Blog Post

When the Rwandan Genocide began, one American refused to leave–and saved hundreds of lives

By Jonathon Van Maren

On April 6, 1994, the Rwandan Civil War was in its fifth year, but all was quiet. The Hutu-led government and the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) had been in conflict for years, but international pressure had finally resulted in a ceasefire in 1993, with Juvenal Habyarimana, the second president of Rwanda (he had been serving in that office since 1973) working to create a coalition government with the RPF at the table. But as Habyarimana’s plane, carrying both the Rwandan leader and the Burundian president, began to descend into Kigali, it was shot down. The peace talks were over, and Rwanda exploded into violence.

The genocide began the next day. Roadblocks sprang up everywhere, and soldiers, police, and militia launched killing sprees and a string of assassinations that eliminated top Tutsi leaders, along with moderate Hutus who might be willing to protest. Men, women, and children were hacked to death, mutilated, and raped in multiplying, unfathomable horrors. Hutu civilians became butchers overnight, attacking their neighbors with machetes and clubs. Foreign citizens fled the country, UN troops did nothing, and the world watched as Hutu killers massacred between 500,000 and 1,000,000 million people in only one hundred days—an estimated 70% of the entire Tutsi population. It would become an irrevocable stain on the reputation of the liberal international order.

The scars of this bloodshed are still everywhere in Rwanda today. When I visited several mass graves outside Kigali—crypts stacked to the ceiling with empty skulls and piles of fleshless bones—there were battered wooden pallets sitting outside some of the church buildings that serve as a memorial to the genocide, covered in blue tarps. When I asked what was on them, the young woman showing us around pulled the tarp back to reveal little heaps of bone shards—a fragment of jaw with a few teeth still clinging to it, a piece of a pelvis, a splinter of someone’s leg that had been chopped off. People were still finding these everywhere, she explained, and so some of the genocide sites serve as sort of a collection depot for human remains found in the jungle or in the pastures where people fell and died.

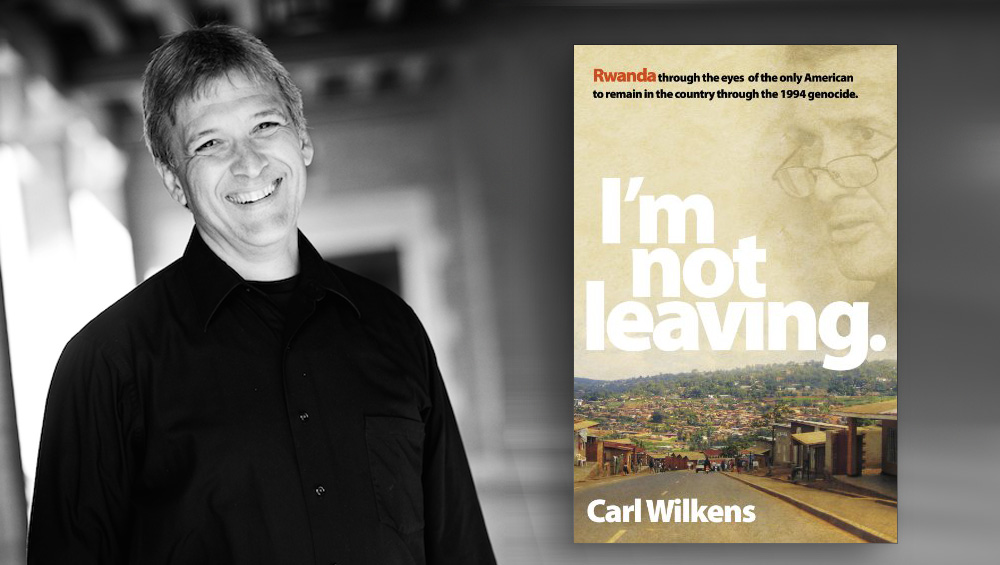

When the killing began, foreigners fled the country. In fact, only one American refused to leave: Carl Wilkens, a young husband and father who was serving with the Adventist Development and Relief Agency International. He grappled with his decision, but finally decided that he could not abandon his Tutsi friends to their fate, and with the support of his wife Teresa, sent her and their three children on to Burundi on an American convoy leaving the country, and stayed to face whatever came. He is credited with saving hundreds of lives as a result, including four hundred orphans who would have almost certainly been massacred if not for his intervention.

