of people who cannot make it; etc etc etc. Never mind that these white rubes chose Barack Hussein Obama as the Democratic candidate and backed him in the general elections of 2008 and 2012. The Democratic party modernisers have a plan for Iowa: stop going there.

Illinois Senator Dick Durban led the way: “I think the Democratic caucus in Iowa is a quirky, quaint tradition which should come to an end. As we try to make voting easier for people across America, the Iowa caucus is the most painful situation we currently face for voting.”

It won’t end with Iowa. It will gather pace now — either this year or, more likely, at the end of Trump in 2024 (or at his second and more successful impeachment), when Democrats could be elected to the presidency and both houses of Congress on a programme of sweeping change.

First: pack the supreme court with enough justices to turn the tide socially. Enshrine the social mores of San Francisco forever at the apex of American power. It would not be unconstitutional: the founders made no stipulation about numbers of justices on the court.

Second, get rid of the electoral college for presidential polls. No presidential candidate will ever again go to a small town. Because the election is split between states, candidates actually have to visit and spend money in those they think they can win. It’s good for business in the small ones. It gets them on the map every four years. Without the college, candidates could amass votes in New York and California and Florida and not bother about the rest of the country. LA hello, Boise cheerio. Job done.

Or half done. The biggest prize of all for the post-Trump-era zealots of the Left is the US Senate. Their argument will be simple. The Senate — with two members from each state, however small its population — is fundamentally undemocratic. By 2040, according to Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute, 70% of Americans will live in 15 states. Those states will contain almost all the big cities. The other 30% of Americans — in small towns and in wilderness cabins — will elect 70 Senators. 70! Out of 100! The Senate controls everything, remember — from impeachment trials to Supreme Court nominations. Rubes still in charge.

The point — and it’s a fair one — is that American cities and suburbs drive enterprise but do not control it. More than three quarters of all the venture capital being deployed in America goes to just three states, according to researchers at think tank The Economic Innovation Group. More than a third of the jobs in America’s most innovative industries — technology, computer manufacturing, biotech — can be found in just 16 counties, according to the Brookings Institution. There are more than 3,000 counties in the US — 31 of them account for two-thirds of the nation’s GDP.

Until Trump came along, there was a rough and ready sense that the two Americas — the expansive one where tumbleweed blows, and the compact one where engines hum and people live — were willing to co-exist, however much they might bicker. But the severity of the reminder that they are not in charge has changed the minds of the city dwellers. It has hardened their hearts. They will not — post Trump — have any qualms about getting that situation remedied.

And it will be remembered, with some bitterness, when this reckoning comes, that the rubes went overwhelmingly for Trump. As David Wasserman of the non-partisan Cook Political Report puts it, “by my math, in 2016, Donald Trump carried 76 percent of counties with a Cracker Barrel but 22 percent of counties with a Whole Foods Market”. Anyone who has been to America will know that Whole Foods only inhabit smart cities and Cracker Barrel is the staple of road-trips through the deep south. Mr Wasserman’s metric of division is dismally accurate.

Who cares? Everyone should, who loves America. Because to love America is to believe that the bow and arrow hunters matter. The Norman Rockwell small towns matter. Also: the old men on rocking chairs outside cafes as those improbably long freight trains rumble through once-wealthy junctions. The gun-nuts. The zealots — black and white — who go to separate churches in southern summer heat but pray to the same God. The passport-less folk who wonder if you, as a passing Englishman, know the Queen.

Without this tapestry, what is America? Hollywood? Silicon Valley? Wall St? Washington DC? Untethered from the centre, what madness will these institutions unleash? Harvey Weinstein and Bernie Madoff will look like pussycats. President Kardashian will not even pretend to know where Kansas City is. So yes, worry for America. Not for Trump’s America; but for what follows. Which could well be a lot worse.

