Blog Post

The Shoah: The murdered multitude and the righteous few

By Jonathon Van Maren

My introduction to this series on the 20th century, “The Century that Changed Everything,” can be found here. Part I is “The World Before the War”. Part II, “How the Great War transformed Western civilization–and is still with us today,” can be found here. Part III, “The Second World War: Saving Christian civilization from Hitler’s Reich,” can be found here. This column on the Holocaust is the fifth installment in the series.

In 1988, a special episode of the BBC programme “That’s Life” featured an extraordinary artifact: A scrapbook filled with letters and lists of the names of Jewish children saved by the Kindertransports, a rescue effort that brought thousands of children out of Nazi-occupied territory to England during the months leading up to the Second World War. The scrapbook belonged to Nicholas Winton, who as a young man had poured his efforts into getting children—at least 669 of them—out of occupied Czechoslovakia. When the Kindertransports ended with the German invasion of Poland, one of the volunteers gave Winton a scrapbook of the documentation, photos, parental letters, and press clippings as a gift. In 1987, Winton gave the scrapbook to Holocaust scholar Elizabeth Maxwell—her husband, Robert Maxwell, was a Czech Jew who had escaped the Nazis himself. She passed it on to the BBC. Winton was soon contacted by the BBC and asked if he’d be in the audience during a show on the scrapbook, and believing it was going to be just a few minutes, he agreed.

What followed was one of the most incredible moments in television history. As the 79-year-old Winton sat in the front row of a packed audience, the presenter read a name from the list of Jewish children saved on the Kindertransports: “Vera Diamant.” Vera is with us tonight, the presenter said with an enormous smile: “And I should tell you that you are sitting next to Nicholas Winton.” There were gasps as Vera, then a middle-aged woman, turned to Winton, grasped his hand, and hugged him tightly. Winton was overcome with emotion, rubbing tears from his eyes as Vera sat back, still clutching his hand. The man next to Vera had also been on Winton’s list, and leaned over to shake his hand. The woman sitting on the other side of him also turned to him: “I am another one of the children you saved.” She kissed him on the cheek.

His family, watching at home, were stunned. “We were a bit horrified by this” due to his age and the shock, his daughter Barbara told me. “The next week, he was invited back. In the meantime, there had been some publicity, so many of the children, who were in their fifties and sixties and hadn’t realized how they’d got to England, were reaching out to the BBC.” This time, on February 28, 1988, the presenter asked the audience a single question: “Is there anyone in our audience tonight who owes their life to Nicholas Winton?” There was a great stir, and the entire audience rose to their feet.

***

When Adolf Hitler was appointed the Chancellor on January 30, 1933, Germany had a Jewish population of 566,000. Most believed that his anti-Semitic ravings were merely the case of another populist politician engaging in the tried-and-true tactic of scapegoating to rile the mob, and that it wouldn’t amount to much beyond the odd business or journalist getting smashed up. But within months, the Nazis had opened Dachau, the first concentration camp, a holding pen for those who opposed them. Two days later, on March 24, the Enabling Act gave Hitler dictatorial powers. The Nazis staged a boycott of Jewish businesses just over a week later. Throughout 1934, more restrictions were passed on Jewish participation in civic life. And on September 15, 1935, the Nuremburg Race Laws were passed.

From there, things moved quickly. Jews were banned from many occupations and banned from most places. In 1938, following the Anschluss with Austria, Adolf Eichmann established the Office for Jewish Emigration in Vienna, while Himmler set up Mauthausen concentration camp near Linz. In July of 1938, delegates from 32 countries convened the Evian Conference in Evian, France, to discuss what should be done about the torrent of Jewish refugees desperate to escape the spreading shadow of the twisted cross. Delegate after delegate stood to offer their sympathies, but only the Dominican Republic agreed to offer the Jews asylum. The United States stuck to its quotas; the virulently anti-Semitic Canadian prime minister wanted nothing to do with the Jews; Australia noted that it had “no Jewish problem and no desire to import one.” The Nazis were triumphant. Despite all the sanctimonious criticisms of their treatment of the Jews, they noted, it was “astounding” that those same countries refused to allow the Jews in when “the opportunity [was] offered.” On the night of November 9, Kristallnacht—the Night of Broken Glass—would show the world that the Nazis meant business with an orgy of killing, synagogue burning, vandalism, and brutality. It was just the beginning.

