Blog Post

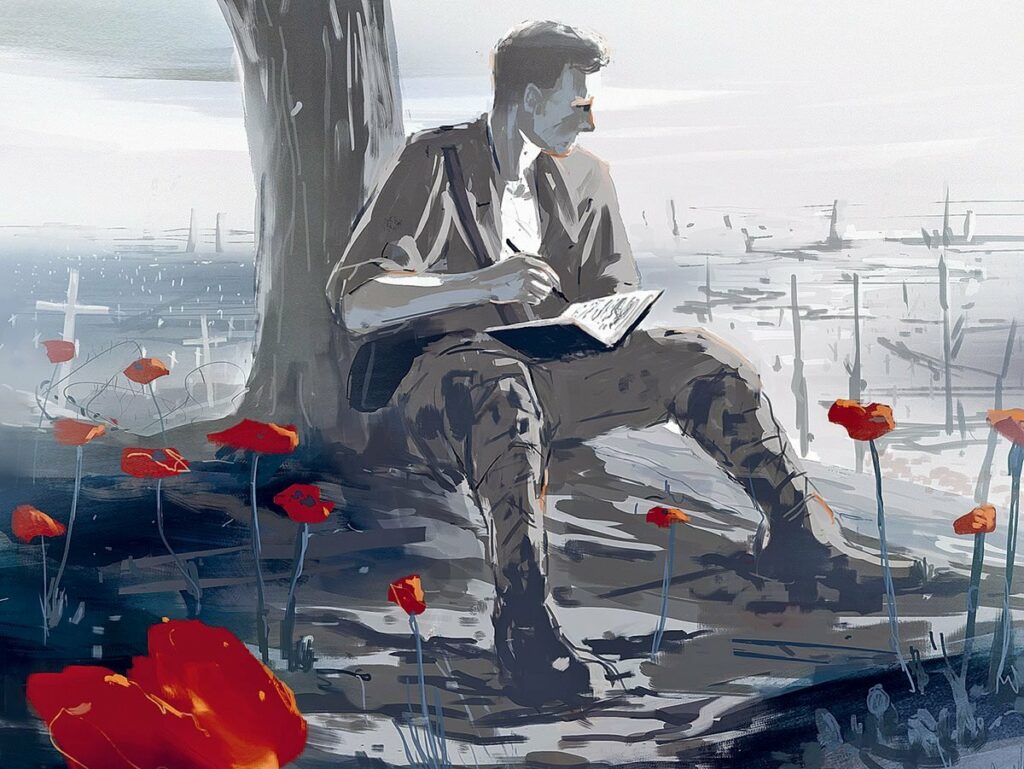

The Christian poetry of John McCrae

By Jonathon Van Maren

One of Canada’s least-known literary landmarks is a little limestone house in Guelph, Ontario. John McCrae, the great Canadian poet, was born there in 1872, and it now hosts a display where viewers can see a variety of Great War artifacts, some of McCrae’s belongings, and his Bible—given to him by the Ottawa Auxiliary Bible Society, along with a New Testament presented to him by the City of Guelph, back when the Scriptures were considered indispensable for men leaving for war. McCrae himself was a devout Christian, a fact that rarely surfaces in the sanitized biographies that preface the nation-wide recitations of his poem In Flander’s Fields, written in a dugout near Ypres just a few days before he, too, followed his fallen friends into eternity.

But what most do not know about McCrae is that In Flander’s Fields was not the only poem he wrote. He died young, and so did not have the opportunity to obtain the recognition that he undoubtedly deserves. But the few works that he did leave behind are as powerful as the lines that are chanted at cenotaphs across Canada on Remembrance Day, as the final notes of the Last Post fade into the grey November silence. One is titled “The Anxious Dead”:

O guns, fall silent till the dead men hear

Above their heads the legions pressing on:

(These fought their fight in time of bitter fear,

And died not knowing how the day had gone.)

O flashing muzzles, pause, and let them see

The coming dawn that streaks the sky afar;

Then let your mighty chorus witness be

To them, and Caesar, that we still make war.

Tell them, O guns, that we have heard their call,

That we have sworn, and will not turn aside,

That we will onward till we win or fall,

That we will keep the faith for which they died.

Bid them be patient, and some day, anon,

They shall feel earth enwrapt in silence deep;

Shall greet, in wonderment, the quiet dawn,

And in content may turn them to their sleep.

And then there are these searing stanzas from a poem he titled “Anarchy,” which seem to describe the secular savageries that ravaged the century after McCrae’s departure—lines that seem chillingly prophetic in so many ways:

I saw a city filled with lust and shame,

Where men, like wolves, slunk through the grim half-light;

And sudden, in the midst of it, there came

One who spoke boldly for the cause of Right.

And speaking, fell before that brutish race

Like some poor wren that shrieking eagles tear,

While brute Dishonour, with her bloodless face

Stood by and smote his lips that moved in prayer.

“Speak not of God! In centuries that word

Hath not been uttered! Our own king are we.”

And God stretched forth his finger as He heard

And o’er it cast a thousand leagues of sea.

McCrae is rightly remembered for the words that are carved into a grey memorial beside the house where he was born. When I visited, it was chilly, and dry leaves scratched their way across the ground near the concrete pavilion flanked by torches rises abruptly from the ground. But perhaps some enterprising English teachers will agree with me that he should be remembered for more than that, and that his story should be remembered for more than that of a soldier who wrote a single poem that helps us, each year, to remember the fallen Canadians across the ocean who claimed a little piece of foreign lands as their own by laying down their bones and breathing their last in defence of others.