Literature

The Lost World of Sterling North’s Rascal

It was a hot, humid morning when we reached the Sterling North Home and Museum in Edgerton, Wisconsin. It was, in fact, the perfect day for a boy and his raccoon to head out to a cool creek for crayfish and trout. A brown metal sign, purchased by the children of the town many years ago, stands on the front yard in front of the white frame house with the wraparound porch: “In this home in 1918, 11-year-old Sterling North lived with his ‘ringtailed wonder’ pet raccoon Rascal.”

Rascal: A Memoir of a Better Era is the sort of book that sticks. I first read it in Grade 7 and have wanted a baby raccoon pretty much ever since. I have a small etching of Sterling and Rascal fishing signed by North with “greetings from Little Rascal” in my library (it’ll have to do). On reading it to my children last year, I realized that the book is more than merely a good story—it is a great American novel, easily on par with lesser works that get far more attention.

Published in 1963, Rascal sold over 2. 5 million copies, was adapted for film by Disney and launched a 52-part TV series in Japan that resulted in racoons being inadvertently introduced into the country. Children imported up to 1,500 coons a year and triggered an ongoing ecological crisis as the new species thrived and promptly did what these bandits do: happily plundered the country. After a decade of this, Japan belatedly banned their import; a 2024 headline affirmed that the country is still “grappling with an invasive racoon population” that costs millions in damages annually.

format(webp))

Rascal begins with Sterling’s discovery of an abandoned baby raccoon in the forest outside Brailsford Junction (his fictional name for Edgerton). Between May of 1918 and April 1919, Sterling wandered the woods around Lake Koshkonong, built a canoe in the living room, read books in the branches of the huge tree in the backyard with Rascal lounging in the branches, and reveled in what would be the last year of his boyhood. One never knows until they are over that the good old days are ending; Rascal is both an adventure story and a requiem for childhood.

But in Edgerton, much still is as it was. The original barn stands; the phrase “Damn Kaiser Bill,” carved into the siding by Sterling as his brother Herschel fought the Germans in Europe, is still faintly visible (the volunteer guide, Betty, emphasized to the children that both swearing and vandalism are unacceptable, however understandable the historical sentiment). The highchair where Rascal tried to eat his sugar cubes—he would wash them, they would vanish, he would hunt desperately—sits by the back door.

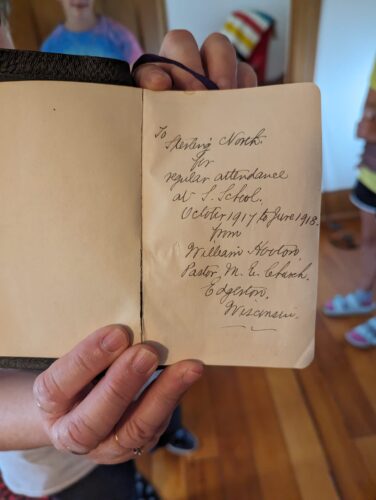

Rev. Hooten’s Methodist Church can be seen from the barn; it is easy to see how the smell of Sterling’s alarmed pet skunks reached the windows one hot summer day over a century ago and drove the congregants from their pews, forcing the kindly pastor to end his sermon early for the first time anyone could remember. From the backyard, you can also see the steeple and bell tower of the church where Poe the Crow stashed his hoarded treasures, including Sterling’s sister Theo’s stolen engagement ring. His little Bible, given to him by Rev. Hooten for regular attendance at Sunday School, is displayed inside the museum.

Sterling’s initials are still inside the barn, placed there with the same green paint he used on the 18-foot canoe that he built indoors, much to the horror of his visiting sisters. The Society set up a Christmas tree fronted by chicken wire, just as Sterling had it. The cleats nailed to the side of the house for Rascal to access his bedroom via the second story window are gone, of course—the house passed through several owners before a fundraising campaign was launched by the children of the town to purchase it and preserve it as a museum in 1992.

Sterling North went on to become a journalist, working for the Chicago Daily News (alongside Carl Sandburg, the great poet and Lincoln biographer), the New York World-Telegram, and the New York Sun. He married his high school sweetheart Gladys Buchanan, and they had two children, Ariel and David. After going freelance, North wrote a series of American biographies for children and several novels, including So Dear to My Heart and The Wolfling, his final book before he died in 1974 at the age of 68.

I very much enjoyed his 1966 adult wildlife memoir, Raccoons Are the Brightest People, although my relationship with raccoons has been more fractious than North’s lifelong non-aggression pact. Several people I know have had pet baby coons, much to the delight and fascination of my children. They are smart, lively, and adorable. But I had to fight a growing horde of them during one weeks-long springtime war in which coons attacked my quail, pheasants, and chickens and had to be repelled with traps and bullets.

I connected with Sterling’s daughter Ariel North Olson, who is now 93, by email, and she sent me some reminisces she penned about her father for the 25th anniversary of the museum. “Some of my earliest memories are of lying in bed at night, hearing the clickety-clack of typewriter keys down the hall,” she recalled. “While I drifted off to sleep, my dad was hard at work on whatever book he was writing…But somehow, he still found time for us. I have wonderful memories of the stories he told to me and my brother. The ones we liked best were about Rascal, the pet racoon he had when he was a boy.”

Sterling North was deeply suspicious of change, both as a conservationist and in some ways, an instinctive conservative. He despised comic books and dubbed them a debased genre of entertainment. Perhaps this is why he subtitled Rascal “A Memoir of a Better Era,” which was nostalgia for lost boyhood as much as anything else. “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there,” as L.P. Hartley wrote. When he died, the sort of childhood he experienced was still possible and not yet colonized by the omnipresent screens that suck the souls of children into the digital wilderness to be scarred by lurking pornographic horrors.

It was sad to hear that the annual Sterling North Literary Festival is discontinued because too few people were showing up, another casualty of the comorbidities of Covid and growing disinterest in books. Rascal, Betty told us, is considered too difficult for many children now. Fans of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ classic The Yearling have recently expressed similar dismay that her work may be forgotten. But Rascal, like The Yearling, has the power to capture generations anew not just because of the power of the prose, but because they hark back to a time when the outdoors was not just the natural habitat of racoons, but of children, too. A better era, perhaps, but not yet irretrievable.

Thank you for another great book recommendation! I am a grandmother now living in Alberta and I read all of Jim Kjelgaard’s books after reading about them on your blog. I bought a hard copy of Rascal and Kjelgaard’s Chip in the hopes my adolescent granddaughters might find them as enjoyable as I have. What a refreshing change from most of the current genre for young readers.

I read most of your articles and columns and I appreciate all your insights on the current state of our culture but am also grateful to learn of these uplifting books that I can turn to when it feels like the world has gone completely mad.

That’s great!

Jonathon, it was such a pleasure meeting you and your family and it’s great to see that you shared this information about RASCAL with all of your followers. I hope that they get a chance to read Sterling’s story and that they will enjoy it as much as you do! Your support is greatly appreciated.

Thank you, Betty!