Blog Post

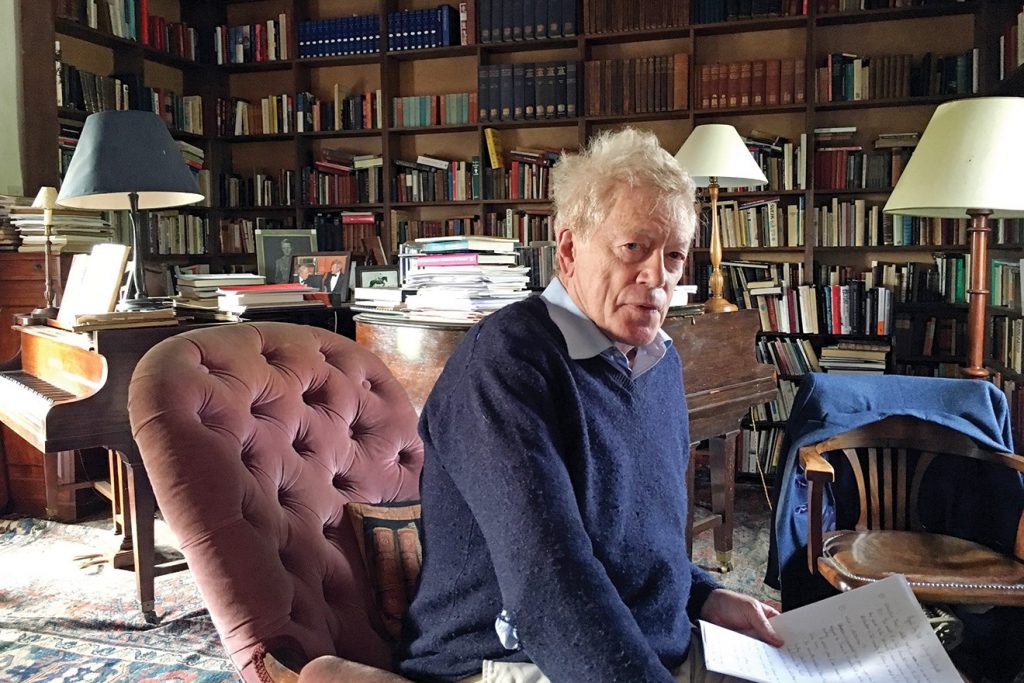

Defending Western civilization: A conversation with Sir Roger Scruton

By Jonathon Van Maren

Knighted in 2016 for “services to philosophy, teaching, and public education,” there is perhaps no academic so articulate and so fierce in his defence of Western civilization as Sir Roger Scruton. A graduate of Cambridge, anti-Communist Cold Warrior, professor in the Humanities Research Institute at Buckingham University, and author of over forty books, Scruton has spent decades pushing back against the progressive destruction of our collective Western heritage and advocating for its protection and renewal. In addition to his academic books such as The Aesthetics of Architecture and a BBC documentary titled Why Beauty Matters, Scruton is also the author of many essays, “invocations of country life,” novels, poems, and even an opera.

He has also consistently sounded the alarm on the cultural decline of the West, urging people to reconnect with their heritage and rebuking those who neglected their obligation to pass it on to their children and their grandchildren. Too many people, he has noted, have decided to reject the “burden” of their heritage, deciding due to cowardice or laziness that Western civilization has not produced anything worth defending or passing on. He has also advocated returning to church, pointing to the Judeo-Christian foundations upon which most of our nations rest as essential components of our civilizational survival.

Sir Roger Scruton was kind enough to join me for a conversation on these issues some time ago.

How would you describe your work?

Essentially, I’ve always identified myself as a writer and a philosopher. My work has always been dedicated to articulating a particular vision of modern society and Western civilization, which I’ve seen as being under threat in so many ways, but also containing so much of value that it is the duty of someone like me to express that.

You have said that you became a conservative after witnessing the protests and the riots in 1968 in France. How did that come about?

Well I was there in Paris, I’d been teaching in university for a year prior to that so I had a whole network of friends and that’s where I happened to be.

Many European journalists have been discussing the concept of cultural confidence, and this is something you’ve commented on a lot as well—about “forgetting” our cultural heritage and the roots of civilization. Can you explain what your conceptualization of cultural confidence is and why you think we’ve lost it?

I’m not so sure we have lost it—not entirely. I mean, there are people like me and Douglas [Murray] who are as confident as we’ve ever been. But it is true that the mass of educated people have lost something. The education system no longer emphasizes what distinguishes Western civilization from the rest of the world and certainly doesn’t emphasize the things that we can value in it. There is also a growing culture of repudiation among teachers, media, and the self-defining intellectuals who want to cast off the burden of their inheritance without having anything else they want to pick up and replace it with. This is something that is very difficult to explain, in a way, but it has something to do with the loss of our inherited religion and something to do with the fact that to stand up for anything always requires more courage than most people have.