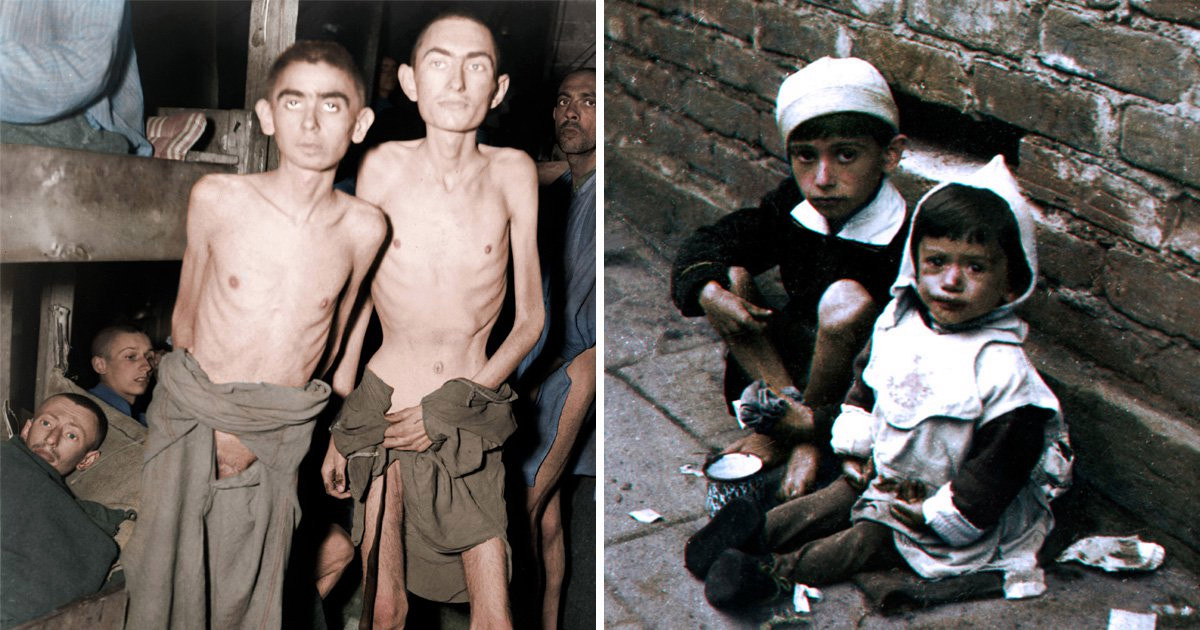

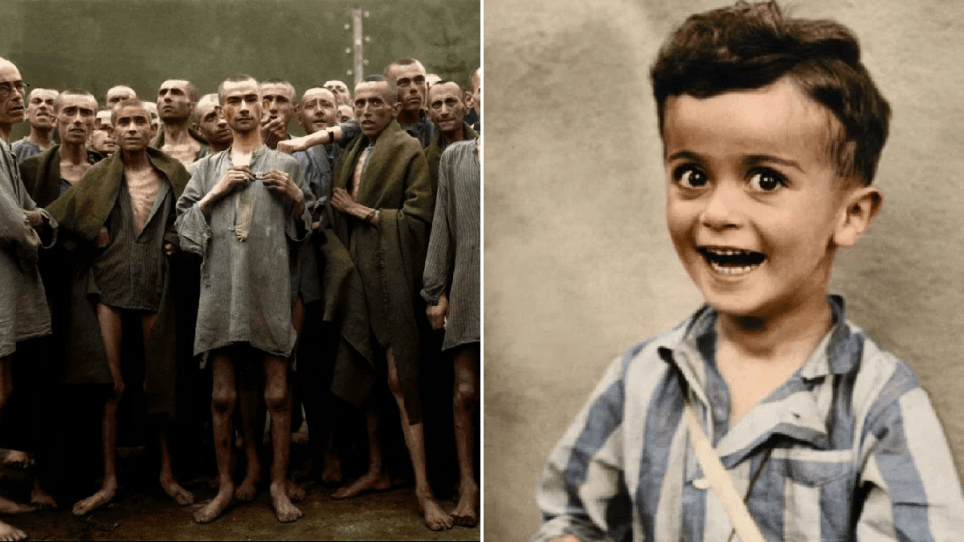

Abandoned by the world, millions of Jews were trapped on a continent rapidly being devoured by the Nazi beast. By 1945, the Nazis had set up 44,000 concentration camps, ghettos, and other prison sites and had killed millions of gypsies, Jews, political dissidents, Slavs, and other “undesirables.” The victims were shot in vast pits and trenches, gassed, hung, starved, beaten, and bombed. No death was too cruel, no child too innocent, no torture too inhumane. The depths of depravity were sought and found. The Final Solution was intended to be truly final. It is stunning to consider how close the Nazis came to realizing their master plan.

