Blog Post

Real people are being hurt by the left’s New Witch Hunt, and they don’t care

This review was first published December 21, 2016.

By Jonathon Van Maren

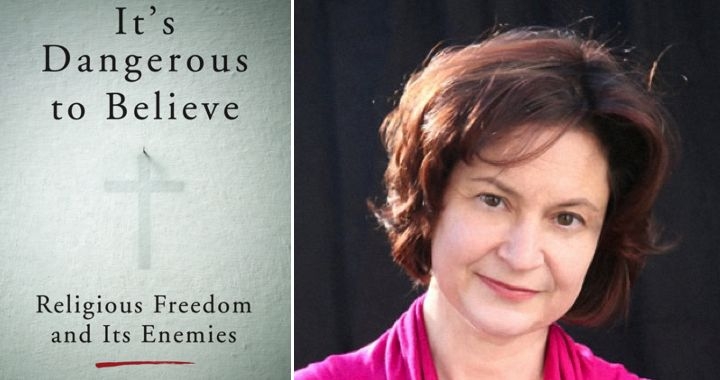

The eventful year of 2016 is over, and as the holiday season approaches and busy schedules perhaps allow a bit more time for some reading, I have an urgent recommendation for you: Get your hands on Mary Eberstadt’s short but powerful book It’s Dangerous to Believe: Religious Freedom and Its Enemies. It’s only 126 pages long—I read it in a few hours—but it lays out succinctly and with beautiful clarity what she calls the battle of the creeds, the war between the Sexual Revolution and traditionalist Christianity that has been waged with increasing sound and fury since the advent of the Pill.

When Eberstadt refers to the targeting of “Christians,” she is of course referring to traditionalist Christians—those who still hold to the two-thousand-year-old teachings on sexuality that Christians have always believed. This is a distinction that is now necessary. The Sexual Revolution has managed to generate a contingent of religious quislings, “progressive” Christians who have more or less abolished notions of sexual sin but magnanimously want to keep a messiah around to forgive their neighbors of the sins of homophobia and judgementalism. But these Christians are a very new breed. This new “progressive” Christianity is not only less than a century old, but already shrinking—a recent report noted that it is conservative churches that are growing while liberal churches continue to empty out, putting a bit of irony in the claims of so-called progressive Christians that they are “on the right side of history.”

It is worth noting, for a moment, that if Christians with the traditionalist view of sexuality were placed on one side of a scale, and progressive Christians were plopped on the other side, the sheer lopsidedness of the scene would be rather hilarious. On one side, we have everyone from St. Paul to the great Christian martyrs, from Tolkien, Chesterton, and Lewis, to Jonathan Edwards, Augustine of Hippo, and even the liberal Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. On the other side, we have a handful of so-called progressive Christian intellectuals—and who can name any? —who have abandoned two thousand years of Christian teaching, announcing with staggering arrogance that everyone else was wrong. When the weight of history is dropped onto the scales, it lands on the traditionalist side with such force that such progressives are flung into the stratosphere.

But secular progressives and their post-Christian cronies have made such advances because the position of religion in society has been weakened so much in the first place. So-called progressive Christians are really just hybrid heretics, as they do not see themselves as abandoning Christianity, but rather attempting to reconcile our culture’s two warring creeds. To announce loud support for gay unions, the transgender agenda, abortion, and the other secular sacraments while attempting to twist into a theological pretzel that allows one to claim that such beliefs are actually an expression of “Christian love” may seem to be a solution to the problem of “picking a side,” but in reality it makes a mockery of everything Christianity has ever stood for and a fool of the one attempting this oil-and-water cocktail. This is why we often see “progressive” Christians turning on their supposed co-religionists with such fervor—they are virtue-signalling to their secular comrades, and displaying the fierce eagerness that collaborators so often do.

In Eberstadt’s view, there were two main events in recent history that weakened the standing of religion in society: The Catholic priest child abuse scandals and subsequent cover-ups, which dramatically decreased people’s trust in “organized religion,” and 9/11, which made many people feel as if religion was a dangerous and toxic set of beliefs that could, after all, inspire men to fly planes into buildings. The growing creed of secular progressivism responded with its own apostles in the form of the New Atheism movement, led by the “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse”—Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and Daniel Dennett. What was new about this atheist movement, it turns out, is that it sounded rather familiar—the child abuse scandal gave the evangelists of New Atheism fodder for all the moral fury and righteous indignation they needed for an anti-religion crusade. The New Atheists, with no sense of irony, began a moral panic: Religion poisons everything. (One of my friends and I used to joke that Hitchens did in fact believe in objective morality, he was simply offended that it predated him.)

In other words, it is not that secular progressives don’t believe the Devil doesn’t exist. It’s just that they believe he happens to be a Christian. It’s not that they don’t believe in saints and sinners, it’s that in their creed, saints and sinners have swapped places.

