Blog Post

With Jonathan Edwards in Massachusetts

By Jonathon Van Maren

I was sitting in a sushi bar in Northampton, Massachusetts, scrolling through my Facebook feed when I stumbled across a headline from the scathing Christian satire news site, The Babylon Bee: “Mainline Protestantism Declared A Safe Space For Those Offended By The Gospel.” It included a painfully accurate, barely-hypothetical joint statement from a number of Protestant denominations: “We are in agreement that there is a great need for churches to rise up and create safe spaces that are safe for questioning and accepting our identities, doubts, fears, failures, and blatant sins. Effective immediately, we are declaring all mainline Protestant churches safe spaces, where there are no judgements, conviction, repentance, or gospel presentations whatsoever.” I chuckled painfully and showed it to my wife. She made a face.

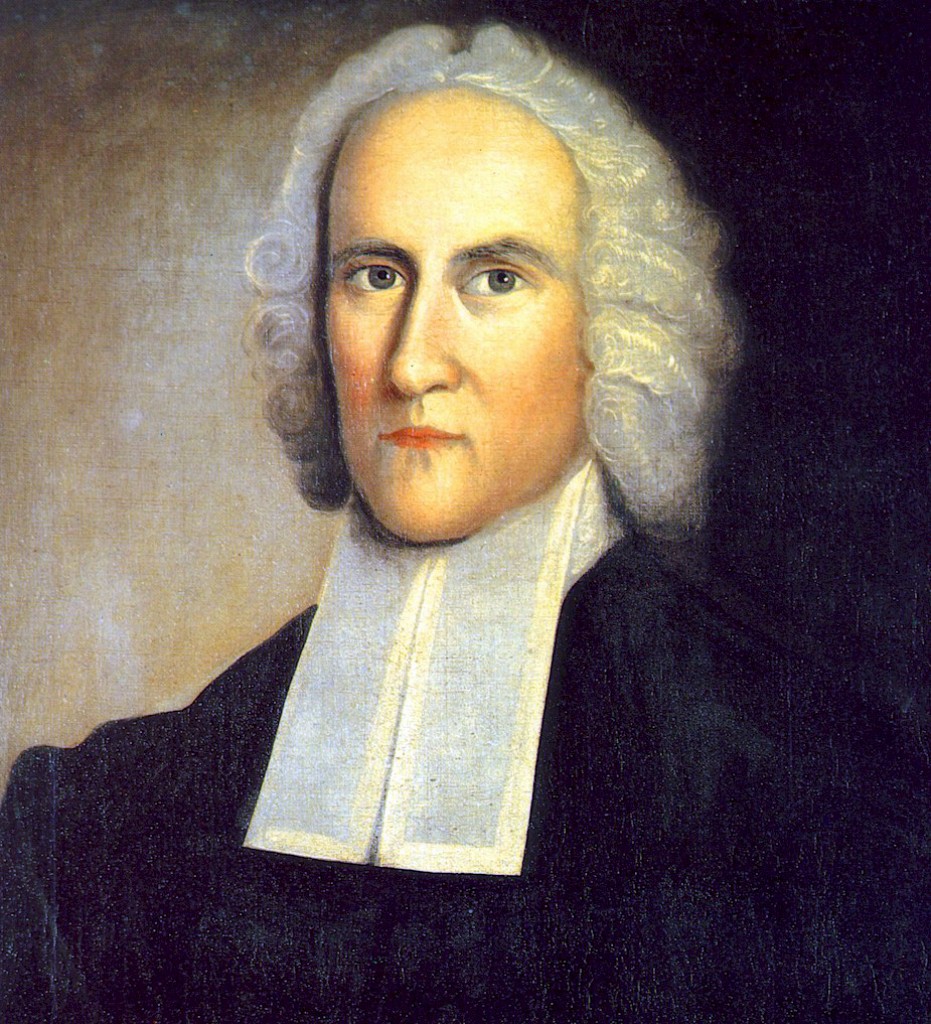

We were driving lazily across the eastern United States on our honeymoon, and had decided the day before to drive to Northampton to see the site of the Great Awakening of 1734-5, when the fiery preaching of the brilliant theologian and philosopher Jonathan Edwards had been used to spark a widespread revival of Christian faith. Some of his sermons are still read in American universities—not for their spiritual insights, but for their searing imagery. Every time I think of his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” one line always leaps into my mind: “There are the black clouds of God’s wrath now hanging directly over your heads, full of the dreadful storm, and big with thunder.”

