Blog Post

Live Not By Lies and Estonia’s Singing Revolution

One of the most powerful documentaries I have ever watched is The Singing Revolution, a 2006 film that chronicles the extraordinary struggle of the small Baltic nation of Estonia against Soviet occupation. From 1987 to 1991, thousands of Estonians expressed their defiance by gathering to sing the songs of their people, galvanizing resistance movements and leading to the restoration of Estonian independence. “Until now, revolutions have been filled with destruction, burning, killing, and hate,” Estonian journalist Heinz Valk famously proclaimed, “but we started our revolution with a smile and a song.”

Since 1869, people had traveled from all over Estonia every five years to attend a music festival called “Laulupidu,” uniting the nation in the face of occupiers for over a century. Up to 30,000 singers would take to the stage at once. Estonia has one of the largest collections of folk songs in the world, and the Soviets recognized this inheritance as an arsenal. The festival became the source of a power struggle. The Soviets demanded propagandistic songs praising Communism; Estonians resisted by concluding with their own. These musical acts of defiance kept hope alive during fifty brutal years of oppression.

When Gorbachev announced Glasnost, cautious protests began. First, in 1987, against a Soviet strip-mining plan. The Heritage Society was founded, and dissidents began to openly talk about the history of the occupation. Thousands showed up at a demonstration; it was the first time in fifty years anyone had spoken up and got away with it. In April 1988, 10,000 came to a protest. A summer music festival featured Estonian songs at festival grounds where, for several consecutive nights, tens of thousands arrived to sing—and wave the national flag. The demonstrations grew.

On September 11th, 1988, an estimated 300,000 people—roughly 20% of the population—poured into Estonia’s Tallinn Song Festival Grounds. It was one of the largest mass gatherings in the country’s history. Key figures in the independence movement gave rousing speeches; Heinz Valk, who coined the phrase “Singing Revolution,” made his famous declaration: “One day, no matter what, we will win!” People wore folk costumes sewn by their grandmothers; thousands waved flags. They sang banned anthems, traditional songs, and the independence movement’s “Five Patriotic Songs” series. Many feared a Soviet crackdown and a bloodbath. It did not come. Instead, it set off a chain of political events that would culminate in Estonia’s freedom.

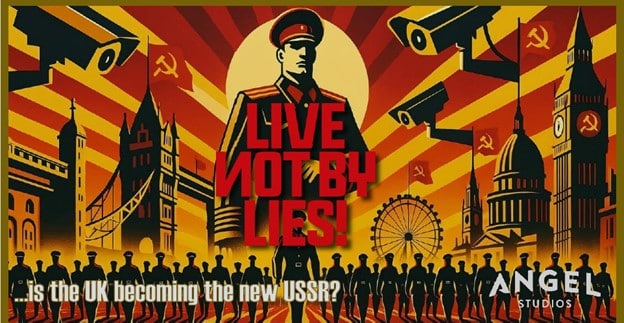

Three decades after the collapse of the Evil Empire, writer Rod Dreher traveled to nations of the former Soviet bloc to interview dissidents and study their tactics of resistance. According to Dreher, the West—the victors of the Cold War—is now post-Christian, and slouching slowly but inexorably towards the type of totalitarianism once endured by those who lived behind the Iron Curtain. The result was the runaway 2020 bestseller Live Not By Lies, which has just been released as a four-episode documentary series by Angel Studios.

The series opens with examples of the crackdown on social conservatives unfolding across Western Europe, including UK pro-lifers being arrested for silent prayer. One particularly sinister scene shows a police officer asking, with a distinctly menacing undertone: “Are you here to pray for the lives of unborn children?” Dreher explains the origin story of the book and documentary: people who had lived behind the Iron Curtain telling him, time and again, that what is happening in the West gave them a keen and disturbing sense of déjà vu.

The series weaves a potent analysis of totalitarianism with stories of heroes who lived lives of quiet defiance behind the Iron Curtain, maintaining their faith, their dignity, and their morality while the torture chambers of the state yawned at them. Kamila Bendová, the Catholic den mother of Czechoslovakia’s dissident group Charter 77, who was left with five children when her husband Václav, the spokesman, was imprisoned. Richard Wurmbrand, the Evangelical Lutheran pastor who endured fourteen years of torture in Nicolae Ceaușescu’s Romanian prisons. The stories of breathtaking courage alone make the documentary worth watching.

In the West, Dreher notes, comfort is the new gulag. The hellholes of Communism have given way to chosen chains: pornography, perpetual entertainment, ubiquitous digital addiction. This functions like the drug “soma” described by Aldous Huxley in his dystopian novel Brave New World, which provides surges of happiness and thus suppresses dissent. Dreher is right. If anything, the point is understated. In a decade of working with porn addicts, I can say that while the chains might be chosen at first, they are cripplingly difficult to shed.

READ THE REST OF THIS COLUMN AT THE EUROPEAN CONSERVATIVE