Blog Post

A day in the desert

By Jonathon Van Maren

Yuval was probably around sixty, but moved like someone much older. His facial expressions were either entirely impassive or wildly unimpressed. At the moment, he was also irritated. His white van had been idling at the curb of our Eilat hostel for a full thirty-seven seconds, and one of my three friends had yet to emerge. He looked at his watch and sighed so gustily that several papers on the checkout desk through the front door may have lifted just slightly.

Yuval was an Israeli tour guide we’d hired just the day before, at no small cost, to take us into Jordan for a day. Yuval had informed us by phone, in his gravelly, unimpressed voice, that we should be ready at precisely six ‘o’clock. This was apparently non-negotiable; as was the large pile of shekels he had demanded in exchange. When my friend came bounding out the door, all smiles, Yuval shot him a withering look and climbed laboriously back into the van. Yuval was not a morning person. He barked a string of Hebrew words at the driver, which seemed to me to be both directions as well as an unflattering assessment of the stupid Canadians that had followed him into the van. He then settled into silence in the passenger seat. If we were going to learn anything about Eilat on the drive, it turned out, we would not be learning it from him.

It was only around twenty minutes to the Jordanian border. Yuval began to give us instructions. As it turned out, he was not going to be actually taking us into Jordan himself. He was a former Israeli Seal, he said, and Israelis associated with the military—which I assumed was nearly all of them—were not allowed to travel inside Jordan. It’s easy to forget that Israel was at war with Jordan as recently as 1967. Yuval coughed horribly, and then glared at our concerned looks. He’d had cancer, he informed us. It developed from all the pollution in the water off the Haifa harbor. He’d spent a lot of time diving there, he added mysteriously.

My friend Will looked very suspicious at Yuval’s assertions of military prowess. This annoyed Yuval greatly. “You don’t believe me?” he demanded. He immediately launched into a number of stories from his military days, examining our faces throughout to ensure that we did, in fact, believe that he had been a magnificent warrior. I kept my face as impassive as possible. This seemed to be a great way to get some great stories.

A taxi pulled up and the girl we’d apparently been waiting for climbed out. Isabel was a young Jewish girl from Argentina, and Yuval’s irritation at tardiness apparently did not extend to her. He smiled warmly at her, and then loudly told us that once in Jordan, we had to stick together. As we walked towards the border crossing, he seemed to suddenly remember that his role as a tour guide perhaps demanded some level of courtesy.

“Look! You are still here, and already I miss you!” he called after us, and then looked slightly startled when I burst into laughter.

Getting into Jordan, it turned out, was easier than getting into the United States.

“Passports? Purpose of trip?” Ka-CHUNK. Passports stamped. And a string of cigarette-smoking Arab officials pointed us towards a chain-link fenced path that led to a parking lot and a giant white sign reading “Welcome to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.” Hashemite, of course, was the Jordanian royal family, who got to put their name on an entire country. Donald Trump would be envious.

In the parking lot another white van—a bit older, a bit dustier—was waiting for us, with a cheery middle-aged Arab inside. His name was Hassan, and it seemed as if he’d worked with Yuval in the past and was trying to make up for the crotchety veteran’s lack of enthusiasm. As the van lurched off down the bumpy road, Hassan talked nonstop, pointing things out.

It’s a good thing we had him, too, or I think all we would have seen was rocky desert, cliffs, and mountains colored a thousand shades of red stretching off into the distance. But as we bumped along through Aqaba and Amman towards Petra, Hassan found things to point at. There was Wadi Rum! he jabbed his finger excitedly. This was near Mt. Nebo, where God buried Moses. He nodded at us with satisfaction, satisfied that Moses was an important figure to us. There were sparse herds of goats picking their way through the rocks, looking for plants that I couldn’t imagine they would find. Regardless, they looked unperturbed and unhurried. The van swerved over to the side of the road for a moment, precariously close to the edge of a cliff. Hassan pointed at a tiny pile of rocks atop a mountain.

“That is where Haroun was buried.” Haroun? Ah, Aaron, Moses’ older brother, the high priest of Israel. It’s easy to forget that many of the figures revered within Judaism and Christianity are also revered by the Muslims. The desert air was crisp, and the moon sat high in the clear noon sky above the tomb of Haroun.

