Blog Post

How one child survived the Holocaust because of his mother’s incredible sacrifice

By Jonathon Van Maren

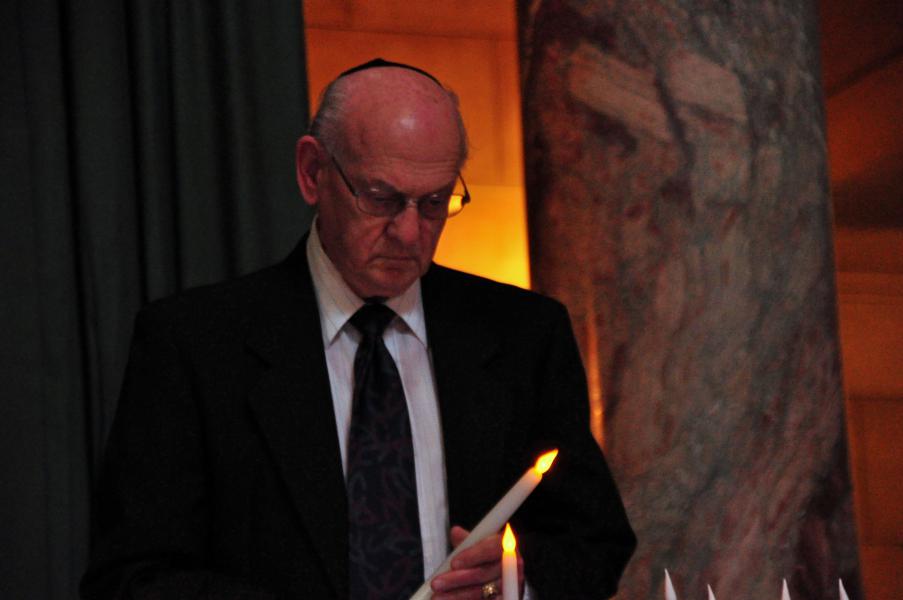

For decades, all Fred Kader could remember was that his life began in a Belgian orphanage. He knew he was born in Antwerp on July 20, 1938; he knew that his parents were dead. He could remember the excitement amongst the orphans and the staff as Allied planes growled overhead on their way to Germany to unleash hell. He remembered the staff talking about the Nazi retreat and then, suddenly, a moment of quiet just before the armistice. One by one, children in the orphanage began to leave—picked up by family or friends of family. Soon, Kader recalled, “We were left with just a few of us. Even the staff left. We ran around the streets and did what 7-year-olds do.”

For a half-century, Kader told me by phone from his home in Omaha, he lived with the mystery of a lost past. In 1947, a gentleman showed up at the Wezembeek, the Jewish orphanage, and informed Fred that he was his uncle and took him home. After years of feral freedom, it was difficult. “They tried very hard to give me a home and to make a new life for me, but I wasn’t used to living in a family anymore.” Once, of course, he must have lived with a family. “But I had no recollection of that.” His uncle did his best to turn Fred into a “mensch,” and finally, one day, told him it was time to talk about Fred’s parents.

He and Fred’s father Jacob had been seized by the Nazis as slave labor in 1942 and sent to Calais to work on the Atlantic Wall defences, setting mines. They worked until they wore out like broken tools, and then they were put on a train to Auschwitz. The laborers had heard, even at that early date, that “at the end of the railway line was death.” Desperate prisoners would leap from the train, and the Germans would shoot at them and return with dogs to track and kill escapees. The train carrying the Jeruzalski brothers (Kader’s original name) went from France, stopped in Belgium to swallow more prisoners, and then carried on.

In those days, Kader told me, they were still using regular trains with runners between the cars for transports—the cattle cars were yet to come. Fred’s uncle hunted for his father from car to car, but to no avail. Then, as the train approached the border, he finally gave up, and leapt from the train alone. He fled back to Brussels, found his family, and “survived by living underground in a farmer’s field,” a dugout under the shacks where they stored their goods. He hid there until the end of the war with his wife and two children. After the war, he bumped into a social worker who was stunned to see him alive. He told her he’d lost his brother and that his brother’s family was probably dead, too.

“The lady said, I’m not sure you’ve lost everyone,” Kader said. “She knew of a child with a very similar name in an orphanage. Frans was my Flemish name as a child; when she mentioned my name, he knew that I was alive. This is how he came to get me.” They never again discussed the war or his missing parents. In 1949, he left Europe for Montreal to live with a great-aunt. Initially, he again struggled to live with a family—but most of his aunt’s children, five sons and a daughter, were already married with children, and his aunt had the patience of Job. She worked hard to make something of him, and Fred adopted the name Kader from her. As he made his way through grade school and high school, he realized that some people truly did care.

