Blog Post

Why are so many of the ‘Great Books’ of the 20th century by people who killed themselves?

By Jonathon Van Maren

This column was first published on April 21, 2017.

Recently, I’ve been reviewing Rod Dreher’s new book The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation, and one of the forms of homeschooling education he is quite effusive about is the “Great Books” program, which leads students through the seminal works of Western Civilization—or what was once know as “Christendom.” The “Great Books” curriculum reads like a list of works blacklisted by campus social justice warriors for white privilege, heteronormativity, and minefields of microaggressions: Aquinas, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Goethe—it’s a library triggering enough to cause a Berkley riot.

And yet, at one point, these were authors any educated person was simply expected to be familiar with.

The decline in literary knowledge and the rejection of those who created the society and liberties we now enjoy is a crisis that has already been detailed extensively. Alan Bloom’s 1987 classic The Closing of the American Mind, and Mark Bauerlein’s 2009 update for the following generation The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future are two must-reads on the subject. But what I find particularly interesting is that slowly but surely, a new canon of post-modern classics is moving in to take the place of the great classics, books that explore the nihilism and hedonism of the years before and after the cultural revolutions that shook Western Civilization to its core. Many of these books were once revolutionary, but are now historical in that they explain the shifts in consciousness that we still live with today.

The other day, for example, I was leaving a large bookstore and my wife handed me a list titled “50 Books You Must Have Read To Be Well-Read.” I usually see these shorts of lists as a bit of a challenge, and I began to scan through their selection. I’d read many of them, but what struck me was the sorts of books they’d chosen.

There was Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, a semi-autobiographical account of young Esther Greenwood’s descent into depression, crushing in its disturbing monotony and culminating in Greenwood’s suicide attempt, subsequent electro-shock therapy, and acquisition of a diaphragm which then gives her the “freedom” to pursue sexual relationships without the fear of pregnancy or pressures to get married. Sylvia Plath was successful in her own suicide attempt a mere month after The Bell Jar was published in the United Kingdom.

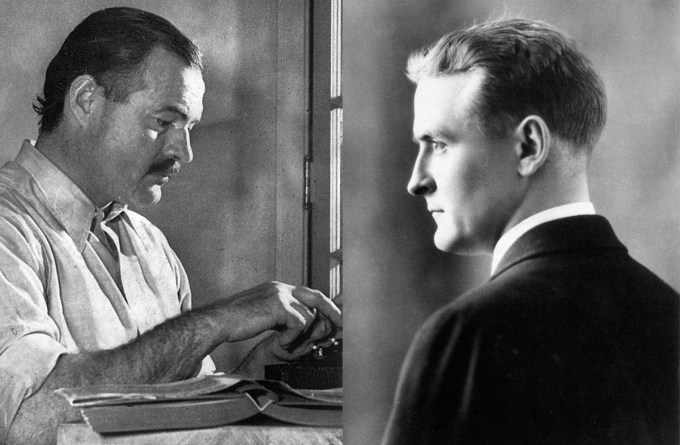

Then there was the beautifully written but teeth-grindingly cynical The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Much of Fitzgerald’s work featured the alcohol-fueled, party lifestyle he himself lived and that contributed to his early demise in 1940 at the age of 44. The cynic and nihilist Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five was also quite high up the list, a novel of flashbacks which includes some of his own experiences in the wake of the World War II firebombing of Dresden. One of Vonnegut’s driving points was a simple one: if the Christian God is involved, He must be evil.

For some reason, Allen Ginsberg’s weird, homoerotic, semi-literate poem Howl was also included. Howl, serving as Ginsberg’s condemnation of a generation that condemned the sorts of drug-fuelled sexual liaisons he defiantly celebrates in this freewheeling free verse rant, is now apparently considered a great work of American literature. Ginsberg, also known for poetic works like “My Sphincter,” is worshipped in academic circles—one of my English professors once began a semester by marching into the classroom reciting Howl at the top of his voice.

Ginsberg was a close associate of another writer on the list, Jack Kerouac. Kerouac and Ginsberg were part of an artistic movement now referred to as the “Beat Generation,” which paved the way for the more overt social rebellion of the ‘60s and ‘70s. It is Kerouac’s On the Road that we are told qualifies as a classic here—the Modern Library even ranked it as number 55 on its list of the 100 top English novels of the 20th century.

Kerouac, a literary iconoclast, delivered in novel form what Ginsberg had in Howl: an alcohol-sodden and drug-laced trip, but this time a literal road trip across America. Kerouac successfully drank himself to death by the age of 47. Ernest Hemingway, another brilliant writer who made the list, was an alcoholic who shot himself in the head at age 61. Hunter S. Thompson, whose apparent genius I cannot discern no matter how many times I pick up his work, killed himself in a similar fashion at age 67.

It’s not that these men and women are not incredibly talented writers. Fitzgerald’s writing is at times breathtaking. Plath’s work can cut to the bone. It’s the fact that it is now these works that make up the new canon of Western literature, work that is considered to be representative of our society.

Sadly, that is true. Only one of Shakespeare’s plays made the list. The King James Bible, which with Shakespeare defined the English language as we know it, doesn’t make the cut. Aside from Dante’s Divine Comedy, neither does any other religious work. The values and beliefs that created Western Civilization and defined it for centuries are for the most part absent, replaced instead by men and women who dedicated their talents to haunting, post-modern horror stories of meaninglessness and hedonism.

Our society has nearly flipped in its approach to great literature. Poems like Howl, which celebrate anonymous sodomy and constant intoxication, are now part of the canon. The Bible and so many works of literature that towered in the cultural imagination for centuries are now considered to be hate speech written by hateful white men. Perhaps the chaos that grips university campuses across the country can be better understood when we realize the sorts of prophets the professors have chosen—and which ones they have rejected.