Culture, Travel Journalism

Peter Hitchens Reflects on 50 Years in Journalism

In the early morning of January 13, 1991, thousands of Lithuanians in the capital of Vilnius converged on the TV Tower. On March 11, 1990, Lithuania had become the first Soviet republic to declare independence from Moscow; Mikhail Gorbachev demanded that they renounce it. On March 17, the Lithuanians refused. KGB troops were sent in to quash the rebellion. As protestors surrounded the TV Tower, tanks drove into the crowds and the KGB opened fire. Fourteen people were killed; hundreds wounded. One of the journalists in Vilnius that night was Peter Hitchens. Witnessing history, he recalled, was one thing—getting the news to readers was another.

“The night after the Vilnius massacre, we were all trying to get copy out about what had happened,” he recounted. “The only telephones from which you could reach Moscow were in the Parliament building, which had been taken over by nationalist rebels who were convinced that the Russians would arrive that night. They’d filled the place with gasoline in tanks and hose pipes, intending to immolate themselves and anybody who came after them, and raided every construction site in the city with cranes and bulldozers and brought all the concrete blocks they could find and built a sort of medieval fortification around it. It was pretty frightening, but it was the only place with a telephone where I could call my wife in Moscow who would then transmit it to London.”

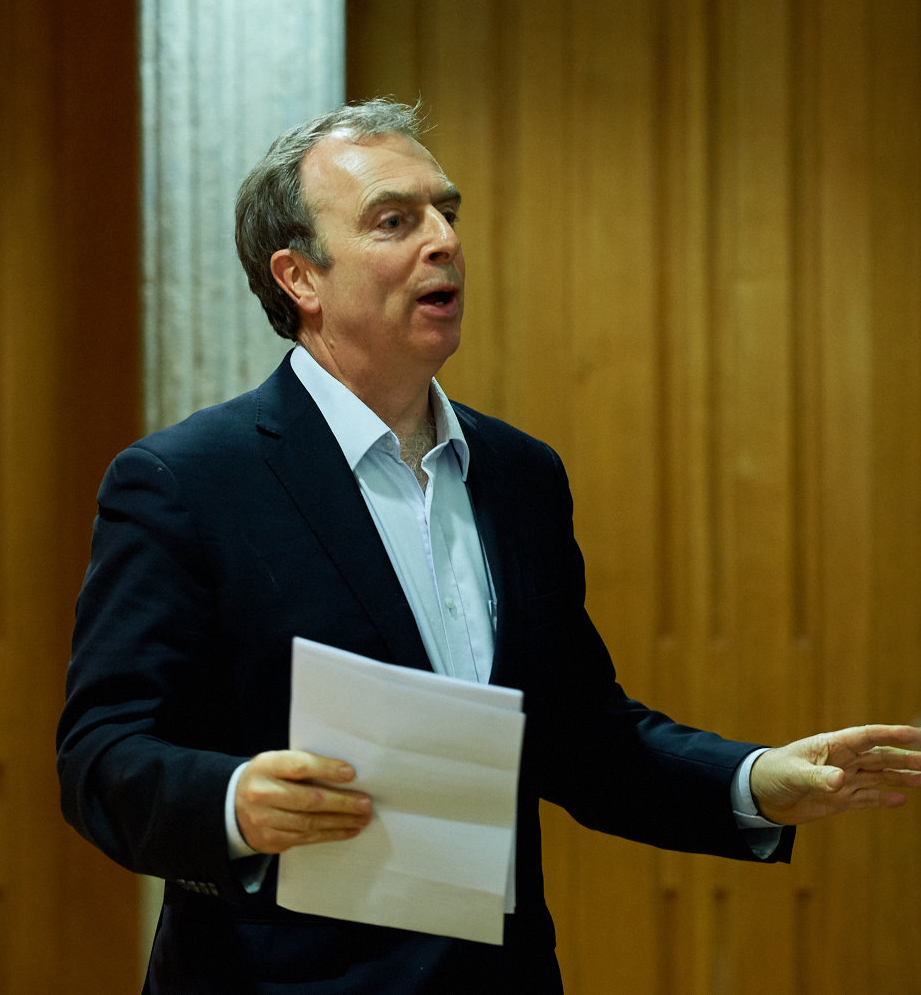

Peter Hitchens has many such stories; last year, he marked fifty years as a journalist. Currently a columnist with the Mail on Sunday, his career has taken him to 57 countries, including stints as a foreign correspondent in Moscow and Washington, D.C., and given him a ringside seat to some of the great historical events of the last century. He is now Britain’s best-known conservative polemicist with nine books to his name, including The Abolition of Britain, The Rage Against God, and The Phoney Victory. In 2010 he was awarded The Orwell Prize for his journalism, the UK’s most prestigious accolade for political writing. It was an honour he cherished; he “fell in love with George Orwell” in his middle teens after reading Orwell’s collected essays, and his desire to emulate that form of writing, he told me, has “always been the main thing that drove me.”