Among the murdered were six million of Europe’s 9.5 million Jews. It came to be known as the Shoah—Hebrew for “catastrophe”—or the Holocaust, a word derived from the Greek word holokauston, a translation of the Hebrew word ‘olah, which means “a burnt sacrifice offered whole to God.” The name was chosen by survivors haunted by the corpse-burning firepits and crematoria of the death camps.

***

I have always found there to be something surreal about hearing the stories of Holocaust survivors first-hand, as the horrors break free of the black and white images and documentaries and memoirs where we imprison them and come alive as the memories of a flesh-and-blood person sitting in front of me, somebody’s grandmother or grandfather. As we enter what Holocaust scholars are referring to as “the post-survivor era,” these first-hand experiences are becoming ever-more precious. Six million perished, but about 3.5 million survived to tell the world what it was like to live among the flames. Not many are left.

I’ve heard the stories of several Auschwitz survivors, but one—Frank Junger—has always stood out to me. He was fourteen years old when the Nazis arrived in the hometown of Valea Lui Mihai, Romania, and was used to anti-Semitism—the Iron Guard had already passed anti-Jewish laws. Shortly after the Germans arrived, Junger was deported to a ghetto in Hungary, and from there embarked on a journey through Dante’s circles of Hell: Auschwitz-Birkenau, Gunskirchen, Melk, and Mauthausen. It was there that he was finally liberated by the Americans 70 years ago in 1945.

Junger remembers the day the Germans arrived in March of 1944 vividly, the sound of their boots clopping crisply into his village. He was thirteen then, a skinny boy from a middle-class family, part of a Jewish community of 1,500 living in peaceful coexistence in a town of 20,000. According to his memory, his family owned at least 400 sheep and 40 oxen. But by the end of the month, they had lost everything, and the Jews of Valea Lui Mihai were sent to the ghetto in Hungary. In May, they were loaded onto a train with 120 men, women and children packed into cattle cars for a four-day train trip in excruciating heat.

“The trip was horrendous,” he recalled, his face alive with the memory. People were relieving themselves into a bucket as the summer sun slowly heated up the train cars. “It is something I can never forget. Some people went crazy, actually lost their minds, screaming, and kids were crying, they wanted water, they wanted food. There were infants.”

They arrived in Auschwitz at 4 AM on a Thursday, and an awful scene unfolded: Snarling dogs, barking guards, guns. Junger’s first view of Auschwitz was through a train window criss-crossed with barbed wire. The train doors opened, and the shouting started. Junger struggled for words to describe it all: Chaos, pandemonium, screaming. The families had thought they would get to stay together—wasn’t this a work camp?—but were pulled apart immediately. Men and women and children separate! They were herded before a cold, black-haired man “who I later found out was Josef Mengele, who they call the Angel of Death,” Junger remembered. “Inexplicable, a man like that. He was a PhD as well as a doctor, who performed medical experiments. I was a very scared little boy, thirteen and a half years old.”

Frozen in his memory is the last glimpse of his mother, after she was sent to the other side. She was holding tightly to the hand of a five-year-old child. He never saw her again, but that moment returned again and again. “The picture always comes back.”

The men were stripped and shaved from head to toe, and Junger remembers that everyone looked the same after that. The only thing they were permitted to keep was their shoes. The barracks were brutal: “No blankets, no pillow, no straw. The wooden planks, that’s it. Head to foot, like sardines. Somebody’s head was next to somebody’s foot. The food was liquid slop. We cupped our hands and tried to drink the food. As a kid, I was more easily adaptable. Some of the food fell on the ground and people licked it off the ground.” The guards laughed and mocked them: Look at the Jewish pigs, how they slop the food from the ground. But for most, humiliation was better than hunger. “If you haven’t eaten for four days and you haven’t been given utensils, how else could you manage? You can endure hunger much better than you can endure thirst. Hunger is in the pit of your stomach, but thirst makes your lips swell and your tongue. Unless you experience it—I don’t have words to describe it.”