The way you worded that is interesting—the “burden of their heritage.” G.K. Chesterton always pointed out that people do not simply repudiate their ancestors because of the wrongs they did, but because their achievements makes us feel very small, and we hate that.

Yes, that’s right.

What would your perception of that be? Both you and Douglas Murray point back to the Judeo-Christian tradition as something that preserved a part of the culture that now seems to be overlooked or lost entirely.

Everything that is valuable is in the end threatened because it is going to be as mortal as we are, and when people cease to defend their inheritance, or find it for the reasons that Chesterton says a burden, then it is without defenders and it begins to corrode and wash away. I was brought up to believe, as most of my generation were, that if you’ve inherited something good, it isn’t yours to destroy, it is your duty to pass it on—and that’s the hard bit. That’s a duty people would obviously rather escape than take seriously, like so many of their duties. What we are seeing in our education system—my teachers both at school and university felt an obligation to hand on what they’d inherited because it was something inherently good in itself. But it meant a lot of work, it meant combatting the stupidity of young people in order to get into their heads that there is something more important than themselves and that takes a lot of courage and determination. At a certain point, as a generation of teachers emerged, they found that they just didn’t have the impetus to do that. It was just not their thing.

One of the subjects you’ve often focused on is the subject of beauty, and that because our culture no longer knows how to define that and has no true philosophical conceptualization of what beauty is that we’ve forgotten how to make beautiful things. Inside the traditionalist movement in North America is a rebellion against modern architecture; modern buildings are garbage, and old buildings are beautiful. How would you make that relatable to a young audience? When you say we’ve forgotten beauty, how would you convey that idea?

It’s a very difficult idea to convey because there is so much propaganda being made—especially by modernists in architecture—for the idea that everything can be done anew. You can get rid of the old traditional ways of building, of harmonizing, of decorating and so on, and just produce these sterile geometrical shapes, and this is somehow the voice of the future. There’s a lot of money to be made by these sorts of people. Let’s face it, in Canada it’s been a disaster because you had a very fragile inheritance of architecture, a few little places that have beautiful downtown areas, but most of it was just swept away, and the new thing that replaced it is nothing more than drawing-board engineering, which produces temporary buildings of glass and steel which will be swept away in their turn. So you no longer have the idea of a beautiful settlement. A town becomes simply a temporary shelter, put up by multi-national businesses, and in those conditions, people can’t find in their environment anything beautiful at all unless they get out of the city altogether into the wild woods and lakes of the further country. I think that it’s been a great trouble for Canadians, and that’s one reason they find it so difficult to identify with their cities.

That’s not the only problem, of course. Beauty is not just a matter of architecture. It’s something that inhabits our entire life. It’s what shapes our taste in music, interior decoration, in painting, and of course above all in poetry and the written word. And that’s where I think the major defence of beauty needs to occur. We need to show people that in the things that are closest to them, in the things that really matter to them—for instance, their use of words, their gestures, their way of looking at each other, their way of dressing, of being close to each other—in all these things, there is a distinction between doing it right and getting the approval and endorsement of others which means doing something beautiful, and doing it wrong, which means alienating everything around you.

When I was speaking with Douglas Murray some time ago, he noted that when bad people are the only ones willing to advocate for good ideas we are going to be in for trouble. He was talking about tribalism, and it struck me that in your 2006 book Arguments for Conservatism you actually lay out and make the argument that humans have territorial loyalty, and that they’re going to be more loyal to the local than to the national or the international, and you said this before the identitarian movements began to sweep Europe like they have in the last five to ten years. When you see things unfolding, when you’d already laid things out for people to read if they’d wanted to, what is your response to all of this and how do you suggest we have less heat and more light?

A very good question. I’ve always assumed that it’s not for me to change the world, all I can do is record the truth as I understand it, and subject it to criticism and argument and see if we can come to consensus. But for there to be genuine change and genuine resistance there has to be more than one person, and it’s very difficult to ensure that—to ensure that people will understand what you’re trying to say. But it is a general truth, I think, that people only wake up to a situation when it’s too late to remedy it. This is something that Hegel once said: The owl of Minerva only flies in the dusk. I think we’re in that condition. People are waking up to some very important truths about the nature of human communities and what is necessary in order to survive and propagate, but they’re waking up to it at the eleventh hour.

“Eleventh hour” is by definition almost too late. I spoke with Peter Hitchens several times on this subject, and I noticed that while Murray kept on saying that we need to find a way forward, we need to fight for what we have left, Hitchens was more or less of the opinion that we could be getting on with writing Great Britain’s eulogy and that young people should move. There’s obviously a dispositional difference there that plays into those two different analyses, but who do you think is right?