Kader didn’t spend much time agonizing over the past; he had a future to build. He changed his name from Frans to Francois; when he realized that Canadian Jews lived with the Anglos rather than the French, Francois became Fred. In 1960 at the age of 21, he decided to become Canadian. He got in touch with the Jewish Immigration Service, which miraculously tracked down his birth certificate. Accompanying that was a letter with the names of his family members. His father was born in March 1896 in Poland. Jacob’s first wife was Kader’s aunt, with whom his father had produced his half-sister Rachel, born in 1920 in Germany, and half-brother Felix, born two years later. In the early 1930s, the family left Germany for Poland, taking Kader’s mother with them. When his aunt died, his father married her younger sister—Kader’s mother. They’d had a son named Fignas in 1933, Paul in 1935, and then Frans in 1938.

Kader asked himself: If his mom and dad were alive, what would they want him to be? And the answer was simple: a mensch, a decent human being. He headed to college, won scholarships, and got into medical school. He became a doctor because he wanted to help people. “Children who survived the war tend not to have a big mouth and become lawyers. You have a tendency to be seen and not heard.” He wanted to help children—“if I hadn’t gotten help I would have been up in smoke like the rest of my family in Auschwitz”—and so became a pediatric neurologist. On a visit to Seattle to visit cousins, he met a beautiful girl with a big smile named Sarah and married her. They had three children together. Eventually, he ended up working at the university in Omaha.

Throughout it all, Kader never knew how he’d survived the Holocaust. One day, speaking with his colleague, the children’s psychiatrist Tom Jaeger who had also been a hidden child in Belgium, he decided to search for the truth. Jaeger persuaded him to attend the First International Gathering of Children Hidden During World War II in 1991 in New York City. Kader was then 52, and steeled himself for disappointment—there was no guarantee he’d find anything. Fifteen hundred people showed up from around the world. “Everyone put their names up on boards, looking for someone they knew,” he told me. Kader found the organizers and asked them if there was anyone who knew anything about orphans from Belgium.

The organizers directed him to Sylvain Brachfeld, who had published a book chronicling the hidden children of Belgium only three years before in French—the English translation of the title was “That they did not get all of the children.” Kader found Brachfeld and introduced himself. The journalist stared, and then began pointing at him. “I know exactly who you are. I know how you got saved from the train to Auschwitz, and how you survived. I even know which page I wrote about you in my book.”

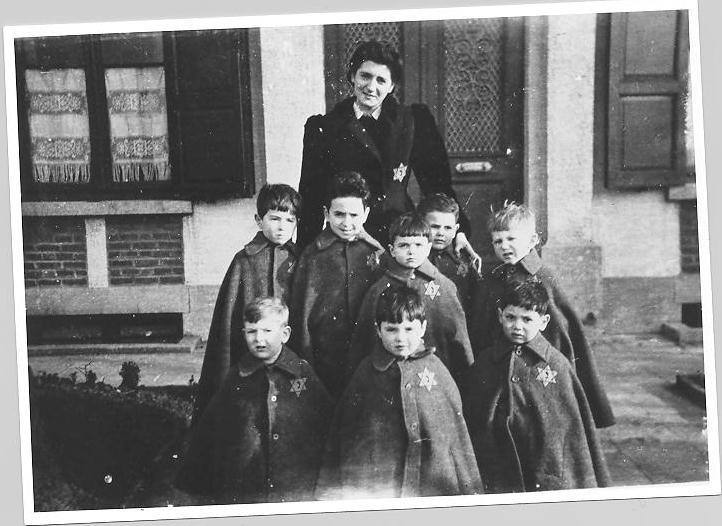

The Belgian Queen Elizabeth, Brachfeld told him, had declared that all children under the age of sixteen were under her protection, and the Nazis had used this as a pretext to set up orphanages—that way, they would know where all the children were. The moment they turned sixteen, they could ship the kids off to Auschwitz, eliminating the next generation of Jews. Predictably, the Nazis began to get impatient. On October 10, 1942, they ordered the eight staff of Wezembeek to get the fifty-eight children ready for a train trip—and they didn’t need to pack any things.

At the train station in Antwerp, other Jews—including four-year-old Kader and his mother—were also awaiting deportation. Kader was a little blond-haired, blue-eyed boy, and standing at the station, his mother realized that her son would have a better chance of survival if she forced him to walk away. She told her son to leave and start walking. The little boy wandered off. He has no memories of his mother; only of wandering through the streets of Antwerp. He knows that she was with him moments before this; that this must have been heartbreaking; that she did this because she loved him. But he cannot remember what she looked like, what she smelled like, or what her voice sounded like as she pushed her little boy away from her to save his life. He has never found a photograph of her.