All of that happened by Friday night. Frank had gone from home to hell in less than a week. Shortly thereafter, he was separated from his father, whom he never saw again.

Junger, however, was proficient in almost five languages: Hungarian, Romanian, German, Jewish, and a bit of Czech. “So I could understand a lot of what was going on, and understand the German guards perfectly.” There were no toilets or latrines, he recalled, but one barrack that was half-latrine and half wash station. As he was walking out of this barrack, a Polish man came up to him, grabbed him, and asked him how old he was. Thirteen, Frank replied. No, the Pole responded emphatically. If anyone asks, you say you’re 16. Why? Frank asked. Don’t ask questions, just listen to me, the man replied. Where are your parents?

Well, my mother went to the other side, and they said I was going to see her next weekend. My father they took away to work, Frank told him. The Pole, who spoke Yiddish, stared at him. “Do you see those flames?” he asked. “They are in heaven already.” Frank was stunned. What are you talking about, you’re crazy! No, the man replied. This is what’s happened. They select you, they take you to the other side, they gas you, they kill you, and then they burn you. Cremation. Frank had never even heard of cremation before—to burn a body was simply unheard of. He ran back to the barracks and told the others what he’d heard. They called him a liar.

Frank, on the other hand, decided to be as rational as possible. He ran through the number of barracks, and then the number of people who had arrived in Auschwitz with him on his deportation transfer. 6,000 people at 120 people per cattle car, by his calculation. Where would all those people have been put? “So there must have been some truth to what the man said,” he remembered. “Because there was simply no place to put all of the people that were coming in.”

Nearly 70 years later, Junger still recalled the daily routine clearly. “Up in the morning at 7’o’clock. At that point they gave you a cup of black, bitter coffee. I haven’t drunk coffee since then—I don’t like coffee. For lunch they gave you a bowl of soup.” At supper came roll call, and the meal was dispensed from loaves of bread, sliced into eight slices of no more than 2 cm each, and at times they got some limburger cheese, which was liquidy and spoiled. The whole meal, Junger noted, was no more than 450 to 500 calories. Thus, the average life expectancy of an inmate was about six weeks—even those who were fortunate enough to be selected to work. The work was about a kilometre away, carrying sod without wheelbarrows or any tools. “If you dropped it, you got clobbered,” he remembered. “If the piece of sod wasn’t big enough, you got clobbered. Life was very, very difficult.”

One Sunday, he recalled, two of the boys that were with him spotted their mothers as they were marching. “And here I was, all by myself. I don’t know how I survived.” One of the mothers came over, gave him a hug, and said “look after my boy, okay? I never forgot that.” To survive, Junger followed the advice of the Polish man who had given him the first warning to become as useful as possible, and so “became an apprentice of everything.” This was especially necessary as he was so small, and none of the camp authorities would take him to work in the businesses. In August, the Lodz ghetto was liquidated, and new inmates began arriving at Auschwitz. These people had been incarcerated since 1940, and according to Junger, 18-year-olds looked like shrunken children because of the three and a half years of malnourishment.

On Jewish New Year’s Eve, he recalled, the camp guards said they needed people to help pick potatoes and selected a few people for the task. They ended up in the barracks with the sickly, injured, and elderly people. “I knew right away what was going to happen,” Junger said. He had been selected after roll call, and he knew that the guards didn’t care where the bodies were, as long as there were the same number each morning. Some of the selected inmates began to pray, and Junger suggested that several of them rush the back door during prayers to get back into the general population. There were no takers, so the next morning he climbed out over the roof and got back into the general population. That night, everyone else was killed.

That was one of many close calls. When one of Junger’s friends got selected, he waited until the guard was distracted and yanked him back to the other side. He gravitated towards the healthy people rather than the weak and sickly to appear stronger. During one selection, they had to strip. All they had was a tunic-like shirt and a jacket—no underwear, no socks. Junger was very skinny, and had to walk in front of Dr. Josef Mengele for the second time. “He was a very good-looking man,” Junger recalled. “He was dressed in splendor. He had white gloves and his military uniform was absolutely spotless and he wore black riding boots. They were shining and polished to the point where you could almost see yourself in them. He had a stick. He always wore gloves.” Junger walked in front of the Angel of Death, clutching his clothes—and was selected. When Mengele’s back was turned, he scurried back to the right side. If he’d been caught, he reflected, he probably would have been beaten to death.

