Abortion, Literature

The Pre-Persons: Philip K. Dick’s Forgotten Abortion Horror Story

Few science fiction writers have acquired the pop culture success of Philip K. Dick. The politically promiscuous writer authored 44 novels, over 120 short stories, and saw many of his works adapted for the big and small screen, including Blade Runner, The Man in the High Castle, and Minority Report. But few know that Dick also wrote a savage short story in response to the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision. That is no surprise—it is difficult to find, having been left out of all but two of his short story collections.

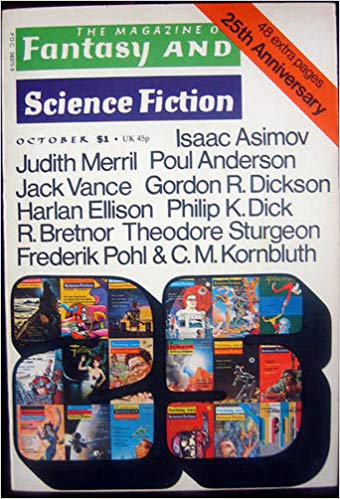

Dick completed “The Pre-Persons” in the months after the US Supreme Court imposed abortion on all fifty states, and Fantasy and Science Fiction magazine published it in October 1974 (I had to track down a copy on eBay to read it). The story, when published, caused a stir; feminist fantasy writer Joanna Russ wrote him with “absolute hate” that she would like to beat him up. He received death threats, too.

Dick was unmoved. “I admit that this story amounts to a special pleading,” he wrote, “and I’m sorry to offend those who disagree with me about abortion on demand…Well, I have always managed to offend people by what I write. Drugs, communism, and now an anti-abortion stand; I really know how to get myself in hot water. Sorry, people. But for the pre-persons’ sake I am not sorry. I stand where I stand: ‘Hier steh’ Ich; Ich kann nicht anders,’ as Martin Luther is supposed to have said.”

It is easy to see why the story, fresh on the heels of the Supreme Court ruling—now, of course, overturned–struck such a raw nerve. Abortion activists had persuaded themselves that Roe v. Wade settled the feticide question. Dick’s story unflinchingly followed their logic to its natural conclusion. If the right to life is contingent on age or some other arbitrary characteristic, what—or who—might be next? “The Pre-Persons,” which takes place in a future America when the abortion limit has been shifted to age twelve, opens with a chilling scene:

Past the grove of cypress trees Walter – he had been playing king of the mountain – saw the white truck, and he knew it for what it was. He thought, That’s the abortion truck. Come to take some kid in for a postpartum down at the abortion place. And he thought, Maybe my folks called it. For me.

The “abortion truck” was not coming for Walter, but his mother’s reassurances reminded me of the rage pro-life activists so often face when displaying abortion victim photos in public. When pro-choice people angrily demand that children be shielded from photos of the procedure that they support, it is in part because they have no good answer to the questions that pro-life signs might elicit from their children. I remember a child asking “Who broke the baby?” while her mother angrily yanked her down the sidewalk.

What was she supposed to say? “I support that, but not for you?” Or as Dick puts it:

‘Listen, Walter,’ Cynthia Best said, kneeling down and taking hold of his trembling hands, ‘I promise, your dad and I both promise, you’ll never be sent to the County Facility. Anyhow you’re too old. They only take children up to twelve.’

‘But Jeff Vogel–’

‘His parents got him in just before the new law went into effect. They couldn’t take him now, legally. They couldn’t take you now. Look – you have a soul; the law says a twelve-year-old boy has a soul. So he can’t go to the County Facility. See? You’re safe. Whenever you see the abortion truck, it’s for someone else, not you. Never for you. Is that clear? It’s come for another younger child who doesn’t have a soul yet, a pre-person.’

“The Pre-Persons” is a horror story because it is barely fantasy. Walter talks with other children about the boy the abortion truck had come for; how he had yelled as he was crammed into the back. Walter thinks about the law, and how it said that children who are “pre-persons” didn’t have a soul and were not yet human. The evil of it was obvious to him; the logic of it was not. The children in Dick’s story suppress their fears by fantasizing about what they would do to the doctors if they could.

Abortion trucks rove about the countryside, “pre-person” children hunched in the back, hunting for unwanted “strays.” As one driver puts it: “And what’s the difference between a five-month-old fetus and what we have here?” It isn’t a joke. The response: “In both cases what you have is an unwanted child. They simply liberalized the laws.” Indeed. Dick makes this point ruthlessly and explicitly:

The whole mistake of the pro-abortion people from the start, he said to himself, was the arbitrary line they drew. An embryo is not entitled to American Constitutional rights and can be killed, legally, by a doctor. But a fetus was a “person,” with rights, at least for a while; and then the proabortion crowd decided that even a seven-month fetus was not “human” and could be killed, legally, by a licensed doctor. And, one day, a newborn baby – it is a vegetable; it can’t focus its eyes, it understands nothing, nor talks. . . the pro-abortion lobby argued in court, and won, with their contention that a newborn baby was only a fetus expelled by accident or organic processes from the womb. But, even then, where was the line to be drawn finally? When the baby smiled its first smile? When it spoke its first word or reached for its initial time for a toy it enjoyed? The legal line was relentlessly pushed back and back. And now the most savage and arbitrary definition of all: when it could perform “higher math.” That made the ancient Greeks, of Plato’s time, nonhumans, since arithmetic was unknown to them, only geometry; and algebra was an Arab invention, much later in history. Arbitrary.

Dick makes his point with a club at times, although the story showcases his signature skill. He sneers at the myth of overpopulation and notes that the unborn are “the most helpless creatures alive.” Walter’s father wonders, after his wife suggests an abortion: Where did the motherly virtues go to? When mothers especially protected what was small and weak and defenseless? It is these questions, I suspect, that triggered the wrath of Joanna Russ and other pro-abortion writers who felt Dick’s scalpel words hit home, just as he intended.

Most of our culture’s elite storytellers are pro-abortion; that is why “The Pre-Persons” has never been adapted for the screen and has not been republished in nearly four decades. Stories shape culture, and abortion activists own virtually all the major franchises. The past few years have seen the propaganda machine ramp up with a stream of abortion films: The Janes; Unpregnant; Never Rarely, Sometimes Always; Obvious Child. In every story, the pre-born baby—the “un-person”—is utterly absent. The central figure, the main character, in the moral debate that has roiled America for a half-century is erased from stories fundamentally about their presence in the lives of others.

“In ‘The Pre-Persons’ it is love for the children that I feel, not anger toward those who would destroy them,” Dick explained. “My anger is generated out of love; it is love baffled. I hope you can see this in even this story. If not, then I’ve failed…” Love baffled, incidentally, is as good a phrase as any found in the story. In the post-Roe abortion wars, we desperately need writers of Dick’s calibre to turn their attention once again to those millions of “pre-persons” crowding like ghosts at the edges of America’s collective consciousness, demanding to be heard and seen. This is their story, too.