By Jonathon Van Maren

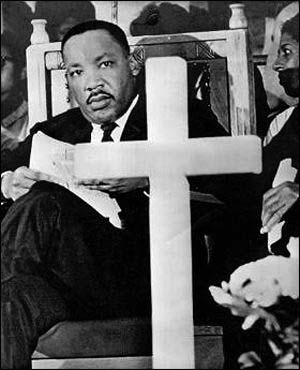

Every year, organizations and activists of every stripe greet Martin Luther King Jr. Day by expressing why his work inspires them and how King’s legacy is being carried on. Increasingly, King is made out to be a secular hero who championed “progressive” causes, and social media is flooded with assertions that the militantly anti-Christian Black Lives Matter is the new Civil Rights Movement, carrying on the work of Rev. King. But what Martin Luther King Jr. Day really drives home is the extent to which there is no longer a unified national consensus on where we derive our rights and where morality comes from.

Revisiting the history of the Civil Rights Movement is essential to understanding race relations today. Too many people are willing to write off the concerns of black communities as groundless, asserting that the injustices perpetrated against African Americans are entirely historical, that the page has been turned, and thus we can all move on. But it is important to remember that there are those who still carry with them the memories and the scars of segregation, and that for many people, these injustices are not yet history—they are still lived experience. Late last year I interviewed 95-year-old George Walker, the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music. Walker actually recalls hearing from his grandmother, who had been a slave on a Southern plantation, what that awful time was like. “They did everything but eat us,” she told her grandson. The fact that I could speak to an old man who could remember hearing with his own ears about the experiences of slavery from a woman who endured it gives you a little idea of how fresh some of these experiences still are.

It is also important to revisit this history in order to realize something that is being intentionally ignored by many: The Civil Rights Movement was, especially at first, a primarily Christian movement that was appealing to the American people based on shared Christian values and explaining to them from Scripture why segregation and racial injustice were not only incompatible with the principles of democracy, but were sin in the eyes of God. King scarcely gave a single speech without quoting hymns and Bible texts, and his 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” is perhaps one of the most thoroughly religious documents in recent American history. “A just law is a man made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God,” he wrote. “An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law…Paul Tillich has said that sin is separation. Is not segregation an existential expression of man’s tragic separation, his awful estrangement, his terrible sinfulness?”

Such language is so foreign that many prefer to forget the fact that King was a Baptist pastor—as were most of the Civil Rights leaders. Several years ago, I interviewed James Zwerg, a Civil Rights activist who was famously beaten nearly to death on the 1961 Freedom Rides in Montgomery, Alabama. He joined the movement after his black friends showed him, from Scripture, that segregation and racial injustice were evil. “It finally hit me one day that for me, as a Christian, the story of the Gospels was the most powerful story of nonviolent direct action ever written, that Jesus embodied all those principles of nonviolence, the love for your enemy, the forgiveness, the innocent suffering, the attempt to educate,” he told me. “I mean, it was all there. And it just hit me, and I decided at that moment to embrace nonviolence, to actively take part [in the Civil Rights Movement.]”

Zwerg was willing to act on his convictions regardless of the cost—at the very first demonstration he took part in, he was knocked out by a man wielding a monkey wrench and dumped into the street. It was the Christian principles that underpinned what they were doing and the prayer they relied on that gave them the courage they needed, Zwerg told me. When I asked him about the increasingly secular portrayals of the Civil Rights Movement, he was emphatic about the fact that the Civil Rights Movement operated from a fundamentally Christian basis: “Where did we meet? In churches. Who were our advisors? Ordained clergymen.”

Christianity not only formed the basis of the principles that Civil Rights leaders were advocating, it informed the lives of the men, women and children on the front lines. Ruby Bridges, the six-year-old girl who braved a gauntlet of screaming white men and women each day to attend school in an empty classroom—the first black child to attend a newly integrated school, saw horrific things—including a white woman that greeted her on the way to school with a coffin with a little black doll inside. Bridges coped, she told me in an interview, by praying for those who directed this vitriol at her: “I believed I should pray for them…I would say my prayers before school and after school, and if I forgot to say them, I would go back and say my prayers.”

Five hundred children had been withdrawn from the school Ruby attended, and one child told her that he couldn’t play with her “because you are a nigger.” Her father, a veteran of the Korean War, was fired from his job. The street her family lived on was blocked off and monitored by federal marshals because of incessant bomb threats. And famously, little Ruby had to be accompanied by armed marshals into school each day for her own safety and protection. And yet, she prayed for her enemies. “I so believed in prayer,” she told me. “I think that was just building my faith. I didn’t realize it then, but now being sixty years old I absolutely stand on my faith and I believe in the power of prayer.”

These stories remind us that the Civil Rights Movement transcended politics. Yes, Martin Luther King Jr. was a deeply flawed man. Yes, the political views of different leaders came from right across the spectrum. But there was still a moral consensus—one based on Judeo-Christian values—that social reformers could appeal to that everyone would recognize and respect. Rev. King did not tell America that their treatment of African Americans was not sufficiently “progressive,” he told them that it was wicked, and he proved it from the Scriptures. To remove Christianity from the Civil Rights Movement is to virtually erase that history entirely.

That is something to remember on Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

__________________________________________________

For anyone interested, my book on The Culture War, which analyzes the journey our culture has taken from the way it was to the way it is and examines the Sexual Revolution, hook-up culture, the rise of the porn plague, abortion, commodity culture, euthanasia, and the gay rights movement, is available for sale here.