“That is where Haroun was buried.” Haroun? Ah, Aaron, Moses’ older brother, the high priest of Israel. It’s easy to forget that many of the figures revered within Judaism and Christianity are also revered by the Muslims. The desert air was crisp, and the moon sat high in the clear noon sky above the tomb of Haroun.

There were Bedouin camps here and there, too, and when I looked closely I could see Arab shepherds meandering after the goats. No one seemed in any particular rush. There were camels here and there, as well. Hassan informed us that camels are actually incredibly intelligent creatures, and if mistreated, can actually wait up to five years to get their revenge with sudden, well-placed vicious kicks or chomps. Suddenly, all the camels I saw looked suspicious and sleepily malevolent, as if each of them were nursing a herd of private grudges. They reminded me of Yuval, actually.

As the van kicked up a plume of dust through the mountains and canyons, Hasson began complaining loudly about the price of gas. Apparently, it used to be only fifteen cents a litre, because Saddam Hussein gave Jordan the oil for free. Then, of course, the Americans invaded Iraq, the Iraqis hung Saddam, and the oil stopped coming. Jordan plunged into an enormous recession that, according to Hassan, was just now beginning to relent. Fortunately, the peace deal with Israel that got Yitzhak Rabin shot has created a lot of tourism opportunities, which Jordanians such as Hassan take full advantage of.

At several points along the way, the van lurched into the parking lots of souvenir shops that were clearly owned by Hassan’s friends. In front of them, packs of wild dogs of all colors gnawed through piles of garbage. His friends tried to sell us souvenirs while I bought coffee. Coffee in the Middle East is frustrating, because they take the strength of an entire pot of Canadian coffee, boil it down into a miniature mug the size of a shot glass, ensure that it has the consistency of black tar, and then serve it to you. They then beam at you as you down your coffee and fight to stave off a coughing fit while the coffee burns a hole in your esophagus. On the upside, it does the trick. I was very much awake, which afforded me the opportunity to consider whether or not I would need to explore the intricacies of the Jordanian healthcare system.

We arrived at Petra in the early afternoon. Originating around 312 BC, Petra is an entire city of tombs, cisterns, homes, palaces, elaborate temples, and an irrigation system carved right into the rock. It’s the type of place that causes irritatingly unspecific words like “magnificent” spring to your lips simply because it seems as if such words were invented for just such places. John William Burgon tried to capture the essence of Petra in 1845:

It seems no work of Man’s creative hand,

It seems no work of Man’s creative hand,

by labour wrought as wavering fancy planned;

But from the rock as if by magic grown,

eternal, silent, beautiful, alone!

Not virgin-white like that old Doric shrine,

where erst Athena held her rites divine;

Not saintly-grey, like many a minster fane,

that crowns the hill and consecrates the plain;

But rose-red as if the blush of dawn,

that first beheld them were not yet withdrawn;

The hues of youth upon a brow of woe,

which Man deemed old two thousand years ago,

match me such marvel save in Eastern clime,

a rose-red city half as old as time.

The Nabateans began to carve the city here first, and the intricacy of the carvings—columns, sculptures, designs—was breathtaking. None of the crudeness of modernity has eroded Petra, except the chips and scars scattered across the temple facades here and there, the result of Bedouin warriors firing rifles to see if the stone faces concealed treasures. I wondered if the Nabateans would sneer at Canada’s mountain feats—holes blown into the Rockies that allowed our smoke-belching trains to cross the continent. Different priorities, I suppose.

When we climbed up into the mountains a way to get a better view, we could still dig shards of pottery and ancient irrigation pipe out of the sand. I stashed some in my backpack. Here and there, wizened Bedouin women hawked old coins and daggers and statues. I bartered with one ancient woman for an old janbiya dagger in a leather sheath. A coin embedded in the wooden handle told me it was made in 1918. That would be a year after Lawrence of Arabia led an Arab revolt against the Ottomans—the Bedouin women from around Petra joined in the fray, led by the wife of Sheik Khallil. This particular woman seemed old enough to actually remember such events. She certainly resented invaders, anyhow. She sold me the dagger anyway.

