Literature, Reviews

The Enduring Power of Shakespeare: 400 Years After the First Folio

In October 2023, Dame Judi Dench appeared on Graham Norton’s talk show with a clutch of other celebrities—but she wasn’t there to make small talk. She was there to talk about her first love. Her memoir of her life with the Bard, Shakespeare: The Man Who Pays the Rent, was published on November 8. Shakespeare, she informed the audience, is always in our heads—even when we don’t realize it. We quote him all the time by accident. “If I just poke you with a stick, could you do a bit of Shakespeare for us?” Norton asked Dench. “I’ll do a sonnet,” she replied, and the audience hushed as she recited Sonnet 29:

When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries,

And look upon myself and curse my fate,

Wishing me like to one more rich in hope,

Featured like him, like him with friends possessed,

Desiring this man’s art and that man’s scope,

With what I most enjoy contented least;

Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising,

Haply I think on thee, and then my state,

(Like to the lark at break of day arising

From sullen earth) sings hymns at heaven’s gate;

For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings

That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

Cheers, applause, and whistles followed. Comments on the video from young people ran along the same lines: “I didn’t think I liked Shakespeare—but this!” Four centuries after his death, the great playwright can, in fact, still pay the rent. As one commentator observed: “England is like a dementia patient with these brief, delicate moments of self-recognition.” That is precisely right: these flashes of recognition render people awed and breathless as the magnificence of our Western heritage, so often maligned and sneered at by the termites who now infest our institutions, comes into view. Despite what you’ve heard, the West really was a great civilization. Have you read Shakespeare?

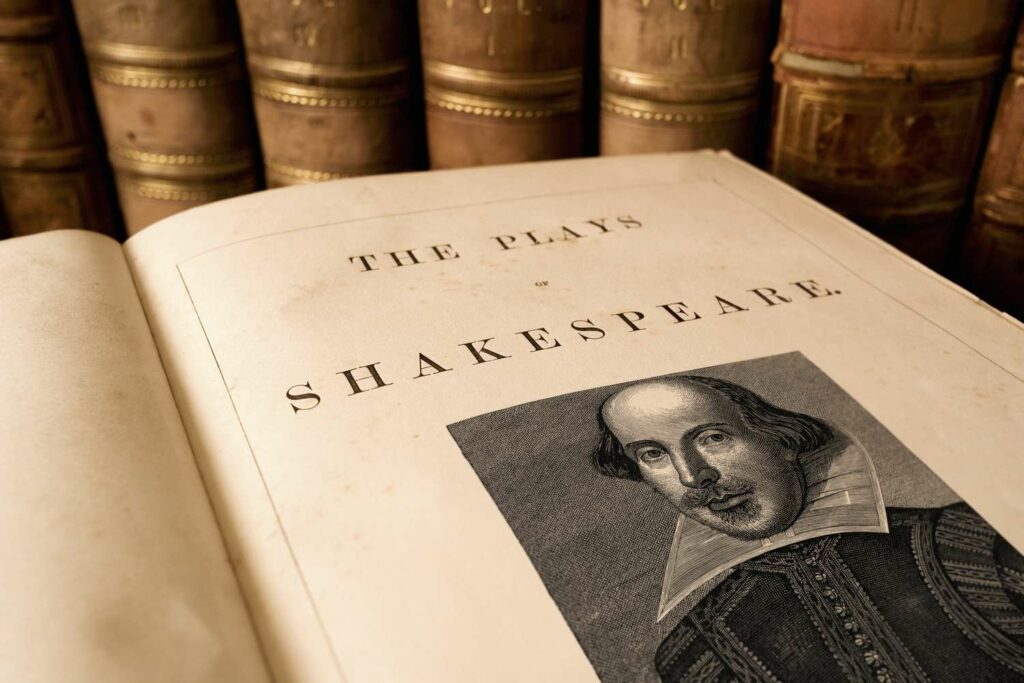

Four hundred years ago, in 1623, Shakespeare’s plays were collected into a book titled Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, known to us today as “the First Folio.” Published seven years after Shakespeare’s death by two colleagues, the First Folio stands unrivalled as “the greatest literary work ever created” according to Shakespeare: Rise of a Genius, the BBC’s new three-part documentary series created to celebrate the anniversary. About 750 copies were published of which around 235 are accounted for, with two discovered as recently as 2016. It was in that year that I first saw one of the original First Folios, on loan to Florida International University from the Folger Shakespeare Library, which hoards 82 of them. In 2020, a copy sold by Christies fetched $10 million, making it the most expensive work of literature ever auctioned.

Together with William Tyndale and the King James Bible, no person or work has done more to shape the English language than William Shakespeare, and the scale of his achievement is staggering. He produced Othello, Macbeth, and King Lear in a single year, rendering rage, love, melancholy, lust, and ambition with extraordinary skill. “Who has ever done it better?” Dame Judi Dench asked the camera, shaking her head. “I wish I’d met him. Oh, I wish I’d met him.”

Famously, we know relatively little about him. In 1582, he married Anne Hathaway when she was 26 and he was only 18. They lived in the small, rural town of Stratford-upon-Avon, three days’ travel from London. Three children arrived in short order: first Susanna, then the twins, Judith and Hamnet. Shakespeare was 23 when Queen Elizabeth came to power in 1587 and, like so many writers, he left for the city in order to make a name for himself. He was an intelligent young man hemmed in by circumstances: due to his father’s debt, young William’s education had remained incomplete. The actors interviewed in Rise of a Genius are, unsurprisingly, sympathetic to the “passion” and “blind madness” that drew Shakespeare away from his family and into the pages of history.

READ THE REST OF THIS COLUMN AT THE EUROPEAN CONSERVATIVE