In an interview with The European Conservative, he reflected on his half-century in journalism. “I began to be interested in journalism early because I mistakenly thought it was about writing, which a lot of it isn’t,” he recalled. “I had a lot of fun producing family newspapers, school newspapers. Then I became a Marxist-Leninist revolutionary and I thought I could put what talents I had to the use of the revolution. That’s what propelled me into it in the first place, but as it happened, the experience of being a journalist was one of the things that made me cease being a Marxist-Leninist. I spent a lot of my teens in the city of Oxford, which is a kind of paradise separate from the real world. Then I went to a modern university campus in York, a sort of extraterritorial spaceship separate from the real world.”

Newspapers, however, were an introduction to the real world. “When I went into journalism, particularly at newspapers in provincial, industrial cities, I had to deal with normal human beings. It was revealed to me that I had a very poor understanding of what the world was really like,” Hitchens observed. “I had to revise that. I was pushed. The training you used to get in reporting—I was an indentured apprentice on my first newspaper—involved spending a lot of time with people like policemen, the fire brigade, and a lot of time in court, getting out and meeting the sort of people revolutionaries don’t have much time for, and discovering that they were not as advertised.” (The shorter version of Hitchens’s switch from callow Trotskyist to conservative: “I grew up.”)

His career began with shoe-leather reporting. “What I spent several years doing, from the late 1970s to the early 1980s, was covering what turned out to be a social revolution,” he said. “We didn’t know it at the time and didn’t recognize it as such, but those were the last great battles of the British labour unions. I was in a group of people, a quite distinguished and very intense group—almost a society within a society—who were engaged with this extraordinary thing. It was very melodramatic, kept us up late at night, got us up early in the morning, and forced us to go to unpleasant and uncomfortable places for a lot of the time. That was constantly exhilarating.”

While Hitchens didn’t much like reporting as such— “newspapers want concision and speed, not writing”—he did love the newspaper business. “There was a tremendous romance about it, but it’s all gone now,” he told me. “I’m very lucky to have seen the last of it. On my first newspaper we would often go down shortly before 12:45 to see the first edition going off the press. You could actually watch the amazing Victorian linotype machines with their pots of boiling lead and their dedicated operators and see it all made into those wonderful flongs and forms cast into the semi-cylinders, which were then cranked onto the machine and then the machine starting to run like a train going slowly out of the station to reach full speed—an amazing sight, the whole building trembling. The shouting, the tension, the speed—it was enormous fun.”

The job Hitchens really wanted was foreign correspondent, and on the advice of a veteran writer who told him that Prague was the last trace of 1930s Europe, he privately headed East. “I was completely entranced by the sinister glamour of it and the huge importance of what was going on,” he recalled. “I was captivated by Prague and by divided Berlin; to go on from divided Berlin into East Germany was enormously fascinating especially if you had been traveling in the West, because direct comparison between two systems of thought was possible. I did a lot of that, and when the moment came for my newspaper to revive its long-closed Moscow bureau after many years, I was a successful candidate for it. But I have to tell you, I tried very hard to get that job.”

Hitchens moved his family to the Soviet Union, where they lived from June 1990 to October 1992. It was an education, he said, that you couldn’t pay millions for. “It completely changed me and completely changed my life,” he reflected. “Moscow itself is one of the greatest cities that has ever existed. It’s enormous, quite a lot of it is staggeringly beautiful, and it is a tremendous stage for a great melodrama. It had me by the throat the whole time I was there. I’ve never gotten over it. I was glad to get out when I did because it was hard—everything you did took longer and was more difficult—but it was an extraordinarily valuable, unrepeatable experience. You can’t go there anymore. Soviet Moscow has vanished completely.”

The Hitchens family was fortunate in finding an exceptional place to live—an illegal let in a Communist Party elite building, where the Brezhnev family were just across the courtyard. “It was one of the loveliest places I’ve ever lived, but it was still Soviet,” Hitchens chuckled. “If I wanted to call home, I had to go through an immense procedure. Every so often, my phone would shut down because they were bugging it, and the tapes ran out. I had to go round to the next building where the exchange was, hammer on the door, and these beautiful girls would lean out the window and I would shout up”—here Hitchens briefly switched to Russian— “‘My phone, it doesn’t work!’ They’d laugh, and by the time I got back they’d have changed the tapes and the phone was working again.”

READ THE REST OF THIS COLUMN HERE