Historical Essays, The Sexual Revolution

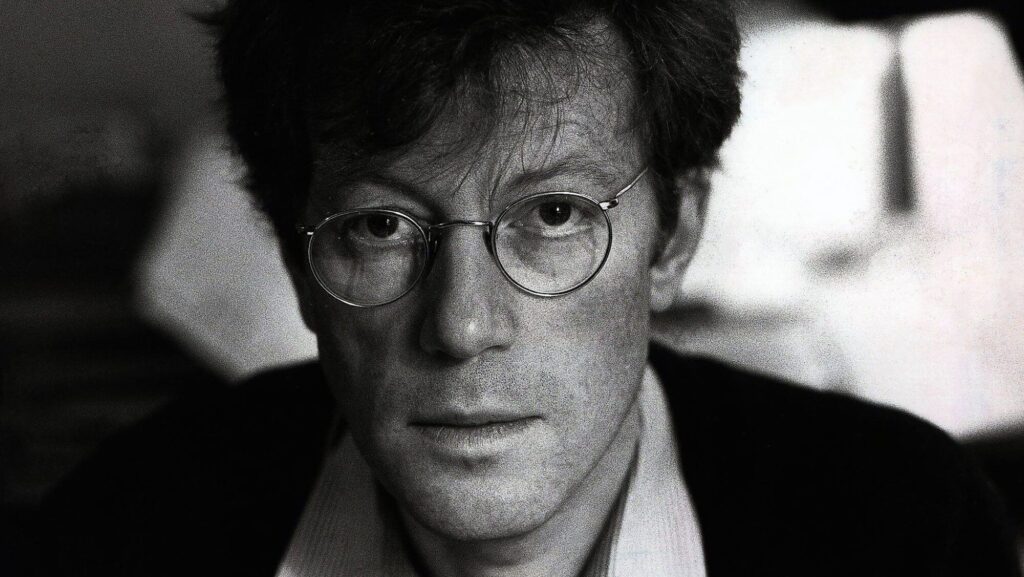

Sir Roger Scruton Against the Sexual Revolution

This essay was first published on January 12 at The European Conservative. Social media won’t let me post it due to Canadian law.

In May 1968, a 24-year-old Roger Scruton watched from an apartment window in Paris as the streets below him roiled with rage. Students were screaming, throwing cobblestones through plate-glass shop windows, pulling down lampposts, and overturning cars. Policemen arriving on the scene were pelted with stones; Scruton saw one officer drop to the ground, grasping his face as blood streamed through his fingers. The riots, which had begun with a demand by students to be able to have sex with one another in their rooms, had come to encompass a host of social causes. Their slogan perfectly summarized the demands of the sexual revolution, then spreading like wildfire across the West: Il est interdit d’interdire! (It is forbidden to forbid!)

The students scrawled other graffiti on the walls, as well. “Climax without hindrance,” read one. “The more I make love, the more I want to start a revolution. The more revolutions I start, the more I want to make love,” read another. The counterculture may have popularized the slogan “make love, not war,” but the riots in America and across Europe revealed that they were more than willing to initiate both.

It was watching the riots that made Roger Scruton a conservative. “I was disgusted by it,” he told me shortly before his death in 2020. “I thought there must be a way back to the defence of Western civilization against these things. That’s when I became a conservative. I knew I wanted to conserve things rather than pull them down.” Scruton became one of the revolution’s fiercest critics, publishing scores of books that may make him, one critic noted, the only conservative who is still read a hundred years hence. But despite the best efforts of Scruton and his allies, the revolution which smashed the moral framework of an entire civilization was entirely successful—perhaps beyond the wildest dreams of the rebels rampaging through Parisian streets a half-century ago.

Four years ago on January 12, 2020, Sir Roger Scruton died, bequeathing us a body of work covering a breathtaking array of subjects including the nature of beauty, architecture, conservation, hunting, England, and literature. He made his own literary contributions, as well—I’ve often wondered why his viscerally powerful novel on the counter-revolutionary movement in Czechoslovakia, Notes from Underground, is not widely recognized as a masterpiece (although it did receive justly laudatory reviews). I know few young conservatives who have not been informed or inspired in some way by Scruton’s life and work; for me, his valiant resistance to the sexual revolution and the intellectuals who spawned it have been invaluable.

Scruton understood that the street battles unfolding in 1968 had begun in the academy, and that in addition to activism and politics and traditional living, the fight would have to be taken to the intellectuals. Indeed, copies of Wilhelm Reich’s book The Sexual Revolution: Towards a Self-Regulating Character Structure, which advocated for the breakup of the natural family and the sexualization of children, had been hurled at police in Paris and the similar uprisings in Berlin, and students scrawled Reich’s name on walls. To understand the student rioters, one had to understand Reich and other revolutionary intellectuals. In the years that followed, few engaged them on their own terms as eruditely and intelligently as Scruton.

Nearly fifty years after witnessing the sexual revolution surge to the surface of society during the heady street riots of 1968, Roger Scruton wrote a reflective essay on all that had transpired. Our institutions, he observed, have been largely destroyed, the old morality has gone, and “the result of the sexual revolution is with us for all to see … far more alarming and far more devastating for the next generation” than anyone predicted at the time. In his conclusion, he mused about where we might be heading:

The promised pleasures have staled, showing us that it was in any case not pleasure that we wanted. Vestiges of the old morality reappear—the growing panic over pedophilia; the new attempts to control what happens in schools and universities; forms of sex education that now emphasize “stable relationships” rather than “good sex.” Whatever else these new developments show, they remind us that human beings remain as they were—creatures hungry for love and commitment, who have as great a need to give as to take, and who are looking for the forms of social life that make love and giving possible. Will they find these things again? And if not, will they be able to do what until now they have always done by instinct, which is to make a lasting home for their children, and teach those children to make a lasting home in their turn?

That is the task before us. Scruton’s counterrevolutionary struggle is over, and it is up to us to pick up the torch and carry on the fight for goodness, truth, and beauty that he fought so well for so long. His memory is a blessing.