A week and a half later—incidentally, on the next Jewish holiday—there was another selection. Junger had saved a piece of beet peel he found in the slop and smeared it all over himself. When he was selected, he informed the doctor that he was a kitchen worker—and was sent back. “In October, there was an uprising in Birkenau,” Junger recalled. “One of the [inmate groups working at a] crematoria rose up. There was a factory there producing armaments, and the women were filling the armaments with black gun powder. The women stuffed black powder in their private areas, and there was two men working in the crematoria and accumulated the powder.” The revolt took place on October 7, 1944 after the Sonderkommando at Crematorium IV revolted, and nearly 250 prisoners died during the fighting. Another 200 were executed after the revolt was crushed, and the SS identified and murdered the five women who had been smuggling gunpowder to the prisoners several days later.

In November of 1944, a month after the revolt was crushed, Junger was taken from Birkenau to Auschwitz. Late in November, they blew up the crematoria. In January, he recalled, he was evacuated with other inmates by foot, a 120-kilometre march. During the march, he said, the guard would shoot anyone who stopped—even to relieve themselves. “Your guts and brains would be everywhere.” At one point, guards opened fire on the inmates, and Junger flung himself to the ground. A number of dead inmates toppled onto him. The only reason he survived, he said later, was the kindness of a friend who gave him long underwear—especially as the survivors were soon shipped by train to Mauthausen. It was a bitter irony, he noted, that Jews were shipped in closed cattle cars to Auschwitz in May in the brutal heat, but in open cars through the Carpathian Mountains in the dead of winter. Out of the 140 people packed into his train car, Junger estimates that only thirty survived over the icy four-day journey.

As the Americans hammered in from the West and the Russians advanced from the East, the prisoners were often on the move and desperation made the guards particularly brutal. One old man, Junger recalled, was shot just because he talked. Junger was actually afraid for the war to end—he was certain he would be killed before that happened. “I didn’t think they would allow anyone to be left alive who had witnessed what went on.” On May 5, the guards began to flee. Junger followed suit, heading into the woods around mid-day. Around four or five o’clock, he came to a road, and thought the best thing to do would be to lie down and wait for dark to cross. Some German jeeps came pounding past, and he crouched in the fetal position. They flung a grenade in his direction and kept driving. A mere half-hour later, the Americans came down the road from the same direction. Junger remembered them clearly in their fatigues, and he emerged from hiding to show them where the camp was.

He then headed east, back to where he’d come from. He got about ten kilometres before he caught typhus. He wasn’t sure how long he had it, and by the time he recovered, he scarcely remembered how to speak or who he was. He headed back to his family’s farm, and tried to work it. It was impossible, and nobody would work for a 14-year-old. Of the 1,760 Jews in his community, he discovered, only 56 had survived. His parents were not among them—only two uncles had survived, and he lived with them for a time in Budapest. In 1948, Communism arrived in Hungary, and Junger decided that there was no future for him there. A survivor organization had asked him where he wanted to go if his family had perished, and he’d told them either Canada or America. He headed to Hamilton, Canada, where he worked for an automotive company until his retirement in 1995. In 1962, he married Eliane Ligeti, and they had two children. He now spends the time he has left telling his story.

His story is one out of millions.

***

How did this happen? How were millions of God’s Chosen People, the Jews, murdered in the heart of Christian Europe? The answers to that question are legion, and far beyond the scope of this simple essay. Daniel Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners is a compelling read on that subject, and the history of European anti-Semitism also does much to explain the backdrop of what occurred. For the purposes of this essay, I simply want to draw our attention to what happened—and how some responded. Because in the midst of catastrophic collective failure, there were those—many of whom have now been designated by the State of Israel as “Righteous Among Nations”—who did extraordinary things to save their neighbors. To reflect on their example is to force a re-examination of our own lives. Contrary to what many of us believe, most of us would not have done the courageous thing (a subject I examined in a recent column for the Times of Israel.)

