Travel Journalism

Edinburgh: Dead dogs and dead Christendom

Edinburgh, the “Athens of the North,” was windy, bracing, and fresh. We headed down the Royal Mile, Edinburgh Castle crouching over the city above us. Despite the buskers and the bustle, everything feels old here. The castle was once an Iron Age hill fort, and early medieval poetry claims that a “war band” feasted atop the rock for a year before “riding to their deaths in battle.” In 1314, the Scots took the castle from the English in a night raid led by the nephew of Robert the Bruce; in 1639, the Covenanters conquered it in less than thirty minutes during the First War of the Bishops by blowing up the front gate.

Charmaine and I headed first to St. Giles Kirk, founded in 1124 by King David I. It has been a working church for over 900 years; a black tile marks the spot where Queen Elizabeth II lay in state on September 12 and 13, 2022. St. Giles was the parish church of the great reformer John Knox, who preached from the ornate pulpit that now stands in its center and gleams from the stained glassed windows, the sun illuminating his fiery eyes and the scenes of his thunderous sermons.

The great Covenanter leader Archibald Campbell is buried along the wall; the ivory inscription reads: “Beheaded Near This Cathedral A.D 1661. Leader-in-Council and in Field for the Reformed Religion.” As a political leader, Campbell had once placed the crown on the head of King Charles II, before he himself was consumed in the wars of royalty and religion that followed. Above his sarcophagus, which features a statue of the great man lying atop it, are his final words: “I set the Crown on the King’s Head. He hastens me to a better Crown than his own.”

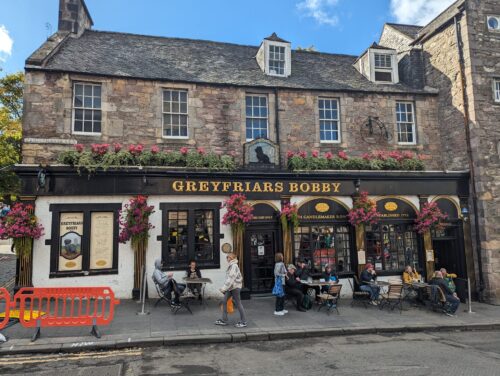

Based on his near omnipresence in statues, gift shops, posters, and more, the most famous resident of Edinburgh is a little dog named Greyfriars Bobby, a Sky Terrier belonging to John Gray, a night watchman for the Edinburgh Police. When Gray died of tuberculosis in February 1858, his dog spent the remaining fourteen years of his life sitting on his master’s grave, leaving it only for food and occasional shelter provided by the city residents who grew to love him. His story of loyalty became famous; the Lord Provost of Edinburgh paid for Bobby’s dog license himself, making him a ward of the City Council. Greyfriars Bobby had become a prominent fixture by the time he died in 1872.

I love a good dog story—I spent years of my childhood reading them—but by midafternoon the veneration of Greyfriars Bobby got a bit much. The Greyfriars Kirk is the first church to be built in Edinburgh after the Reformation, opening on Christmas Day 1620. It was also the scene of one of the great moments in Scottish history, when the Covenantors met to sign their “National Covenant” in 1638, pledging loyalty to the Crown but refusing King Charles I’s demands that they submit to Anglican liturgical practices.

Many of them paid for it with their lives; connected to the kirk grounds, visible through barred gates, is the infamous Covenanter’s Prison, where 1,200 Covenanters were held after the Battle of Bothwell Brig in appalling conditions, outdoors without shelter, starved, brutalized, and in some cases, executed. Many are buried in the kirkyard. The prison, however, is now closed to visitors (although the outdoor area can be viewed) due to staffing problems and, presumably, lack of interest.

The main draw now, apparently, is the dog. The grave of Greyfriars Bobby in front of the church is a giant, flower-filled garden, marked by a giant tombstone advising people to “Let His Loyalty & Devotion Be A Lesson To Us All.” People have placed flowers and teddy bears in front of it. Inside the Greyfriars Kirk, a pamphlet advertised a “Pet Blessing Service” where people are invited to “Bring your animals for an inspiring spiritual event featuring leaders of all faiths and none celebrating all of the animals.”

The “service” includes a “Pet Parade, Wreath Laying at Bobby’s Grave, and Human Reception following the service.” The pamphlet did not explain how a leader of no faith at all would contribute to the inspiring spirituality of the event, but the gift shop inside the church did include half a dozen books for children on the “Witch Wars” with the witches, of course, being the protagonists. Scotland is now a majority atheist country, and in a city where few care about souls, the intensity of religious fervor has been transferred to pets. This is likely exacerbated by the near-total collapse of Scotland’s birthrate.

Indeed, the city seems mildly embarrassed of her rich and tumultuous Christian heritage. When I asked questions about the Covenanter history, the apologetic attitude conveyed a very postmodern sentiment: Can you believe we ever fought about this superstitious stuff? (Meanwhile, the nose of the Greyfriars Bobby statue glows gold from the tens of thousands who have rubbed it for good luck.) In the Writer’s Corner of St. Giles Cathedral, the display lists everyone commemorated there (Robert Louis Stevenson, Margaret Oliphant), but does not mention the giant plaque of the theologian Thomas Chalmers on the wall nearby.

In fact, in the giftshop at St. Giles, I couldn’t find anything on the National Covenant at all, despite one of the original copies being on display inside the cathedral. There were no books about John Knox or the Reformation, either. There were, however, half a dozen different books about Greyfriars Bobby. The nearby St. Augustine’s United Church, meanwhile, featured a poster assuring disinterested passersby that they are a “Trans Affirming Congregation.” Across the street, we headed over to McCall Barbour’s Christian Book and Bible Shop to discover that it was permanently closed.

There was one place on the Royal Mile where the story of the Reformation can still be explored: The John Knox House. The gorgeous old mansion dates from 1470, and John Knox lived there for a few months before he died in 1572. The museum details, in fourteen “stations,” the history of the Scottish Reformation and the titanic clashes between Knox and Mary, Queen of Scots. In one ancient room lined with pews, sermons from Knox were playing and a giant portrait of the fiery-eyed preacher hung over the fireplace. The last station is Knox’s purported study, with a plaque on the wall containing one of his prayers:

And so I end. Rendering my troubled and sorrowful spirit in the hands of the Eternal God, earnestly trusting at His good pleasure to be freed from the cares of this miserable life and to rest with Christ Jesus, my only hope and life.

Despite the desecration of Edinburgh’s churches and the atheism of her inhabitants—the many Muslims we saw being the clear exception—Scotland’s Christian heritage still speaks from the cathedral walls and windows and cemeteries. You may not be able to hear sermons inside Greyfriars Kirk, but the graveyard around the cathedral still preaches. One Covenanter grave, topped by a Celtic cross, reads: “I must work the work of Him that sent me while it is day. The night is coming when no man can work.” Carved in the walls and on the gravestones throughout the kirkyard are eyeless skulls and bones, underlined by a solemn reminder: “Memento Mori.” Remember to die.