Blog Post

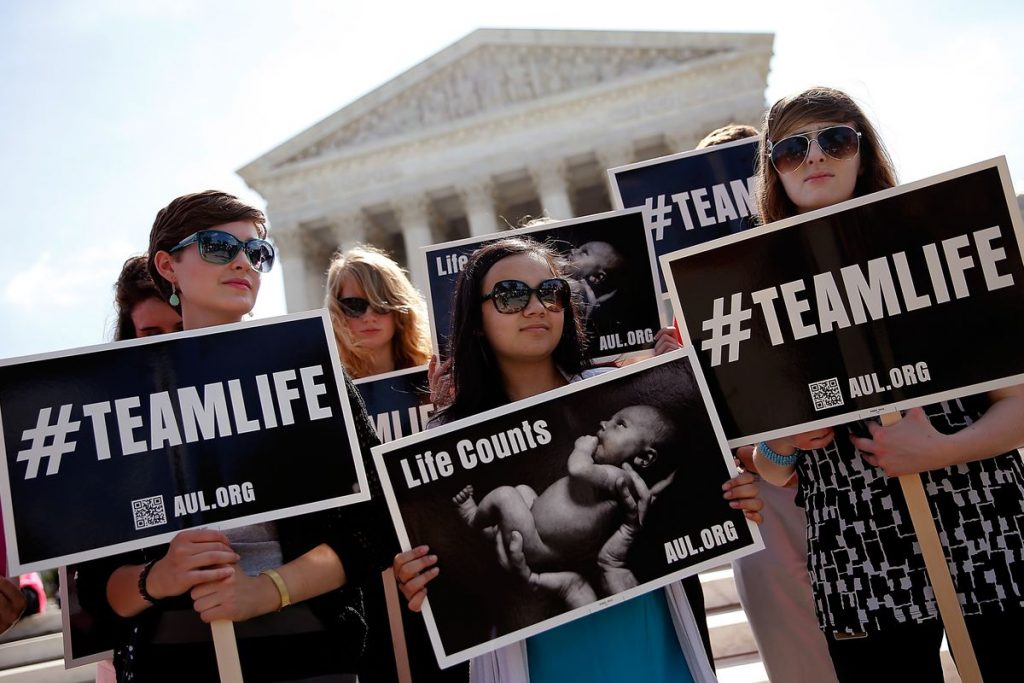

The “pro-birth” lie: How the pro-life movement is preparing for a post-Roe world

One of the most common slanders leveled against the pro-life movement is that we care only about children prior to birth. Nearly every mainstream journalist I’ve been interviewed by has asked me some variant of that question, almost always in an accusatory tone. This convenient deceit, of course, has been long-debunked (like most pro-abortion arguments), most notably in an extensive essay published nearly a decade ago by The Public Discourse titled “The Lazy Slander of the Pro-Life Cause.” The title almost captures it—the slander is of the movement, rather than the cause. Abortion is wrong regardless of whether pro-life activists, individually, are hypocrites.

Incidentally, a short stint in the pro-life movement would highlight for any of these curious journalists just how willingly self-sacrificial most ordinary pro-life people are. Many activists—and I could name them, but they’d be furious—have taken pregnant women into their homes when they needed a place to stay, adopted supposedly “unwanted” children, and put in long volunteer hours to stand up for children they will never meet. People have told us that when we are doing pro-life work on the streets, we have their permission to give their contact info to any woman considering abortion with the promise that they would happily adopt any child. And this is not exceptional behavior in the pro-life movement—in my experience, it is the norm.

I’ve always found the oft-shouted criticism that pro-lifers are “pro-birth, not pro-life” to be sort of weird, anyhow. Of course we’re pro-birth—we want every baby to be safely born. Guilty as charged. Are our opponents claiming that they are not pro-birth? That would seem to hit a bit closer to the truth than they are usually willing to get. Yes, we are pro-birth and we are pro-life, and because we are pro-life we are specifically anti-abortion. We seek to build a society where every child is welcomed as a blessing rather than treated as an unfortunate consequence.

Which brings me to a fascinating article by Emma Green in The Atlantic earlier this month, titled “The Anti-Abortion-Rights Movement Prepares to Build a Post-Roe World.” To her credit, Green lays out behind-the-scenes efforts going on within the American pro-life movement to prepare for a world where many more mothers will need assistance as abortion becomes increasingly rare, and possibly even illegal. The former CEO of Popeyes, apparently, is assisting in the effort. Give it a read—it really is a fair and well-researched story:

As activists move closer to their goal of making abortion illegal, they have started planning for the infrastructure needed for a world with more babies—and recruiting major CEOs to bankroll their cause.

In most circles, abortion does not make for polite dinner-table conversation, especially if you happen to be running a billion-dollar global franchise. So for years, Cheryl Bachelder kept quiet. She stood out professionally as the rare female CEO of a major corporation, overseeing Popeyes while chasing after three daughters and, eventually, four grandsons. As a Christian, she watched with distaste as her fellow business leaders indulged the decadence and money-fueled antics of the 1980s and ’90s, posing on magazine covers with jets and girls. She and her husband donated to candidates for political office whom they knew and personally trusted. But because she oversaw a large, publicly traded company, Bachelder mostly kept her views on one particularly controversial issue secret. “If I go to lunch with a good friend, and they find out I’m pro-life, I can tell you the look on their face,” she told me. “‘You’re kidding me. You are an educated, CEO woman and you’re pro-life. What’s wrong with you?’”

