Blog Post

Son of Solzhenitsyn

By Jonathon Van Maren

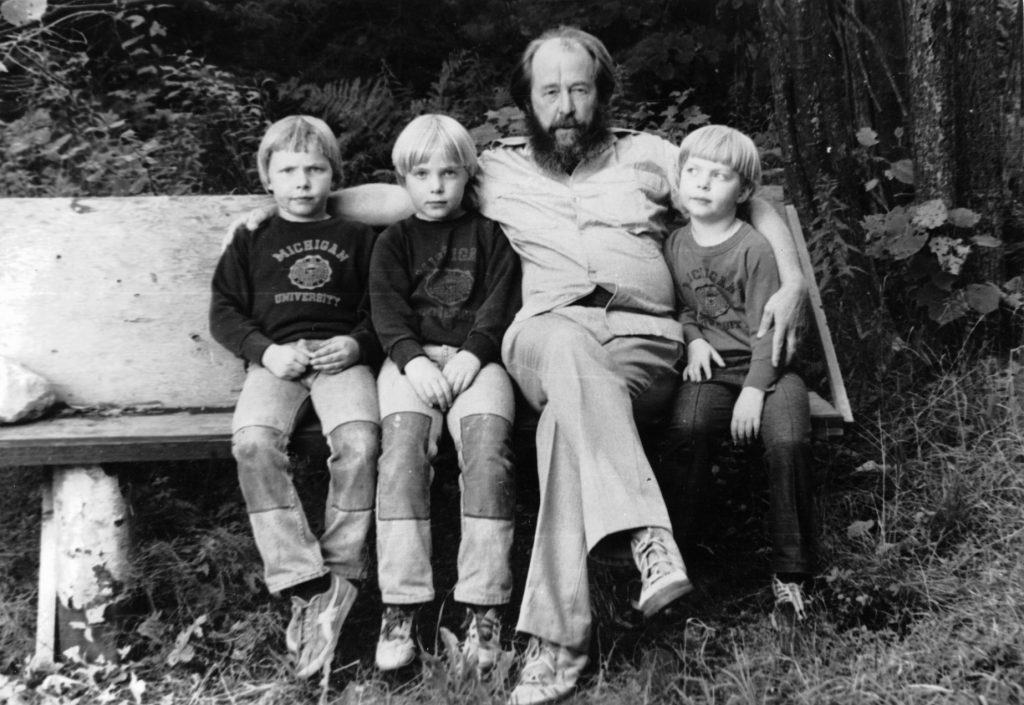

When Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn left the Soviet Union in February 1974 as one of the most famous exiles of the twentieth century, his son Ignat was not yet two years old. The author of The Gulag Archipelago, long a thorn in the side of the Soviet regime, was charged with treason and forcibly evicted from his homeland. The family ended up spending two and a half years in Zurich, and then moving to America, where they spent eighteen years in exile in a small town in Vermont. Only in the 1990s could the Solzhenitsyns at last return to Russia.

Ignat Solzhenitsyn is now 48 years old and a world-renowned Russian-American conductor and pianist, the principal guest conductor of the Moscow Symphony Orchestra and the conductor laureate of the Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia. Born in Moscow under communism, exiled to America with his parents and two brothers, and able to return after the long Soviet nightmare finally came to an end, Solzhenitsyn, who currently resides in New York City, has a singular understanding of what home means.

The exile was often discussed in the Solzhenitsyn home. “One of my earliest memories is my father explaining that Russia was under an evil spell, as so often happens in Russian fairy tales, and so we were waiting for the day when the spell was broken and we would be able to go back,” Ignat told me. “Little by little, we understood as we got older and were able to read for ourselves what it was all about and why we found ourselves in the USA—and the magnitude of our father’s work.”

Ignat had no concrete memories of Russia as he grew up—“just a couple of almost photographic memories in my mind, no memory of experiences”—but his parents taught him and his brothers what it meant to be Russian. Ignat’s mother Natalia Svetlova—who served as Aleksandr’s “editor, publisher, type-setter, and critic all rolled into one”—educated the boys in Russian literature, poetry, and the language.

“We needed extra emphasis in that area because we were cut off from the mother tongue,” Ignat said. The boys were raised Russian Orthodox, which also placed them within a tightly-knit community “that doesn’t have much to do with the outside world.” It was an island of Russianness in the midst of a distinctly non-Orthodox nation.

Aleksandr, while often preoccupied with writing, made his time with his sons “really count.” He taught them literature, astronomy, Russian history, philosophy, and geometry. After listening to the BBC and the Voice of America on a shortwave radio, he would tell his family about current events, which they would often discuss at the dinner table. This, of course, continued during the time of Aleksandr’s exile within his exile—when his Warning to the West speeches critiquing Western culture deeply offended many of his hosts, both liberal and conservative.

The news of the day, of course, often highlighted the ongoing clash between the Solzhenitsyns’ homeland and the land of their exile. “Not everyone was able or willing to distinguish between Russian and Soviet, despite the fact that my father memorably noted that Russian is to Soviet what man is to disease,” Ignat told me. “There were some difficulties in school. Young kids, our peers, could not readily make that distinction. When Soviet tanks rolled into Afghanistan in ’79, for example, or when martial law was declared in Poland in 1981. Those harsh Cold War realities definitely intruded and affected how our peers saw us.”

“They might call us Soviet spies,” he recalled. “‘What are you guys doing here? Go home!’ But overall, we met with the typical generous American welcome and understanding and open arms, things I think have never changed in the United States.”

The world media covered Aleksandr’s return to Russia in 1994 extensively, including Aleksandr’s speech to the crowd assembled to greet him at the train station in Moscow. His son’s homecoming a year earlier, in 1993, was also an emotional experience. “I came back first on tour,” he said. “I was piano soloist for the National Symphony Orchestra from Washington. I went on tour to Moscow, St. Petersburg, and the Baltic countries. I came first and foremost as a pianist, but also as the son of my father and a son of Russia returning after almost exactly two decades away.”

“Those were amazing days—to be subsumed in a sea of Russianness all around me,” he said. “Not just certain people or just a group of people but everything, everybody, the whole mass of people, to hear hundreds of people talking all at once on a metro train and to see the Russian signs—just prosaic, nothing special, just ‘milk’ or ‘groceries’ and directions—seeing and hearing and smelling Russian was just incredible.”

Ignat said that there is something mysterious and indescribable to him about home. “We were reared in that natural love for our homeland, for our culture, and her language and her people, her composers and her artists,” he told me. “To go back home really was going home, even though for us children, we also had the home where we grew up and the country to which we were grateful and of which we also felt a strong part, so there is a duality there. These questions to do with home and belonging are fascinating and difficult ones to identify and verbalize, because they seem to go right to our subconscious; to some innermost area that is not open for easy examination.”

Ignat experiences this sense of two homes as “going back and forth, literally, physically, and culturally.” The prescient warnings of his father to both West and East still beckon us to introspection. “Ultimately, the big questions are: Why are we put on earth? What is the purpose of our existence, assuming it is more than just filling ourselves with material things . . . It is in that area that West and East certainly come together, and it is in that area that Solzhenitsyn’s warnings are most relevant today—because we must always, first and foremost, care for our soul and the souls of our neighbors.”

Because as all true home-seekers have understood, we are to be pilgrims here below—striving for a different home far beyond physical borders in the City of God.

First published at First Things.