Car Wilkens joined me to discuss his decision, his sacrifice, and what he saw in Rwanda when the world abandoned them to their fate.

In 1994 when the genocide started in Rwanda, almost all foreigners left the country. You were a missionary at the time, and you didn’t leave. Why not?

Well we had been living there for four years, building schools, operating clinics, and building relationships, and when the plane was shot down and the embassy said that everybody’s going they said very clearly: No Rwandans. We’re driving south, and you cannot bring any Rwandans in your vehicles. If you bring Rwandans and we get to a road block, it will cause trouble. No Rwandans.

We had this young lady who lived and worked in our home and had been with us for three years. The kids loved her, my wife and I loved her, and she had a Tutsi ID card, which marked her as the enemy at that time. My wife and I talked, we prayed in the bedroom, and we said, we can’t just leave her and a young man (who was also a watchman) to be killed. So the decision started with those two people being right there in our house. And even though they never asked, it was pretty obvious to Teresa and I that we couldn’t just leave them there to be killed.

When you decided to stay, you obviously had to discuss this with your wife first. How did that discussion go?

Well honestly, it wasn’t a discussion about whether to stay or not. I think that was pretty much a given. The question was just how are we gonna do this. We had actually talked about the possibility of evacuation before, but when it came right down to it our conversation was more like: Two weeks maximum. This thing cannot last more than two weeks, and probably in two weeks you and the kids will come back and life will go on. It was right there in those final hours and then minutes—she made chocolate chip cookies for the kids and we were trying to make it as much like an adventure for the kids as possible, but I know when I helped her into the camper with the kids and said goodbye, it was a really heavy feeling in my heart.

Did the American embassy or any other foreign workers tell you to leave? Did they tell you that you were insane for staying?

Yeah. The consular officer, a really sharp young lady, she was just doing her best. There were about 257 Americans, and when I told her over the H/F radio that I was sending my wife and children and that I was coordinating the evacuation of a bunch of Americans—the folks at the dental clinic are coming to the ambassador’s home, I’m sending my wife and kids to the ambassador’s home—and she said, “What, wait a minute, what do you mean sending?” And I said, “I’m not leaving.” And she said, “No, you don’t have a choice. Everybody’s leaving.” So we had a little back and forth—we knew each other well and respected each other—and in the end she asked me if I would sign on a paper that I refused the help of the United States government to leave Rwanda and send that paper with my wife to the ambassador’s home, and so that’s how that conversation ended.

There were a couple of more attempts by UN soldiers to convince me to leave, but finally the Belgian commander who was taking the last of his Belgian troops out came by my house and I said thank you for your concern, but you’re actually putting your life at risk, your men’s life at risk, and you’re drawing unwanted attention to my house. Please, don’t come back here anymore. That was the final signing off of external pressure to leave.

And what happened then?

For three weeks we couldn’t get out of our house. The government announced a 24-7 curfew and nobody was allowed out on the streets, and so we were kicking into survival mode. We had to collect rainwater to get water, and I actually had invited another couple, a Rwandan pastor and his wife, to come to my home, and they had Hutu ID cards which meant they weren’t marked for extermination. It also gave us much more of a support group. She would buy stolen food over the fence, he was this incredible source of counsel and wisdom, so when the government did at the end of three weeks lift the 24-7 curfew and said if you had a legitimate reason to be out come to the city headquarters and get a travel permit—he’s the one at that time who said, Carl, if you want to do anything outside the house here, you’re going to have to build a relationship with the people in power.