Interestingly, Patrick Deneen’s recent review in First Things of The New Class War: Saving Democracy from the Managerial Elite by Michael Lind lends credence to Webb’s concerns. Deneen’s essay, titled “Replace the Elite,” details precisely why he and Lind do not believe that the elites are willing to share power with the rubes Webb described. He also explains why the backlash to the elites as represented by Donald Trump is likely not sustainable in the long-term:

Lind does not believe that populists have the answers…Instead of cheering their ascent, he argues for a rebalancing of wealth, political influence, and social power through what he calls “democratic pluralism.” Invoking older theories of “interest group pluralism,” Lind argues that the raw assertion of working-class political power is now needed to counteract the dominance of meritocratic neoliberalism. Echoing older theories of Aristotle and Machiavelli, Lind agrees that every nation is divided between the many poor and the few wealthy, and only a healthy balance of power between the two factions can bring domestic peace and stability.

Lind acknowledges that today’s elite are—for the moment, at least—unreceptive to this suggestion. They have adopted two defense mechanisms that justify their continued ascendancy and forestall consideration of their role in the destruction of the older political and economic settlement. The first of these reactions is the attribution of populist political success to external causes unrelated to class politics, particularly foreign manipulation. Believing that we live in a theoretically classless society—a “meritocracy” that allows the cream to rise to the top—today’s elite are incapable of accepting the most obvious reason for their electoral defeats, and instead embrace any number of conspiracy theories. Around every corner lurks either a Russian agent or a reincarnation of brown-shirt fascists. There are certainly some small number of both, but the frantic effort to condemn populism as a new totalitarianism is a willful act of denial.

The second reaction is the rise of “woke” leftism, which brings us the bizarre spectacle of wealthy elites rooting out racial and sexual injustice on ultraprogressive college campuses while ignoring the inequality that such institutions foster. The more elite the institution—and the more it monopolizes economic, political, and social advantage for its members—the louder its members denounce the racism, sexism, homophobia, and Islamophobia of the working class. Lind traces the origins of this tactic to the now-discredited theory of “the authoritarian personality” first advanced by a group of scientists led by Theodor Adorno. According to this theory, preferences for stability, traditional norms, the centrality of family, and geographic rootedness were evidence of psychological pathology. The opponents of the managerial class do not merely hold different values; they are psychotic and need treatment or institutionalization.

The managerial elite have an interest in prolonging these dismissive and condescending explanations indefinitely, but Lind asserts that what will make them face political reality—and, once again, concede some wealth, power, and status—is fear. Fear of losing their positions to populist replacements, Lind believes, is the only thing that can motivate today’s ruling class to limit low-skill immigration, narrow the economic divide, and express grudging respect for the traditional beliefs of the working class. His nightmare scenario is a protracted battle in which the elite refuse to cede some power, prosperity, and position, resulting in either an outright liberal illiberalism—an intensification of their present treatment of the working class and religious believers—or a demagogic populism that takes America down the road trod by many nations in Central and South America. His book implores his fellow elites to compromise now, or bear responsibility for losing the republic.

Lind is correct that fear is a powerful motivator, but I am skeptical that it will suffice in this case. The ruling classes of every age have had a great deal of success in squelching populist uprisings. In the American tradition, the subversion of populism has succeeded more through co-optation or patient outlasting than through violent suppression (though the history of violent suppression of organized labor should be recalled). America’s earliest populist uprising led to the Constitutional Convention and a new political settlement. Opponents correctly predicted that it would usher in a centralized government and an economic oligarchy that would leave ordinary citizens feeling politically impotent and voiceless. The Populist movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, though politically potent for the span of a decade, was eventually bled of its reformist energy by the technocratic, anti-traditional, and elitist Progressive movement. The working-class gains of the 1950s—made possible by the unique circumstance of total military mobilization and the existential threat posed first by fascism and then communism—were largely disassembled within thirty years. Lind’s belief that fear will motivate today’s woke capitalists to provide anything more than Band-Aids to the working class seems belied by the evidence.