This segued nicely into the ongoing demonization of Christians by the sexual revolutionaries. Christians were “homophobes,” “transphobes,” “bigots,” and “haters.” Consider for a moment, Eberstadt pleads with the reader, just how repulsive and ugly it is that millions of people are being convicted by smear campaigns of being hateful without evidence—their Christian beliefs alone are the only proof necessary to prove that they have hate in their heart. Hate, when detached from what any person actually feels, simply becomes a meaningless word. Eberstadt lays out, in careful detail, the absurd but stunning parallels between the ongoing stigmatization of Christians and the witch-hunts of 1600s Massachusetts. Secular progressivism, she reiterates, is a form of religion—and it sees the Christian view of sexuality as an original sin.

In other words, it is not that secular progressives don’t believe in the Devil. It’s just that they believe he happens to be a Christian. It’s not that they don’t believe in saints and sinners, it’s that in their creed, saints and sinners have swapped places: An athlete announcing his homosexuality can get a congratulatory call from the President of the United States, while a pastor renowned for his work combatting human trafficking can be forced to withdraw from offering a prayer at that same president’s inauguration as the result of a smear campaign targeting him for his Christian position on marriage.

Some may find the word “persecution” to be too strong a word to use in describing what is going on today in the West, and Eberstadt recognizes that. She does, however, detail very carefully the type of targeting that is going on: People losing their jobs, losing their businesses, being ostracized in social settings, refused admittance to universities, and finding their right to educate their own children under attack. Secular progressives are even targeting home-schooling while insinuating that Christian parents are a danger to their own children by virtue of the beliefs they teach. This fundamental right—the right of parents to pass their beliefs on to their children—is where most Christians, even those who simply wish to be left in peace, will finally draw the line and join the culture war.

Additionally, Eberstadt lays out the horrors of real, physical persecution that are being inflicted on Christians in Iraq—and asks, pointedly, why our secular progressive leaders do not seem to care. Indeed, there seems to be a backlash against the mere suggestion that Iraqi Christians, who like the Yazidis are often targeted for persecution by both ISIS and Muslims in the refugee camps, be prioritized because they are in the greatest danger. The reason vicious persecution the world round is ignored and escapes mention, while Barack Obama uses National Prayer Breakfasts to berate Christian leaders for historic sins, Eberstadt posits, is because those being persecuted are Christian, and secular progressives have no sympathy for Christians.

In the creed of the secular progressives, everything hinges on sex. Christians can believe, without controversy, that stealing, murder (except for abortion and euthanasia), lying, and swearing are wrong. If sex enters the picture, however, suddenly everything changes. It is for this reason that secular progressives are willing to hurt thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of poor and needy men, women, and children in order to inflict damage on Christian charities that do not agree with them that two men have the right to raise a child simply because they want to. Eberstadt records one heartbroken adoption worker noting that once the Catholic foster system and adoption services were “sued out of existence,” who would take care of the children? The progressive heresy hunters, of course, would have already carried their torches and pitchforks over to the next guilty charity and begun their shrieking anew. The message to Christian charities, lauded for decades even by secular sources for their sterling work with needy children and their mission to serve the poor, is simple: Change your beliefs on sex, or we’ll shut you down. Just as we see with abortion and so many of the other secular sacraments, children can always be sacrificed in the name of sex.

It is worth noting, as Eberstadt does, that this is not a theoretical question. Real people and real children are being hurt badly by this war against Christian charities, carried out by fanatics who would rather deny people life-saving services than agree to disagree on moral beliefs. If Christians are forced out of charity, much of the charitable system will implode, especially since religious people are far more likely to give to charity than secular people are. For example, people who pray every day are 30% more likely to give to a charity than people who do not pray, people who devote time to a spiritual life are 42% more likely to give to charity than those who do not, and interestingly, “people who say that ‘beliefs don’t matter as long as you’re a good person’ are dramatically less likely to give charitably (69% to 86%) and to volunteer (32% to 51%) than people who think that beliefs do matter.” Eberstadt’s chapter detailing the attack on Christian charities, titled “Inquisitors vs. good Works,” makes her book worth reading all by itself.

Eberstadt’s conclusion is a plea for common ground. Feminists and Christians, she points out, have found themselves fighting side by side on issues like pornography, surrogacy, and the objectification of women. It is possible for us to ascribe to the other the best possible motivation, while still disagreeing in the strongest possible terms. But for this to happen, says Eberstadt, the secular progressives must shut down their witch-hunt. They have to halt their demonization of Christians, cease their storming of Christian charities, and stop their attacks on Christian education. “Is the suppression of independent thought,” she asks, “really going to be progressivism’s historical signature?”

It certainly appears that way.

There are signs, however, that the public is beginning to tire of the witch-hunts. After all, the secular progressives are beginning to eat their own, like a snake choking on its own tail. Perfectly progressive professors like feminist icon Germaine Greer are finding themselves the target of protestors accusing them of being “transphobes,” and university administrators are finding themselves targeted or fired for infractions they were unaware existed until the accusations were launched. The tolerance buzz saw is whirring, and many are rapidly finding out that Christianity’s creed includes forgiveness, while progressivism’s does not.

So time will tell if a détente can be called and reasonable voices like Eberstadt’s will finally be heard above the din. But in the meantime, her call to sanity is a must-read for those who care about the future of our culture, and of civilization itself.