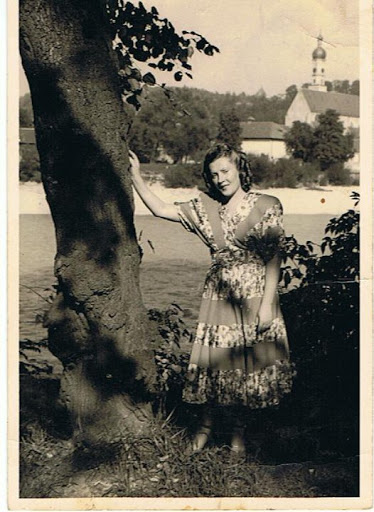

Many of the Holocaust rescuers remained silent about their deeds—and the price they paid—for years. One of them was Irene Opdyke, a well-known Californian interior decorator. It was decades after the war, in the 1970s, her daughter Jeannie Smith told me, that she finally heard her mother’s story. The family was eating dinner when the phone rang, and her mother answered it. It was a college student doing a survey on Holocaust denial. At first, Jeannie told me, she didn’t really notice what her mother was saying: “You generally ignore your parents while they are on the phone.” But as the conversation stretched on, she realized her mother was telling an incredible story. “When she hung up the phone that night, I remember her looking at me and saying, ‘All these years I have kept silent, I have allowed evil to win. If we don’t start talking, history can repeat itself.’”

Irene was born in Poland in 1921 to a strong Catholic family, and her dream was to become a nurse. She was in nursing school in 1939 when the Germans and the Russians invaded. She joined the Polish army with several other nurses, working as a partisan in the forest. “She was caught one day by Soviet soldiers who gang-raped her and dropped her off at a Russian hospital,” Jeannie told me. “She became a prisoner there.” Later, Irene was able to return to Poland on an exchange and was put to work in a munitions factory supplying the German front. The work conditions were brutal, and one day she passed out in front of a German major due to the fumes. The major asked if the blond and blue-eyed Irene was German, but when she replied that she wasn’t he appreciated her honesty so much he gave her a job working in the kitchen, serving German soldiers.

The atrocities Irene witnessed shook her to her core. One day, her daughter told me, Irene found herself running  errands. There was a crowd of people milling about, from elderly folks to pregnant women and newborns. Children were screaming: Mama! Mama! She saw an SS officer yank a baby from a mother’s arms, throw it in the air, and shoot the child. “There is always a moment,” Jeannie noted, “where a choice is made.” Irene later recalled that she then “realized that God gave us free will to be good or bad. So I asked God for forgiveness and said if the opportunity arrived, I would help these people.”

errands. There was a crowd of people milling about, from elderly folks to pregnant women and newborns. Children were screaming: Mama! Mama! She saw an SS officer yank a baby from a mother’s arms, throw it in the air, and shoot the child. “There is always a moment,” Jeannie noted, “where a choice is made.” Irene later recalled that she then “realized that God gave us free will to be good or bad. So I asked God for forgiveness and said if the opportunity arrived, I would help these people.”

“She said nothing was ever planned out,” Jeannie told me. “You stumble across some way to help and you just did it until the next thing came along. That’s also how you build courage. Courage is like a muscle, and using it is how you make it strong.”

Irene’s opportunity came soon thereafter. When the German major she worked for was transferred to Ternapol, another Polish town, he took Irene with him. She met Jewish people working in the Gestapo laundry room and became fast friends with them. Her unique position gave her access to vital information: One night, while serving German officers their dinner, she heard them making plans to raid the ghetto. She quickly relayed the information on to her friends in the laundry, and they passed it on to the Jews in the ghetto. Many were able to escape. Soon thereafter, she overheard more plans—this time to wipe out the entire Ternapol ghetto. This meant that her friends in the laundry room would be murdered. But how could she save them?

“Then,” Irene recalled later, “a miracle happened. About three days later, the major called me and said, ‘I have a villa and I want you to be my housekeeper.’ I knew then that could be the place I would hide the Jews. They stayed in the attic when the major was downstairs and in the cellar when he was upstairs. Then we had a real problem to deal with. One couple was expecting a baby and we knew the child would cry and make too much noise. They said they’d give up the child, but I said, ‘Ida, please wait, don’t do anything. We’ll see—you’ll be free.’ Then one day in the middle of the marketplace they hanged a Polish couple with their two children and a Jewish couple with their little child. They forced us to stay and watch to see what happened because there were signs on every street corner saying they would do that if you helped Jews. I ran home to my friends. Three of my friends were in the kitchen and I was so shaken that I forgot to leave my key in the lock after I locked the door. This was the way I would protect us from the major coming in unexpectedly. We were talking and all of a sudden, the major was standing in the kitchen. He was looking from one to another, trembling, and he didn’t say one word. He went to his library.”

