Blog Post

The Mutual Hatred of William F. Buckley and Gore Vidal

By Jonathon Van Maren

The bare-knuckle brawling of public intellectuals has always been a common phenomenon. Usually, those intellectuals have had a healthy respect for one another, if not admiration. The playwright George Bernard Shaw was one of the first to write a letter of condolences and offer help to G.K. Chesterton’s widow. The left-wing atheist Christopher Hitchens, who went up against William F. Buckley’s conservatism on Firing Line many times, was observed bellowing John Bunyan’s “He Who Would Valiant Be” in the pew of St. Patrick’s Cathedral at Buckley’s funeral. But there was one public intellectual whom William F. Buckley despised, and was despised by in return: Gore Vidal.

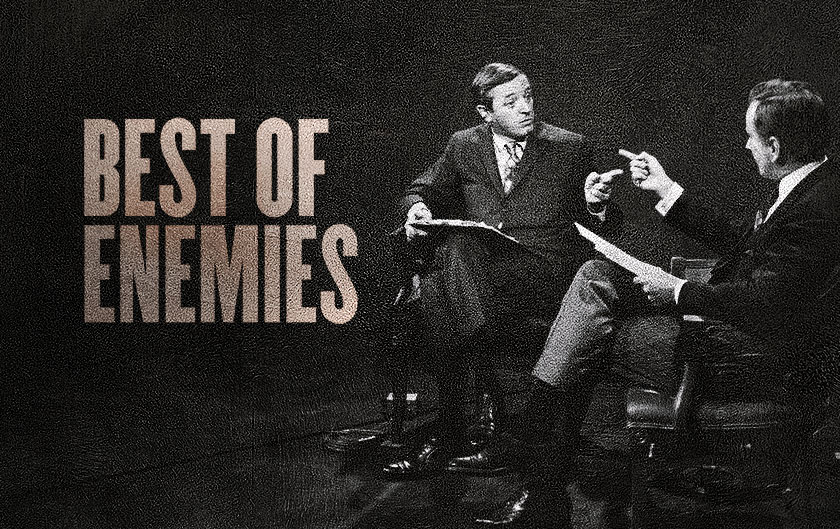

This relationship of mutual ill-will is the topic of a new documentary just completing the film festival circuit and hitting theatres, Best of Enemies. It is based on the famous 1968 debates between Buckley and Vidal at the Republican and Democratic conventions, featuring the famous exchange in which Vidal baited Buckley by calling him a “crypto-Nazi.” Straining from his seat in fury, Buckley famously snarled, “Now listen, you queer, stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I’ll sock you in your expletive face, and you’ll stay plastered.”

The documentary makes much of this moment, but does not include a fascinating insight related years later by WFB’s son, Christopher, upon the occasion of Gore Vidal’s death: “If you look closely at the footage of the 1968 TV contretemps between WFB and Vidal, you’ll see him physically straining, but something holding him back. A few days before, [WFB] was sailing in Long Island Sound when a Coast Guard cutter zoomed past his sailboat, knocking him to the deck, breaking his collarbone. During the Chicago debates, he was wearing a clavicle brace. It’s possible that the brace prevented the moment from being truly iconic.”

Best of Enemies (I was kindly provided a reviewer’s copy by Video Services Corp), makes the case that this moment was iconic. The 1968 Buckley-Vidal debates, it posits, were the beginning of modern television and the age of pundit news, the era of Sean Hannity and Bill O’Reilly, Chris Matthews and Rachel Maddow. In this sense, the documentary makes one somewhat nostalgic—today’s pundits are a faint shadow of the intellectual titans clashing with magnificent eloquence and exhilarating turns of phrase.

William F. Buckley, of course , was that era’s top conservative intellectual. From writing his widely-panned God and Man at Yale to founding his magazine National Review, Buckley was already a prominent player on the political scene. He had backed Barry Goldwater’s failed nomination in 1964, and was just beginning to assist the rise of Ronald Reagan, a fact Vidal alluded to many times throughout the 1968 debates, sneering at Reagan as an “aging juvenile Hollywood actor.” Strange words coming from a playwright, Buckley responded wryly, and Vidal’s face twisted as Buckley noted that perhaps this bitterness emanated from Vidal’s only sporadic success in Hollywood. As one writer noted, Buckley, with his charm and intellect, “could have been the playboy of the Western world—but instead chose to be the St. Paul of the conservative movement.”