So I started building relationships with people who [were in power]—most of them are in prison today or fled the country. The top guy I dealt with most of the time is serving a life sentence for genocide, crimes against humanity. But he’s the one who actually directed me towards two orphanages. When I came out I said, I’m here with ADRA and we don’t have much but we’re here to help. And it wasn’t like “he’s the leader of the killers,” it’s like he’s the mayor of the city and showing compassion and caring for the people of the city and he directed me to an orphanage where the greatest need was water. Little ones were being buried in the parking lot after dying from diarrhea. So I started the process of hauling water, finding a vehicle, finding containers, finding fuel, building relationships with whoever I could to get what I needed to bring food and water and medicine to what ended up being three groups of orphans around the city.

When did you realize that this wasn’t just a spasm of violence, but was turning into an actual genocide?

We knew right at the beginning that this was much worse than anything we’d experienced before. We had had some sporadic massacres—in one section of the country you’d have a hundred people killed, or in another section of the country you’d have fifty people killed—but now, with the shooting down of the plane, we’re on our high-frequency radio talking to every corner: An orphanage in the east, a hospital in the west, and everywhere—killing. So while we didn’t use the word genocide, but from the first day—before Teresa and the kids even left on the fourth day—we knew that this was something much, much worse than ever before and we knew it was directed against the Tutsis. So in effect you look back, and while we weren’t using the term, I think we knew it was everything that defines genocide.

Our hope was that the international community would respond. We had 2,500 UN soldiers, and so it was a real shock when all of a sudden we heard that the soldiers are leaving. I kept listening to the BBC every day thinking somebody’s going to do something, you know—America, the French, somebody—so that was the real [shock.] But calling it genocide—I don’t remember when we started using that word. I do know the media was using it in less than three weeks, but for me personally that wasn’t part of the vocabulary, although the intent was very, very clear.

You say that on the fourth day you realized things were getting bad. The fourth day after what?

The fourth day after the plane was shot down my wife and children left. But I would even say the day after the plane was shot down. People were being killed in our neighborhood, and I’m hearing reports from every corner of the country of people being killed. And then I talked to the Red Cross, on day three or four or five, in those early days, and the Red Cross was starting to confirm unimaginable numbers. When I finally got out after three or four weeks, the Red Cross was saying that over 200,000 [have been killed] and we find it nearly impossible to continue counting.

What sort of things did you see while you were in Rwanda?

The first day I went out, there was roadblocks all over the place. Ordinary citizens had been told you got to defend your neighborhood—drag a tree across the street, put some beer cases out there, whatever—make a roadblock, and start checking everybody’s ID coming through. When I came out after three weeks, it wasn’t like the streets had been lined with people who had been killed. Most of those had been picked up. There was an occasional body here or there. When I got to our offices, there was trash and garbage all over the parking lot, and in the middle of it—there was a corpse, and half of a leg was eaten off by our watchdog, who I guess had been surviving that way.

It was real chaos. You’d drive through neighborhoods and all kinds of things from the homes are drug out in the yard and are in the street. It was very chaotic on the one hand, and very structured in terms of roadblocks on the other hand. I remember seeing in the marketplace a man face down with a big radio boombox in each hand—I guess somebody had stopped the looting by shooting him. It was really, really horrible.

Did you see a confrontation between the Hutus and the Tutsis?

I came upon fresh massacre sites the day after they happened, and I guess the most memorable and the most tense and the largest confrontation, it was at the orphanage, the biggest orphanage with over 400 people where I was bringing food and water. I showed up one day and a gang of the Interhamwe [Hutu paramilitary organization] had given a warning the day before: We know there’s Tutsis hiding in here. Empty the place. We’re coming back tomorrow, and if this place isn’t empty we’ll kill everybody here, we don’t care if they’re Hutu or Tutsi.

Unbeknownst to me that threat had happened the day before I show up with water this particular day, toward the end of June. Within a couple of minutes all of a sudden these guys start materializing with their machine guns, with their machetes, but they stopped when they saw me. A two to three hour type of standoff followed, and eventually we managed to get a hold of some police who came, and that was even tough at that point because the guy in charge, the police officer, said look, you need to go and talk to my commander. We can’t spend the night, we’re too outnumbered here. And I didn’t know if he was just trying to get rid of me, because police were known to have been participating in the slaughter, so that was a really hard decision, to finally trust this police officer and go look for more help.