We had arrived in town around 3 pm, and the air was hot and sluggish. It was a typical New England town—old buildings, rows of shops, beautiful aging churches, and people strolling about as if they really had nothing else to do. The first thing I noticed is that the gay rainbow flag was hanging everywhere: On shop windows and other business establishments and even on houses. As Charmaine and I walked up the street to visit one of the old churches in Northampton, we found a large plaque describing Edwards as “the stern Puritan who preached fire and brimstone sermons such as his notorious ‘Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.’” Notorious? I hadn’t quite expected to see such an obvious bias on a landmark plaque.

When we took a closer look at the old church building, the reason for the bias became immediately clear. Identified by a large white sign as one of the “First Churches,” the cinder-stone building also featured a giant rainbow flag stretched across the lawn. Planted there by the United Church, which was apparently using the space at the moment, the flag declared, unironically, that “God is still speaking.” Perhaps He is, but these days it doesn’t appear that the United Church is much interested in listening.

Another United Church across the street, which boasted sculpted reliefs of the Great Awakening and Jonathan Edwards on the granite wall outside and portraits of Edwards and his wife Sarah inside, also prominently displayed evidences of their allegiance to the Sexual Revolution. For the life of me, I couldn’t figure out why post-Christian denominations would want to boast any affiliation with a “notorious” Puritan and his family. The six-color rainbow flags stirring here and there in the wind about town seemed almost taunting. God created the rainbow to assure mankind He would not destroy a wicked world with a Flood ever again, but it seems that we are still determined to wave that symbol of His goodness as our symbol of defiance to tempt Him.

It was a short walk to the Forbes Library, which boasts one of the largest collections of Edwards manuscripts and secondary sources, and incidentally doubles as the Calvin C. Coolidge Presidential Library. The receptionist called about for someone to let us into the reference room, and a middle-aged, sandy-haired fellow named Dylan let us into a dimly-lit room smelling gloriously of aging leather and old books. He pointed us to a bookcase covered in dust and cobwebs. It didn’t appear as if many people were particularly interested in the Edwards Collection at the moment. When I took one book off a top shelf, the front cover fell off with a small puff of dust. Many of the first editions, dating back to the 1700s, had been carelessly labeled by librarians in felt pen or whiteout.

Dylan hovered in the background, chatting with us. He seemed enthused that someone cared about the very ill-cared-for collection of books he’d been entrusted with. More and more, he told us, the people that come to Northampton wanting to see the site of the Great Awakening and visit places associated with Jonathan Edwards are actually Christians from South Korea. In Northampton itself, he said, people don’t really care for religion anymore. When Charmaine pointed out that there were a lot of churches around, Dylan chuckled ruefully. “Sure. But nobody goes to them anymore. The churches in town aren’t really descended from Edwards or associated with his theology. This town has changed.”

I began to pay closer attention to the bumper stickers driving about as Charmaine and I finished our walking tour. Bernie Sanders 2016. Embrace Diversity. Obama-Biden 2012. Co-Exist. Aside from the artfully-placed remnants of Jonathan Edwards’ original house, landmark plaques noting where his church had once stood, and dubious memorials set up by churches that despise his theology, not much was left here of the Puritan titan and his legacy. South Koreans, it seems, are far more likely to read his works for spiritual insight than modern-day North Americans.

Before we left town to head to Plymouth, Charmaine and I drove through the black wrought-iron gates of an ancient, decaying cemetery on the edge of town. Many of the gravestones were cracked or had fallen over. The faint inscriptions, often dating back to the 1700s, were eroded by centuries of weather. The ground slumped where coffin lids had rotted through and collapsed, and even the more recent asphalt had given up resisting nature and shrugged up tree roots along the path. On the edge of the graveyard stood the Edwards plot, reading the names of his children and a number of his descendents. Many of the names had faded away, but by brushing the grass away or running our hands over them we could read the names: Mary, Timothy, Lucy, Sarah.

The tour pamphlet I’d gotten at the information centre noted that Edwards’ last words, to his daughters Lucy and Esther, were for his Sarah: “Give my kindest love to my dear wife, and tell her that the uncommon union which has so long subsisted between us has been of such a nature as I trust is spiritual and therefore will continue forever.”

As our car bumped back down the grassy path out of the graveyard, I remembered a poem I’d read in a cemetery a long time ago. It wasn’t written by Edwards, but it seems like something he would have said:

Think of me as you pass by,

As you are now, so once was I.

As I am now, you soon must be.

Prepare yourself, and follow me.