Blog Post

RIP Mark Crutcher, the investigator who founded the “CIA of the pro-life movement”

By Jonathon Van Maren

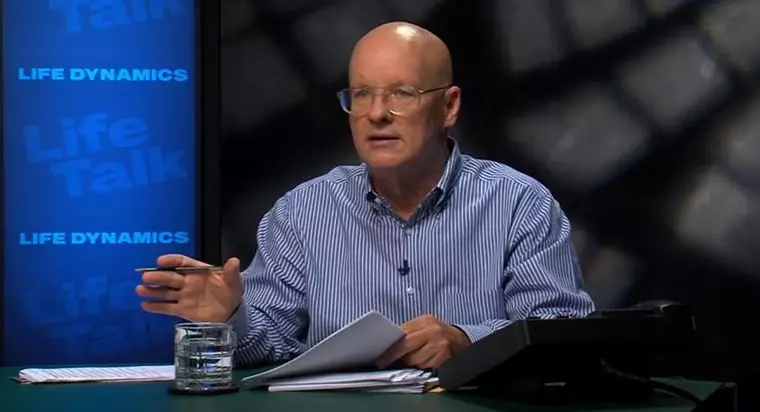

Pro-life icon Mark Crutcher passed away earlier this month from a heart attack at the age of 74. Crutcher was well known for pioneering the tactics of pro-life undercover investigative work, releasing reporting that pulled back the veil on the abortion industry and exposed their coverups of sexual predation and other abuses. His organization Life Dynamics, which he founded in 1992, earned the nickname “the CIA of the pro-life movement,” and his strategies inspired Lila Rose of Live Action and David Daleiden of the Center for Medical Progress to launch their own successful undercover investigations into the abortion industry.

When I asked him several years ago how he first got involved in the pro-life movement, he laughed. “You don’t choose the pro-life movement,” he told me. “It chooses you.” Crutcher cut his teeth in the mid-1980s doing debates with abortion advocates while also working for the auto industry until abortion activists put out the word that he was to be avoided and his challengers dried up. Instead, he began to run packed training seminars on how to debate abortion called Life Activists Seminars, training over 15,000 pro-life advocates across North America.

His first book was an 86-page self-published manual titled Firestorm: A Guerrilla Strategy for a Pro-life America. The movement, Crutcher wrote, needed to recognize that an ideological war was underway in which real corpses were piling up like cordwood. The abortion industry needed be exposed and stigmatized by activists who were willing to do what it took. What the babies needed, Crutcher told me, was “full-time mercenaries for the unborn.” A wealthy businessman somehow got his hands on it, read it, and reached out to Crutcher with an offer to fund his work. Life Dynamics launched soon thereafter.

When Crutcher stated that the abortion industry needed to be stigmatized, he was serious. One of his first major projects involved producing joke books about abortionists, which he had illustrated by a cartoonist. One was Bottomfeeder; another was Quack the Ripper, “news from the red-light district of medicine,” which depicted abortionists as “drooling psychotics.” They were mailed out to tens of thousands of medical students, and the media—and the abortion industry—went berserk. Ten years, later, they were still holding press conferences about it. The stigmatizing effect, Crutcher recalled, was hugely successful. “Now, all they can hire are the dregs and the losers and the degenerates.”

But Crutcher’s greatest contribution to the movement—and to the babies—was his pioneering undercover investigative work. “Everything we need to know about how to defeat the abortion industry is inside the abortion industry,” he told me. Abortion workers might not change their minds, but their businesses could still be shut down if abuse and malpractice were exposed. Crutcher’s investigations not only exposed the abortion industry, but the media, as well—instead of covering his findings, most instead sought to make his investigative methods the story rather than the crimes these methods had uncovered.

Mark Crutcher leaves behind his wife Tulane and their daughter Sheila. All who knew him will miss him dearly. Legions who never knew him live today because of his life’s work.