He was discovered by a nun, who whisked him off to a house near the city called the Home of the Good Angels, where five other children were hidden as well. The house was raided, and Kader and the others were once again sent to a railway station for deportation, this time in Malines. It was at this train station where the orphans of Wezembeek were awaiting deportation. However, the trains were delayed—and Kader later discovered that this was because these were the very trains carrying his uncle and his father, and they were late because captives kept leaping from the cars. Belgian rescuer Madam Marie Albert Blum, meanwhile, was hard at work taking advantage of the delay. She was part of a child-saving network that constituted an underground network of safe houses throughout Belgium, and she began bribing German officers to let some of the children go. Blum secured the release of some orphans—and Kader, discovered by the orphans huddled in one of the barracks with several other children, came with them.

These revelations, Kader told me, stunned him. “I’m standing in front of this guy telling me how I survived the war.” He bought the last copy of Brachfeld’s book, and “then I walked around in a daze for a little while.” Then he found another man who had information. When he explained who he was, “this fellow turned white as a ghost and nearly fainted—he had to be caught and lowered into a chair.” The man’s name was Marcel Chojnacki, and he was the orphan who had found Kader huddled in the barracks near the train station. When Blum negotiated their release and the children climbed into a truck to leave, four-year-old Kader was petrified and had to be held by a ten-year-old. It was Chojnacki’s lap that he sat on as they drove back to Wezembeek.

As Chojnacki spoke, Kader remembered. “Out of the blue, it came back to me. It was pitch black, it was thundering, lightning. It was a storm, the noise was incredible, and there was a clanging on the truck. So that was quite a day. I found out how I ended up in the orphanage, and how I survived the war.” It is surreal for him to consider, even all these years later. As he waited to be shipped to Auschwitz while Blum negotiated his release, “my dad is on the way to his death, not knowing I am on the other side of the wall being saved.” The two may have been very close to one another, heading in different directions.

Kader tracked down the Nazi deportation lists, and there he found the names of his father, his mother, his siblings, and his uncle, who had escaped. Another puzzle piece clicked into place when he discovered that his uncle had not been on the same train from Calais as his father—which is why his uncle had not been able to find Jacob as he plunged up from car to car, searching for his brother. He found a note stating that his mother was deported on September 12, 1942. Only the name of his half-sister Rachel is missing. “She must have fallen off the face of the earth. There is nothing on her anywhere—not even the Red Cross could track anything down.”

Kader began to put together the pieces of his past. He attended Hidden Children of Europe conference in Brussels, and went with his wife to meet Mrs. Blum, the hero who had saved his life. Many years later, he went to see the memorial to the Jewish people sent to their deaths in Brussels. “Sure enough, my whole family is listed there, including my half-sister, although what happened to her nobody knows.” His cousin suggested they go to Auschwitz to say the mourner’s Kaddish, and they chanted the ancient words at the end of the railway lines where life stopped and hell began. After visiting the camp, they returned to Brussels, and something extraordinary happened.

“My cousin’s wife comes running out and says, I just spoke to your aunt about Fred and Sarah being here and she says she has to talk to you,” Fred told me. They got into the rental car and headed to the aunt’s home. There, they found an elderly couple in their nineties awaiting them. They had numbers tattooed on their forearms. Both had survived Auschwitz and then returned to Brussels after liberation. The old woman began speaking in Yiddish and crying. Kader cried as he told me the story. “I was at the train station with your mother and you in 1942 when we were waiting to go to Auschwitz,” she told him. He and his mother had been standing next to her, the woman said, and his mother had turned to her and said: “Look at my son. He looks more Aryan than the Nazis. He needs to get out of here.” She turned to her son and said: “I want you to walk out of the train station and don’t look back.”

“And I did,” said Kader. “No questions asked. I got up and walked out. My mother went to her death never knowing that I survived.” Based on everything he’s read and everyone he’s talked to, he knows that he must have been with his mother from between 9:12 AM to 10:31 AM on September 12, 1942, before he walked away and was picked up by a nun when she spotted the gold star sewed to his clothes. He was one of the fortunate few—4,500 children were hidden in Belgium during World War II, and up to 90% of the “hidden children” joined the “helping fields” afterwards, becoming doctors, nurses, and therapists. “So,” Kader told me. “I finally put it all together.”

I had been incredibly honored that he was willing to share so much with me, but the old man was thrilled to speak about his lost family and how he found them. I thanked him for his time. Kader paused.

“Thank you for listening.”

I am speechless. These stories need to be told in school. This history is very important.