Sick with fear, Irene followed him. The major was furious, screaming, demanding to know how Irene could have betrayed his trust by hiding Jews under his nose in his own house. “They are my friends!” she cried, kissing his hands, clinging to his knees, begging. He gave Irene a price: He would allow her and her friends to live if he could rape her while they hid in his villa. She had no choice. Irene endured her own personal hell for several months—until the Germans began to lose, and she was able to flee with her friends into the forest. Soon after, the Russians arrived. “On May 4, 1944, a little boy was born in freedom,” she recalled. “That was my payment for whatever hell I went through—seeing that little boy. His name was Roman Heller.”

Irene joined the Polish partisans, hoping to find her family. Her father, it turned out, had been shot, and her mother had died of a stroke, and she would not be reunited with her sisters until the 1980s. She ended up in a displacement camp for Jewish people, and was interviewed by a man from the United Nations, sent to the camp to help the refugees settle in Allied nations. The American heard her story and told her that the United States would be proud to have her. In 1949, she headed to the America, alone. “As she stood on the bow of the ship heading into Ellis Harbor, she put a sign across her memories: Do not disturb,” her daughter told me. “And she left it.”

She settled in New York City, first sewing in a union shop, and later working for a Polish-Jewish woman. One day, five years later, she went to the UN to have lunch in the cafeteria. A man walked up to her. I know you, he said. His name was William Opdyke, and he was the man who had interviewed her in the displacement camp in Germany all those years before. He asked her out to dinner, and they were married six weeks later. Two years after that, in 1957, they had a daughter: Jeannie. A decade and a half later, Jeannie listened in shock as her mother told the story she had never heard to a college student she had never met on the phone—and committed to telling the story to whoever would listen.

Despite all that had happened to her, Irene was filled with thankfulness for the life she had been given. She passed away in Fullerton, California, on May 17, 2003. “The night before she passed away, I remember sitting on her bed,” Jeannie told me. “She said how absolutely grateful she was about her life.”

***

Not all Holocaust rescuers survived to tell their stories. Men and women like Nicholas Winton and Irene Opdyke, and more famous figures like Oskar Schindler and Corrie ten Boom eventually became revered for what they had done. Countless others, like the nameless Polish couple with their two children that Irene saw hanging next to their Jewish neighbors they had done everything to save, were murdered for their efforts. It is essential for us to remember, as we look back, that what the Holocaust rescuers did was extraordinary—both because a minority of people pursued this path of resistance, and because of the potential cost of doing so.

The first time I visited Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial, I stumbled across a powerful sculpture as I wandered the grounds, reading the name plaques on the trees in the Garden of the Righteous Among the Nations. The large, solemn face of a bearded man with sorrowful eyes was framed by a cluster of small children, his hands clutching them to himself in an act of paternal protection. His name, I discovered, was Janusz Korczak. In 1911, he became the director of Dom Sierot, an orphanage for Jewish children. He ran a newspaper for children, wrote books on the right of children to safety and respect, authored children’s stories, and sought to care for his orphans and inculcate the values of truth and respect in them—even against a rising tide of anti-Semitism.

In 1940, Korczak’s orphanage was forcibly moved into the Warsaw Ghetto by the Nazis. Repeatedly, Korczak was offered shelter and hiding places by Polish friends and the underground on the “Aryan side,” and repeatedly, he refused. He could not and would not abandon his children, he would say. Despite his own failing health, he and his colleagues went relentlessly from door to door, seeking food, medicine, and warm clothes for his children. Even when it became clear that to stay with his orphans would mean death, he would not leave them. When the Germans came for him and his 192 orphans, he led them to the trains himself. According to Ghetto eyewitness Joshua Perle: “Janusz Korczak was marching, his head bent forward, holding the hand of a child, without a hat, a leather belt around his waist, and wearing high boots. A few nurses were followed by two hundred children, dressed in clean and meticulously cared for clothes, as they were being carried to the altar.”

The scene was also described by Władysław Szpilman in his book The Pianist:

He told the orphans they were going out into the country, so they ought to be cheerful. At last they would be able to exchange the horrible suffocating city walls for meadows of flowers, streams where they could bathe, woods full of berries and mushrooms. He told them to wear their best clothes, and so they came out into the yard, two by two, nicely dressed and in a happy mood.