Recently, Bachelder has become captivated by what will happen if the anti-abortion-rights movement succeeds in its goal to make abortion illegal in the United States. “What if there were a lot more God-given babies, and we were, as a community, completely unprepared to help their mothers?” she said. Now that she’s retired, Bachelder is willing to speak publicly about her views on abortion—our conversation was the first time she had spoken with a journalist for a national news outlet about her involvement in the anti-abortion-rights movement.

Activists in that movement are working towards a grand, and perhaps fantastical, vision: a world where abortion is not just illegal, but unthinkable, and where babies are much more common as a result. This future has felt more tangible since the election of Donald Trump, who appointed two justices to the Supreme Court, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, who are skeptical of the constitutional right to abortion laid out in Roe v. Wade. With Ruth Bader Ginsburg, one of the staunchest defenders of abortion on the Court, recently hospitalized and going through a new round of chemotherapy, it’s possible that abortion rights will face an existential challenge within the next few years. Anti-abortion-rights activists realize that this moment of triumph will require planning—and infrastructure. “The magnitude of that question is huge,” Bachelder said. “I think it’s fair to say every community is unprepared to answer that question today—probably hasn’t even thought about it.”

She has long believed that life begins at conception and that death is “God-ordained” and should not be invited early with assisted suicide or other kinds of interventions. She and her husband have donated to faith-based organizations that provide pregnancy support and attempt to direct people away from abortion. But she nevertheless worries about getting into “the mud-throwing conversations of politics,” she said. “We actually work on solving things, in the business world. We don’t have any time to yell and scream and throw things.” She longs, in other words, for association with an anti-abortion-rights movement that is apolitical, even though abortion is one of the most politically charged topics of our time.

Late last year, Bachelder attended a fundraiser hosted by the Susan B. Anthony List, or SBA List, the anti-abortion-rights organization that has arguably had the most influence over Trump’s judicial appointments and voter outreach on this issue, at a home in Sandy Springs, Georgia, a tony city north of Atlanta. She and a group of friends, mostly other business leaders, were there to brainstorm all the community support systems that would need to be stronger in a world where abortion is illegal: mental-health services, addiction-recovery programs, affordable child care. Many of their proposed solutions didn’t touch the messy business of politics. One woman even suggested that they consider taking pregnant women into their homes. Wow, Bachelder said to herself, I haven’t thought about that. Along with other members of this group, Bachelder agreed to financially back an SBA List test program in Georgia called PLAN—the Pregnancy and Life Assistance Network—that would compile and publicize resources already available to women dealing with unplanned pregnancies, modeled after a version of the program in Northern Virginia. In theory, it’s an ambitious effort to find common ground between hard-core anti-abortion-rights activists and people who want to help pregnant women but may not be convinced that abortion should be completely banned.

Marjorie Dannenfelser, the head of the SBA List, brought White House-branded Twizzlers and a commemorative plate along to the gathering—spoils of her success in Washington. “We believe we are coming much closer to a different kind of world, where Roe v. Wade is either unrecognizable because it’s been chipped away or it’s overturned and laws start to flourish in states that reflect the will of the people who live there,” she told me. Over the past year, the SBA List’s research organization, the Charlotte Lozier Institute, has undertaken a massive effort to look at the state resources available to pregnant women and children, including housing, medical centers, income limits for Medicaid, and more. This served as a foundation for PLAN, which is still in its early stages. The project—imagining the “beatific vision” of a post-Roe world, as Dannenfelser put it—is partly pitched at people like Bachelder who oppose abortion but shy away from partisan battles. “A lot of donors, a lot of people in the evangelical community, a lot of breathing human beings just hate politics right now,” Dannenfelser said. She spends her days in the “roughest area” of politics, she added, fighting over a controversial issue in tightly contested elections. “My dream, and my belief, is that at the heart of the pro-life movement, there is not that dissonance” of political opposition.

There is an inherent tension in an anti-abortion-rights project designed to rally social services for women, no matter how ostensibly apolitical it may be. Over the past two decades, the anti-abortion-rights movement has aligned itself almost exclusively with the GOP, which generally favors cutting government funding for housing, food stamps, and other programs that support poor women and children. No group has solidified this partisan alignment more than the SBA List, which pours money and manpower into supporting Republicans in competitive races. As Democrats more aggressively pursue the expansion of abortion rights, the SBA List sees the Republican Party as its only viable ally, at least at the national level.

Bachelder envisions a future stage of the PLAN project in which policy makers would do a version of the “gap-planning analysis” that businesses use to anticipate what customers—in this case, pregnant women—might need. But getting there, to a place where most anti-abortion-rights legislators would also champion the expansion of social services, would require a massive political realignment. Although a post-Roe world has seemed more possible than ever lately, it’s also a ways off.

This summer, the anti-abortion-rights movement suffered a major defeat at the Supreme Court, when Chief Justice John Roberts sided with the liberal wing in June Medical Services v. Russo to strike down a Louisiana law that would have restricted abortion access. On Wednesday, Vice President Mike Pence lashed out at Roberts in an interview with the Christian Broadcasting Network, calling him “a disappointment to conservatives.”

Some anti-abortion-rights activists may dream of building a postabortion future. But for the present, the political fight is all-consuming. “One thing is clear,” Pence tweeted in June: “We need more Conservative justices on the U.S. Supreme Court. #FourMoreYears.”