By Lind’s own telling, the high-water mark of the 1950s was not the result merely of concessions from an otherwise neoliberal ruling class. Rather, the ethos of the ruling class itself was broadly in line with the values and ethos of the working and middle classes. It wasn’t merely the power of labor unions, local politicians, and religious congregations that forced the managerial elite to respect their demands. The elite actually shared in the organizations of “guild, ward, and congregation,” and thus had a different governing philosophy than the individualistic meritocratic calculus of today’s managerial elite. The sorts of communal organizations that drew on, and cultivated, broadly Catholic values of solidarity and subsidiarity were not restricted to dominantly Catholic working classes but informed the ethos of mass and elite alike. There was an alignment of values between corporations, small business, and Main Street. Hollywood produced and lionized such films as The Song of Bernadette, Boys Town, and It’s a Wonderful Life. Religious figures Fulton Sheen, Billy Graham, and Reinhold Niebuhr were admired across classes. The ruling class was not made up of secret neoliberals who grudgingly made concessions to the rubes in flyover country—they were “midwestern” in their broader ethos, steeped in the mid-century values of guild, ward, and congregation.

Not unlike the managerial elite he criticizes, Lind fails to draw the correct conclusion from his own analysis. What’s needed is not “democratic pluralism” in which the ruling class remains a neoliberal, managerial elite who strategically concede some wealth and status to their inferiors. What’s needed is a fundamental displacement of the elite ethos by a common-good, popular conservatism that directs both economic goals and social values toward broadly shared material and social capital, toward the support of family and community life. We do not need libertarian overlords who buy off the working class with some welfare, nor a federal government that doles out tax receipts to localities, nor secularists who grudgingly grant some space to religious believers, but a ruling class that is itself informed by the very values that Lind believes were once regnant as the price of admission to elite status itself. Only the fear of not conforming to the regnant ethos will sufficiently move elites, but that fear will arise subsequent to the wholesale defeat, displacement, and discrediting of the regnant elite ethos.

This means, contra Lind, that what is needed is not “democratic pluralism,” which Lind envisions as a balance of power between an otherwise exploitative ruling class and an electorally powerful underclass. Rather, the current ruling class needs to be displaced by the ethos of the underclass: people shaped by and supportive of guild, ward, and congregation. The ruling class, no less than the working class, should be shaped by commitments of solidarity and subsidiarity, and not merely accord grudgingly with those who are. Lind regards the revival of such institutions as the Church as an unrealistic goal and calls for some sort of functional equivalent. Yet the decline of organizational forms of unions, local politics, and Church has been significantly advanced by the individualist, materialist, and secular ethos embraced by today’s managerial elite. If these institutions declined due to sustained efforts by the managerial elite, their renewal can be effected through the displacement of that elite with a different one informed by an opposing ethos. The power sought is not merely to balance the current elite, but to replace them. In the end, there is no “functional equivalent” of solidarity and subsidiarity, and only a leadership and working class steeped in such values will restore the republic.

If you’re interested in what Deneen means by a “popular, common-good conservatism,” check out my recent interview with him, where we discuss the current divide in the American conservative movement, the potential rise of national conservatism, and what he thought of the National Conservative conference put on by the newly-formed Edmund Burke Foundation in Washington, D.C. last summer.

There have been many interesting analyses on what Trump’s rise means in the long-term—whether populism is a sustainable force, whether the Trump phenomenon is limited to a single powerful personality, and whether new electoral coalitions will form as the Democrats and the GOP duke it out for disaffected voters. What does seem clear is that elites are now openly discussing ways to ensure that this never, ever happens again—even if they have to expand the Supreme Court, abolish the Electoral College, and change the rules of the game until they are sure that they can never lose.

Pretty good essay here, with a few small quibbles. I would not agree that unions are a part of this ‘constructive conservativism’. I think that one of the foundational principles is entrepreneurship and the ability of anyone to live the American Dream by going in business for himself. What purpose does a union serve in these instances?

Unions by and large are a part of this institutional elite that prey off the weaker, helpless people. It bars many from using their talents to their full capacity, it restricts what a man may do for a living, who he can work for and where he can work. At one time, perhaps they had the concern of the worker at the forefront, but today they are a parasitic and bloated bureaucracy that launders cash stolen from the working poor to foster their hobby horses.