, was that era’s top conservative intellectual. From writing his widely-panned God and Man at Yale to founding his magazine National Review, Buckley was already a prominent player on the political scene. He had backed Barry Goldwater’s failed nomination in 1964, and was just beginning to assist the rise of Ronald Reagan, a fact Vidal alluded to many times throughout the 1968 debates, sneering at Reagan as an “aging juvenile Hollywood actor.” Strange words coming from a playwright, Buckley responded wryly, and Vidal’s face twisted as Buckley noted that perhaps this bitterness emanated from Vidal’s only sporadic success in Hollywood. As one writer noted, Buckley, with his charm and intellect, “could have been the playboy of the Western world—but instead chose to be the St. Paul of the conservative movement.”

Gore Vidal, on the other hand, was America’s predominant libertine writer, unabashedly advocating for a world of uninhibited sexual freedom and socialist politics. Politics, Best of Enemies notes, was always Vidal’s first love—he was actually related to Jacqueline Kennedy and ran for Congress as a Democrat. But it was his social commentary and his novels—I may be repeating myself—that led to his great success. In particular, his hedonistic anthem Myra Breckinridge, about a flamboyant “transsexual” who undergoes a sex change, was seen by William F. Buckley and many others as vile pornography. The documentary unfortunately includes two short but lewd scenes from the resulting film—one which, incidentally, Vidal himself repudiated as an awful piece of work.

It was these two visions of America clashing onstage in that most pivotal of years, 1968, that led millions of viewers to tune in to the then low-rated ABC News. It was this event, Best of Enemies says, that changed television forever. In those days, after all, over 80% of Americans actually watched the respective party conventions—and Buckley and Vidal didn’t disappoint. Their desire to verbally discredit and destroy one another on national television made for a fascinating debate—and debate as blood sport, at that. This against the backdrop of Mayor Richard Daly’s Chicago, with police brutality and tear gas wafting through the streets.

This is where Best of Enemies falls into the very trap it seeks to highlight: Sensationalism. Eric Alterman, media historian, is quoted noting that Buckley “did what pundit television should do—he elevated the discourse and he educated people by it.” Unfortunately, the filmmakers focus so much on the barrage of witty insults flying back and forth that they take virtually no time to examine the arguments being put forward by Vidal and Buckley, other than those that shed some light on personal characteristics of the commentators. There are many fascinating themes to pursue here—the decline of intellectual discourse in the media, the polar opposite cultural ideologies of Buckley and Vidal, or even the political impact of public intellectuals in a time when everything seemed in flux. But Best of Enemies chooses to only touch briefly on these themes, focusing mainly on the mutual hatred of these two powerful patrician personalities.

There is a second bias here, too—not overt, but still perceptible. It is stated as fact that Buckley’s success was that he created the coalition of angry white voters, a lazy and tired trope at best. References are made, too, to the aspersions cast by Vidal and others on Buckley’s sexuality—admittedly unfounded, but still noted. To be fair, then, the filmmakers might have made note of a much more serious accusation made against Vidal by a number of relatives after his death—that he was a pedophile. This is not particularly unbelievable, considering that Vidal refused to call himself gay, preferring the term “pansexual,” and had even stated in print that he was attracted to adolescent boys. Some speculate that Buckley may have had evidence of this on file, as he was in possession of an enormous filing cabinet labeled “Vidal Legal,” bulging with papers on his archenemy. WFB’s son Christopher heaved these files into the dumpster upon his death. To Vidal’s accusation, even in the event of Buckley’s death, that WFB was a “hysterical old queen,” Christopher responded with a dismissive, “Whatever.”

That said, Best of Enemies is still a fascinating watch. Reid Buckley, the late Christopher Hitchens, and numerous other Buckley and Vidal associates give fascinating insights into the times and personalities. The acerbic back-and-forth of verbal combat is fantastic entertainment. And beyond a few regrettable curse words uttered in the heat of the moment, the debates make for delicious viewing.

Vidal and Buckley are, of course, both gone, although the debates they fought still rage on. It’s interesting to note that while Buckley went on to become a political king-maker and highly influential political figure, while Vidal later in life faded increasingly from public view, it is the world Vidal advocated for that has, for the moment, won the culture war. Myra Breckinridge and similarly pornographic offerings from Vidal are almost passe in a culture drenched in pornography, and Vidal’s work has long lost its ability to outrage or shock. On the other hand, the traditionalist views of William F. Buckley are no longer mainstream, and much of his cultural commentary would today unleash the hellhounds of social media and the digital lynch mobs of our politically correct society. That, I think, is what Best of Enemies highlights best—an era where philosophies could still be debated bluntly, openly, and with a brilliance that is as foreign as the patrician drawls of the icons emitting them.