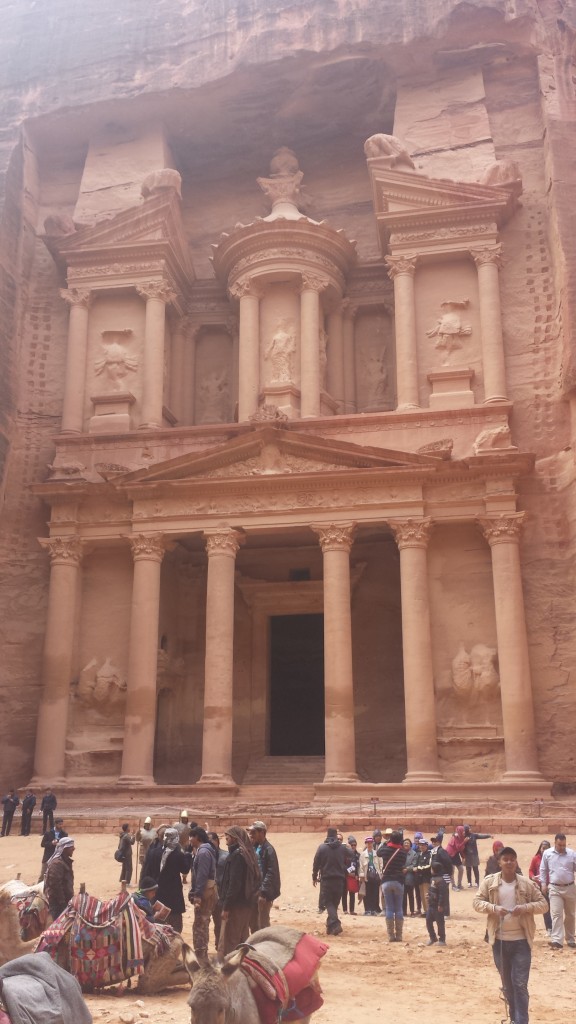

Petra had seen its fair share of invaders. The Nabateans, the Romans, and then the Muslims—the diverse influences could be seen everywhere, from the tombs to the cliff passageways that opened into canyons cradling what seemed like entire civilizations. For a time, one temple was turned into one of the oldest Christian churches in the world. The Treasury, Petra’s largest temple, towers 95 feet high. And in front, of course, were dozens of teenagers from around the world, taking selfies.

We climbed back into the van hours later, dusty, tired, and more than a little awed. As the van picked up speed and the plume of dust following us shot up higher into the desert air, I fell asleep in the backseat. I woke up with a start around an hour later—our van was burned out on the side of the road. We’d overheated in the desert, with nothing but rocky sand and sandy red rock as far as the eye could see. Hassan had already fished my Bedouin dagger out of my backpack to try and saw through one of the rubber belts under the hood, to no avail. Instead, we had to wait for another van to come and fetch us. Hassan’s mood improved upon the arrival of our new vehicle, and as the sun simmered and sank below the horizon and darkness stole across the sand, he attempted to sell us on the virtues of purchasing a sunny second home in Aqaba. We remained unconvinced, and Hassan’s renewed cheeriness remained unflappable. He dropped us off at the Israeli border with a handshake, a wave, and exhortations to return and see more of the Kingdom of Jordan.

The Israeli border guards, unfortunately, were not in nearly as good spirits. They soon discovered that I’d traveled to Jordan once before, and became quite certain that my journeys had more sinister intentions. I have no idea what sort of information they had on the computer they were eyeing, but the fact that I’d visited the Palestinian Territories and Egypt in 2008 did not alleviate their suspicions. I was pulled aside, seated, and subjected to a rapid-fire string of questions, which I soon noticed were almost identical, but simply worded differently. No, I have no friends in Jordan. No, I have no family in Jordan. I’ve been to Jordan twice because they have amazing historical sites to visit. That’s why I visited Egypt too, yes. No, I do not have any friends in Egypt.

Finally, they realized that it was extremely unlikely that I was capable of any terrorist plot, and that I was in all likelihood far too irritating to make any friends in Jordan, and waved me on through. Yuval was waiting for us on the other side of the border crossing, a clearly contrived grin-grimace that I suspected he’d been practicing all day plastered awkwardly across his craggy face. “You had fun?” he asked, emitting the word as if it tasted strange. “You bet!” we assured him. And to his great relief, we lapsed into sleepy silence as he drove us back through the brightly lit city of Eilat.