Well. It’s an interesting question. I want to be on Douglas’s side on this, and I believe that in general one has an obligation to be optimistic, to find a solution even if it’s a compromise with things one doesn’t approve of—to relay a message of despair doesn’t help anyone, really. To say that it’s all over, and that young people should move, is great if you think that there’s somewhere for them to move to. But everywhere it is in the same condition. Okay, when it comes to the migration problem you can move to Russia—they’ll never have an immigration crisis, for obvious reasons. But who wants to move to Russia?

So I’m getting that your view is a dimmer one.

My view is that you’ve got to fight for what you have, and you’ve got to set an example. And you do it locally, and among people you know, but if you give up fighting than of course you will go down with the rest of mankind. Nevertheless, all is not lost.

You’ve spent a lot of time with young people, giving your lectures, and in traditionalist circles especially your work is extremely popular. There’s been two versions of rebellion among young European people: There’s the people who take the identitarian route, and then there’s the people saying to their parents, “You had no right to give this up on our behalf. You had an obligation to pass this on to us.” And they seek out work like your own, they start to read people like Murray and Hitchens (who told me that he has many young people seeking him out after reading books like The Abolition of Britain to talk about how it really resonated with them). So when you talk to young people who are increasingly aware that something was given up on their behalf that is a part of them, that says something about them that they have to know because their story is incomplete unless they do know it, how have those conversations given you a sense of either pessimism or optimism?

I get a lot of very positive feedback from young people of that kind, saying that I’m defining something for them that they had been looking for. They are always very grateful, because no one can live without an ideal of some kind, and the closer that ideal is to something near at hand and actual, the better. Because then they can say look, here is something I can work to make part of my life and not just be something on the distant horizon. So young people do respond very much as soon as you articulate what it is you love about your country and its traditions. They will be prepared to buy in, and this is very encouraging.

Chesterton once said that tradition is so strong that young men will dream of things they have never seen, and I always thought that defined it very beautifully. When young people approach you and ask you how they can start re-engaging with their traditions, what’s the advice that you give them?

There are plenty of things to re-engage with all around us. My own thought is that you should look for community activities which are yours, which are natural to you, which are part of your society, the discussions and debates you might have in college, the books that you might read together, and then there are of course the churches which stand waiting to be filled. There’s so much that people can engage with which is still there. Of course it would mean overcoming the embarrassment that might accompany making the first gesture.

When people look at cultural decay and the decline of cultural confidence, there are fingers pointed all over the place, and there are people giving good answers and people giving bad answers, and there are people giving complex answers like Dr. Jordan Peterson. What would your answer to that question be? Since the 1960s, what would you say contributed the most to the cultural decay we all face?

Well at the time, I suppose I blamed in particular the French intellectuals of the 1960s. I blamed people like Michel Foucault and all his entourage, Lacan and the people who attended his seminars, these I thought were highly destructive, almost demonic people whose one obsession was to rid the world of bourgeoisies and to bring up young people to hate what was all around them. I think that became a kind of disease which spread through universities, especially in America. Most French people after awhile got bored with them and recognized that they were posturing narcissists, but American professors for some reason went on taking them seriously right into our day. I think they have been to blame for a great deal of the loss of a sense of any intellectual heart.

When young people want to re-engage, especially in regard to literature and poetry, where should people start? In my conversations with people, I’ve discovered that one of the difficulties is that if you weren’t raised on the classics, it is very difficult to start. So how would you advise people to dip their feet in the water and carry on from there?

It is a difficult question. If you’ve been raised in one of the churches—especially the Roman Catholic or Anglican Church—you would suddenly be familiar with the Bible and the Gospels but also with a tradition of thinking about those things, which takes in the classics along the way. I think this makes it very much easier to think about our current situation. You could be a leftist, like Charles Taylor to take one of your thinkers, but if you have that upbringing it allows you nevertheless to grasp the complexity of the issues and why it is that there is a lot of tradition to be rescued.

One final question. Your own books cover many different topics from conservatism to sexuality. If people want to engage with your work, young people, where would you suggest they start?

That’s a very interesting question. I do write fiction as well as difficult philosophy and so on. I will say one always wants to sell one’s most recent books of course. I did write a book called The Soul of the World, which was my attempt to put my philosophy in a way that is both serious and opens the door to a religious way of looking at things that could be very helpful for young people. And there’s a novel called The Disappeared which is really an attempt to convey the situation our country and countries like us in the face of mass migration and the difficulty of holding on to things in that situation, but it’s a novel with a kind of optimistic and redemptive conclusion, which I know that young people who read have found quite gripping, so there’s something that they could start with.

_______________________________________________

For anyone interested, my book on The Culture War, which analyzes the journey our culture has taken from the way it was to the way it is and examines the Sexual Revolution, hook-up culture, the rise of the porn plague, abortion, commodity culture, euthanasia, and the gay rights movement, is available for sale here.