By Jonathon Van Maren

One of the more common questions I get after giving presentations on pornography is how I manage to unwind after spending an hour or so explaining how pervasive and pernicious porn is, and then fielding questions and having conversations filled with horror stories of the swathe of destruction porn has cut through people’s lives. It’s a good question—as my colleague at Strength to Fight Josh Gilman always says, porn is poisonous—even spending too much time researching it or talking about it has an impact on you. It took me awhile to figure out how to distract myself from the material I’d just covered.

One of the things I had to do was rediscover literature that highlights what I call “the high drama of ordinary living.” I’ve always loved literature, but in the last six years or so I’ve spent most of my time reading nonfiction as a result of researching for my own book, writing several weekly columns, and simply trying to keep up with the newest cultural research. But after doing a presentation on how porn culture metastasizes into rape culture, I need to read something that highlights the best in life: family, friends, hard work, and simpler times.

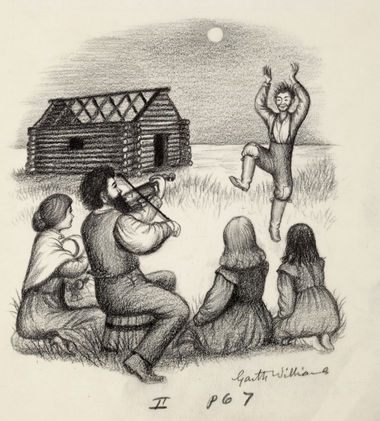

This weekend after a homeschooling conference where I spoke to dozens of parents, for example, I pulled out of the parking lot and popped in the audiobook version of Little House on the Prairie by Laura Ingalls Wilder, the story of the Ingalls family’s journey from the woods of Wisconsin to Indian Territory a few miles away from Independence, Kansas. The Little House books were written for children, but my father and my grandparents reread them many times throughout adulthood, and remembering the descriptions of day-to-day life for a frontier family and all the little joys and sorrows that went with it, I decided to revisit them myself.

As I drove, Pa’s fiddle sang the fire flames high into the prairie sky and the embers turned to cold white stars, the prairies teemed with dipping and soaring birds that made the grasses throb with song, Pa’s mustang bolted across the plains after happening upon a pack of fifty huge wolves, and he was greeted back in the cabin by a family that always awaited his return with bated breath. Wilder describes a world that is long past, but she describes people that we can all relate to. They feel the things we feel, and the Ingalls family soon becomes as real as a family we know personally.

It is because of that connection, built by the power of the written word, that so many people flock each year to De Smet, South Dakota, where the last house Charles Ingalls built with his own hands in 1887 still stands, filled with personal belongings of the family that you can recognize from the books. As my brother and I were driving to visit Mount Rushmore a few years back, we heard from a local that Carrie Ingalls had lived in Keystone after marrying a widower who’d had a role in naming it, and we swung up a mountain road to see the church she’d attended. Her stepson Harold, apparently, had been one of those who worked on sculpting the famous Mt. Rushmore presidential heads.

But it is because the family is so alive in the books that a visit to the De Smet graveyard is a strange experience. I arrived there with my brother at dusk a few years ago and saw the gravestones of Charles and Caroline—Ma and Pa, Laura’s sisters Mary, Carrie, and Grace Ingalls, and the little son Laura and Almanzo lost as an infant (as she recorded in The First Four Years.) It was quiet in the cemetery, without so much as a bird singing. The heavy silence and the aging gravestones were such a contrast to the images that filled our mind from Laura’s storytelling that we didn’t stay long.

But revisiting these books again a few years after my visit to De Smet and quite a few years since I read them last has brought the Ingalls family to life again for me. Wilder’s writing is superb and her stories hold my attention just as they did when I was first reading them. It is her descriptions of a loving family life, with sisters who love their parents and each other, who sacrifice for each other, and who do everything with someone else in mind first, that really provides a contrast and distracts me from the ugly modern topics I present to audiences at conferences nearly every week. Wilder’s writing reminds me, at the end of the day, what we’re fighting for in the first place: loving families, unpoisoned by the toxic material our modern culture is now awash with. Wilder reminds us what families were, and what families can be—and that’s precisely the distraction and the encouragement I need sometimes.

I appreciate your columns and commentary. You have a unique voice. As you continue to speak out and need continued literary refreshment, I recommend you take a look at the Little Britches series by Ralph Moody, a series I have read a couple of times. I describe them as a more masculine version of the Little House books. They are set around 1910 to early 1920s, mostly in the American West, but some are in New England as Ralph depicts his coming of age years. The quality of the writing is perhaps a tad lower than Laura’s, but the adventures are a notch above hers. Both series are rich in character as families and individuals face and overcome adversity.