Things continued to get more bizarre. I ended up talking to the bogus prime minster. They had killed the prime minister, and the extremists had put in their own, and this guy, [Jean] Kambanda his name was, making a surprise visit to Kigali, the capital, and a secretary told me [to] ask him. It just seemed unimaginable that I ask him—he’s one of three guys in charge of the genocide—to stop a massacre. But he did. I asked him, and he stopped it, and a couple days later they moved those kids to a little bit safer place.

The key in this whole thing for me really came down to relationships. Whether it was a thief on the streets supplying me with powdered milk or whether it was the prime minister stopping a genocide, the biggest impact I was going to make was always going to be dependent on the relationships I was able to form.

How did you get the strength to see all the things that you did and do all the things that you did and face the people that you faced and talk to the people you talked to?

You look back at it and it is definitely overwhelming. There were days, situations—you know, my car is surrounded by eight guys with machine guns—and there’s so many moments that seemed impossible. But I think that having a mission, a pretty clear mission: Get food, get water to these kids, gotta get from Point A to Point B. You just did that one day at a time and you just put one foot in front of the other, and in terms of the heart and the head—nourishment or courage, there’s no doubt that for me my connection with my Maker. You saw courage in other people. My wife’s support and courage was invaluable. Little kids helping me clean barrels while snipers are shooting at us–[their courage] was an invaluable source of strength.

So while I believe that it comes from my Maker, I think you look around and you see it around you and that definitely is essential to not lose hope. Every night my wife and I had made a promise: We would read Psalm 34 together.

So you were in Rwanda for all 100 days of the genocide?

Yeah, we were living there for four years before and never left. On the fourth of July the Rwandan Patriotic Front drove these extremists, these genocidaires who were doing the killing, out of the capital. I was there. I can tell you stories about that day. And then I was there for another week to ten days while they cleared the rest of the country, and then came out and spent what ended up being seven months out with my wife and children before my organization felt safe for us to go back in. But then we were able to go back for a year and a half, which was a huge gift for all of us.

What things that happened during the genocide in Rwanda impacted the way you look at things now? You were a missionary before, but you were also the only Westerner present in one of the most brutal genocides in recent history. How did that change the way you look at things?

While I was the only American there in Kigali, there were five Catholic Sisters of Charity from Spain, and when you talk about sticking with people for better or for worse, these ladies were incredible. There was also a Frenchman, long hair, long beard—the kids called him Jesus—his name was actually Mark Vader, who stayed with a group of orphans. There was probably ten Europeans who stayed. I was the only American there. Their stories were hugely encouraging.

But we has foreigners had a certain advantage. There was a certain respect for foreigners—not an immunity, but definitely an advantage. Things that really astounded me would be like, the second night of the genocide when a gang came to our gate. We didn’t even know about it until the next morning because the neighbor ladies—ordinary, unarmed ladies—well, they were armed with stories, which are the most powerful weapons we have. But in any case, these ladies came and stood in front of the gate and said no to these guys who were—the ladies thought they would kill us. You see acts of courage in people who would be in other circumstances normal Rwandans. One of my co-workers had forty people in his home. The head of an orphanage showed that your tribe isn’t the important thing as his orphanage went from 80 kids to over 400, with some widows mixed in there.

I look at the stories and the experience of those Rwandans. Harry, down the street at another orphanage, who stepped up from being the watchman to being the director when the couple in charge evacuated. And I think to myself wow. There’s so many situations where you think you have to pick the lesser of two evils, but I think about that day with the orphanage being surrounded, and in the end I’m asking the prime minister to stop a massacre. We have just gotta hang on longer.

The lessons come afterwards, even to me. The way the Rwandans are recovering. The way that so many of them are not allowing the genocide and what they lost and what was taken from them to define them but how they’re focusing on what they have, just praying to God that they would have one family member that would survive. How they’re rebuilding after that. How they’re forgiving after that—the forgiveness stories out of Rwanda challenge anybody who hears them. If the people of Rwanda can do it in the most horrific of situations, surely we could be a bit more gracious.

Incredible man, and a great challenge to our dedication to people. Jaw dropping and humbling.