Some eyewitnesses reported that when Korczak, the orphanage staff, and the children reached the Umschlagplatz, Korczak was recognized by an SS officer as the author of a favorite children’s book and offered him the chance to escape, while others indicate that he was instead offered preferential treatment that would have required him to be separated from the children. Whatever the case, Korczak refused, and on August 5, 1942, he climbed aboard the train to Treblinka with his children and thirteen other members of his orphanage’s staff. He was never heard from again. All were murdered in the maw of the death camp.

Polish poet Jerzy Ficowski later penned a poem titled simply with the date of his death—5.8.1941—and the subtitle “In Memory of Janusz Korczak.” It describes the last hours of Korczak and his children:

What did the Old Doctor do

in the cattle wagon

bound for Treblinka on the fifth of August

over the few hours of the bloodstream

over the dirty river of time

I do not know

what did Charon* of his own free will

the ferryman without an oar do

did he give out to the children

what remained of gasping breath

and leave for himself

only frost down the spine

I do not know

did he lie to them for instance

in small

numbing doses

groom the sweaty little heads

for the scurrying lice of fear

I do not know

yet for all that yet later yet there

in Treblinka

all their terror all the tears

were against him

oh it was only now

just so many minutes say a lifetime

whether a little or a lot

I was not there I do not know

suddenly the Old Doctor saw

the children had grown

as old as he was

older and older

that was how fast they had to go grey as ash

***

As the Allied forces smashed their way into Occupied Europe, the discovery of the death camps would stun the world. Decades later, secret documents would reveal that the Allied Powers had been aware of the unfolding genocide at least two-and-a-half years earlier than originally known, and that as early as December 1942, the UK, the US, and the Soviet Union had been made aware of the fact that two million Jews had already been killed and that at least five million more were also at risk of being murdered. War crime charges against Hitler, Himmler, Hess, Frick, and von Ribbentrop, among others, were already being drawn up. Despite this, very little was done to curb the Holocaust at the time, and the shock of Allied commanders indicates that they were utterly unprepared for what they found.

Many of the top Nazis escaped justice. Hitler shot himself in the mouth after taking cyanide, and Himmler made do with a poison capsule. The Nuremburg Trials were set up to hold the Nazi regime accountable for their crimes against humanity, and ten prominent Nazis—including Wilhelm Frick and Joachim von Ribbentrop—were hung, while others, including Hess, were dealt a range of prison sentences. The vast majority of those who perpetrated the Holocaust, however, escaped any punishment—including Josef Mengele, Auschwitz’s Angel of Death. Holocaust survivor and Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal spent decades tracking down war criminals, most famously tipping off the Mossad to Adolf Eichmann’s presence in Argentina. Eichmann, the architect of the Final Solution, was abducted by Israeli intelligence services in 1960, put on trial on live TV, and executed for his crimes in 1962. Wiesenthal’s efforts resulted in the prosecution of hundreds of Nazis, including notorious death camp guards and perpetrators from New York City to Brazil.

In 2014, I interviewed the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s top Nazi-hunter Efraim Zuroff, who was then launching Operation Last Chance, the final push to see aging war criminals brought to justice. He urged those who felt sympathy for the fragile, elderly Nazis to see them not as the aged men they are now, but as young men in their prime, using their strength to murder men, women, and children. Currently, a 93-year-old former SS guard who served at the Stutthof death camp near Danzig, Bruno Dey, is on trial in Germany, where he has been charged with assisting in the murder of 5,230 people. He was 17 at the time, and so is being charged in juvenile court. Last December, a 91-year-old survivor of Stuthof, Abraham Koryski, testified against Dey from Israel. He was 16 when he arrived at Stutthof, and he recalled the horrifying displays of sadism put on by the SS, including one instance where they forced a son to beat his father to death. Dey admits to knowing about Stutthof’s gas chambers, but denies guilt for the atrocities perpetrated there. Dey’s trial is expected to be among the last of the Nazi war criminals, as both the surviving perpetrators and eyewitnesses slip one by one into eternity.

When the last of those who witnessed and experienced one of history’s greatest evils leave us, it will be up to us to remember not only the victims of the Holocaust, but also how and why it happened. We will need to remember that those who risked everything to save Jews during the Holocaust were exceptional because they were the exception. To understand the 20th century, we must understand this crucible of history, where most of humanity failed and a few lit up the darkness like flaming torches of unspeakable courage and virtue. There is much to learn, and we have only just begun.