Blog Post

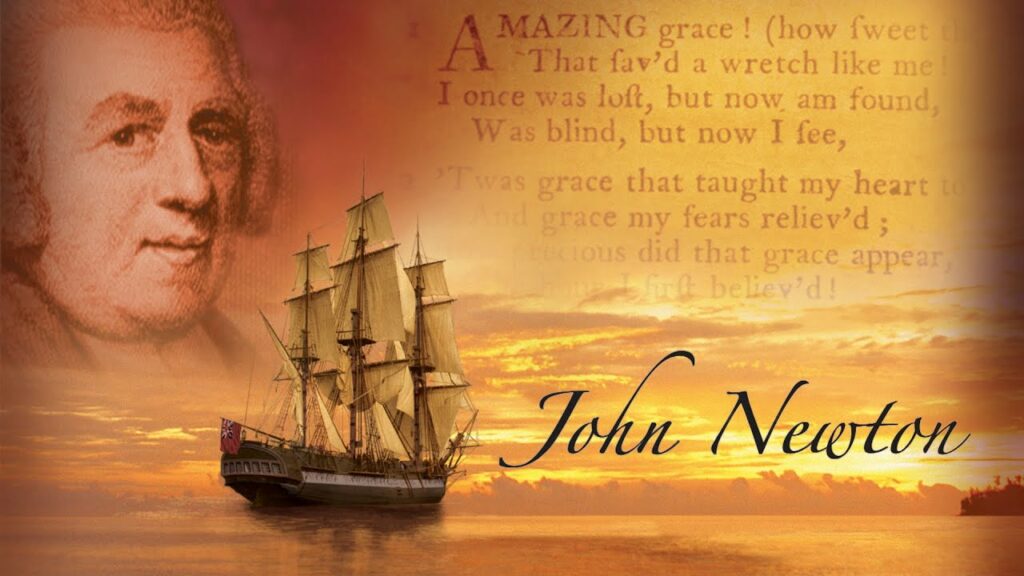

John Newton, William Wilberforce, and Handel’s Messiah

By Jonathon Van Maren

Each Advent, I try to attend a performance of George Frideric Handel’s Messiah, one of the most beautiful compositions of Christian music created in the last several centuries. Taken verbatim from the King James Version of the Bible and the Psalter of the Book of Common Prayer, Handel’s oratorio begins with the prophecies of Isaiah and others; explores the annunciation to the shepherds; lingers on the Passion, and ends with the resurrection of the dead and Christ’s triumph in heaven. His Hallelujah chorus famously drew King George II to his feet during the 1743 London premiere — all audiences since have likewise stood.

The story of how Handel’s Messiah came about is itself an extraordinary one. Scarcely sleeping and eating, Handel composed the oratorio in a mere 24 days. At one point, his servant came upon Handel while he was working on the Hallelujah chorus and found his face drenched with tears. “I did think I did see all Heaven before me, and the great God himself seated on His throne, with His company of angels,” he exclaimed. Late another evening, he was found with tears streaming down his face, blurring the ink on the page before him. The servant was able to make out the words: “He was despised and rejected of men, a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.”

The now-ubiquitous Christmas oratorio was not, at first, received kindly by the critics — although the 1742 premiere in Dublin sold out and the author Jonathan Swift, dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, permitted his choir to participate. It would be some years before Messiah was recognized as the work of majesty and genius that it is today, and even secular music critics now flock to hear it each holiday season.

I have long been fascinated by the abolitionist movement that began in Great Britain shortly after this period and recently discovered a connection between the great oratorio and the social reform movement begun by William Wilberforce. In 1784, an Anglican minister named John Newton — a former slave trader and sailor — grew concerned that the enormous crowds packing Westminster Abbey to listen to Handel’s now wildly popular Messiah on the centenary of his birth were missing the real significance of what he called “the several sublime and interesting passages of Scripture, which are the basis of that admired composition.”

READ THE REST OF THIS COLUMN HERE