Blog Post

The Forgotten Christmas Story by Charles Dickens

By Jonathon Van Maren

On a table in my library, I keep a copy of The Times from Saturday, July 10, 1858. Among other interesting news tidbits is this little advertisement:

MR. CHARLES DICKENS will READ, at St. Martin’s-hall, on Wednesday afternoon, July 14, at 3 o’clock, for the last time, his CHRISTMAS CAROL… Tickets to be had at Messrs. Chapman and Hall’s, publishers, 193, Piccadilly; and at St. Martin’s-hall, Long-acre.

The idea of scanning a fresh newspaper, lighting upon the advertisement—and purchasing a ticket to listen to one of the greatest writers of all time read from one of the most well-known novels of all time is a bit exhilarating.

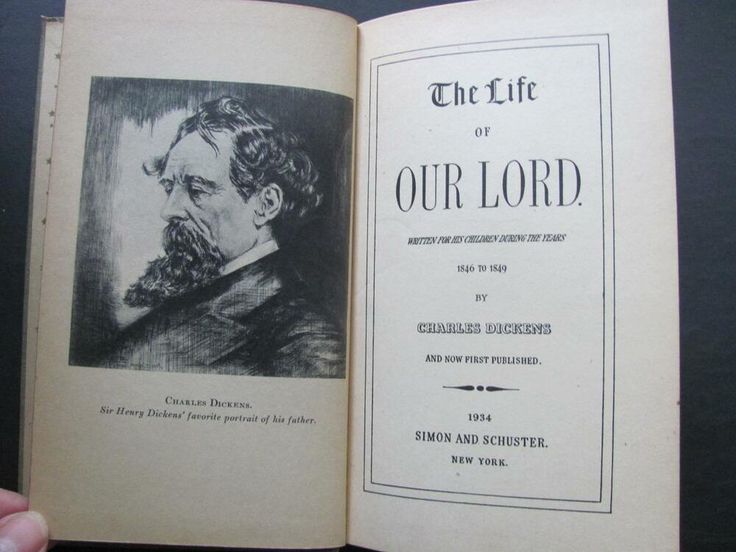

For more than a century, A Christmas Carol was easily one of the most famous Dickens stories in print. Recently, however, I came across another of his works that deals with Christmas—his almost entirely unknown book The Life of Our Lord, which was given the subtitle “Written for His Children During the Years 1846 to 1849” by Simon and Schuster in 1934. Dickens wrote the short volume—his summary of the Gospel of Luke—to be shared only with his family. Writing it during the time he was labouring over David Copperfield, Dickens called it a “children’s New Testament,” and he read it aloud to his family each Christmas. It begins:

My Dear Children,

I am very anxious that you should know something about the History of Jesus Christ. For everybody ought to know about Him. No one ever lived who was so good, so kind, so gentle, and so sorry for all people who did wrong, or were in any way ill or miserable, as He was. And as He is now in Heaven, where we hope to go, and all to meet each other after we are dead, and there be happy always together, you never can think what a good place Heaven is, without knowing who He was and what He did.

Dickens never intended the book to be published, and when his sister-in-law Georgina Hogarth asked him if he would allow it to be printed for private circulation, he declined. “He said I might make a copy of it for Peggy (Mrs. Dickens) or any one of his children, but for no one else,” she wrote, “and he also begged that we would never even hand the manuscript, or a copy of it, to anyone to take out of the house.” As great-great-grandson Gerald Charles Dickens noted: “The Dickens family felt that in return for such a wonderful gift, they must honor their father’s wishes. The clan closed ranks and protected their secret with great zeal.”

When Charles Dickens died in 1870, the manuscript was willed to Georgina Hogarth and, upon her passing, to Henry Fielding Dickens, the eighth of Dickens’ ten children. Henry, a lawyer, wanted The Life of Our Lord to have a wider readership, and while adhering to his father’s wishes, decided to give his children the option of making it publicly available. “Being his son I have felt constrained to act upon my father’s expressed desire that it should not be published, but I do not think it right that I should bind my children by any such view,” he wrote in his will. He stated that upon his death, his wife and children could decide whether to publish it by majority vote, with any proceeds being divided equally among them.

READ THE REST OF THIS COLUMN HERE