Blog Post

Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition: The Anthem of Pearl Harbor

By Jonathon Van Maren

On December 7, 1941, the American naval base at Pearl Harbor was smashed by a stunning attack at dawn. Japanese fighter planes came in waves, with bombs and torpedoes crashing into the ships and exploding into carnage and chaos. It was all over in ninety minutes, and the devastation was immense: 2,335 American servicemen had been killed, and an additional 1,143 were wounded. Eighteen American ships, including five battleships, were either sunk or run aground. A sleeping giant was rudely awakened, and it was a day, as Franklin Delano Roosevelt would so famously say, that would live in infamy.

In the days following the Pearl Harbor attack, a legend began circulating. As the servicemen were pinned down by Japanese planes, the story went, there was an army chaplain who circulated among the beleaguered defenders who were desperately trying to return fire with machine guns and any other weapon they could find. The men, it was said, asked him to say a prayer for them, and in response, the chaplain laid down his Bible, grasped one of the machine guns, and bellowed, “Praise the Lord, and pass the ammunition!” The battle cry breathed courage into the hearts of the sailors, and they began to fight in earnest again.

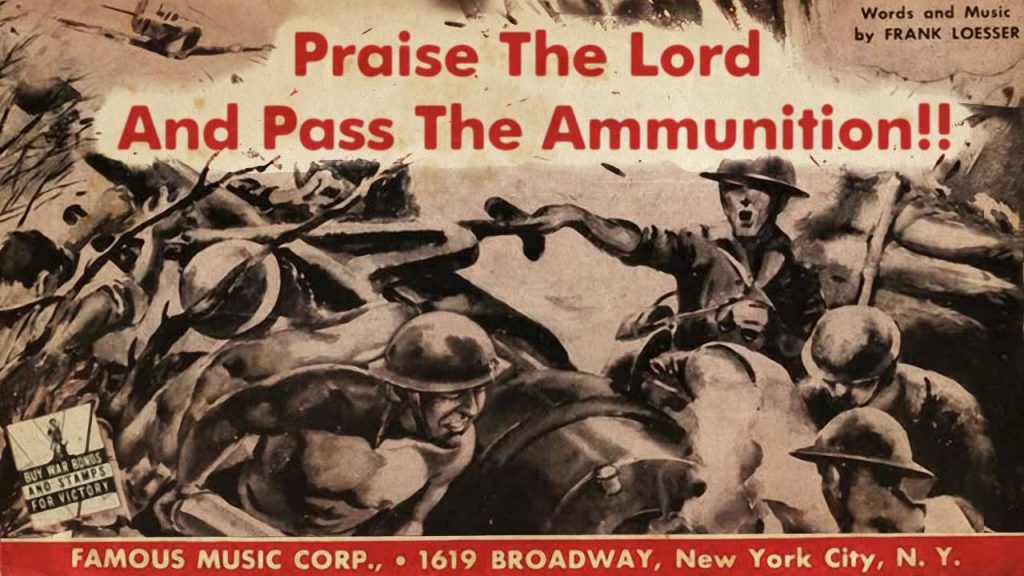

A year later, the American songwriter Frank Loesser got hold of the legend and put the story to song, dubbing the chaplain a “Sky Pilot” and writing in part:

Down went the gunner, a bullet was his fate

Down went the gunner, and then the gunner’s mate

Up jumped the sky pilot, gave the boys a look

And manned the gun himself as he laid aside the Book, shouting

Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition

Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition

Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition

And we’ll all stay free

Praise the Lord and swing into position

Can’t afford to sit around a-wishin’

[or Can’t afford to be a politician]

Praise the Lord, we’re all between perdition

And the deep blue sea

The song, like the Battle Hymn of the Republic before it, soon took on a life of its own, and sold over 450,000 copies in only two months. It became one of those patriotic war songs for both the men and women on the Home Front as well as those in battle, emphasizing the goodness of the Allied cause (and thus, implicitly, affirming the wickedness of the Axis powers.) As legends do, the story soon became accepted as something that had actually taken place during the hour and a half of horror when the Japanese rained hellish fire on the heads of the men at Pearl Harbor.

The truth, as it often does, differed slightly. The chaplain referred to as the “sky pilot” did in fact exist, and his name was Lieutenant Howell Forgy—but he had never actually picked up a machine gun. Forgy was aboard the USS New Orleans when the Japanese attack began. According to the officer in charge of the ammunition line, he heard someone say, “Praise the Lord, and pass the ammunition,” and when he turned, he saw Chaplain Forgy walking along the line of terrified men, patting them on the back, nodding his encouragement. The officer noted that he himself felt tremendously comforted by the words, and turned back to the task at hand with vigor.

After the story turned to legend and was then rendered in song, those who remembered the actual event encouraged Forgy to step forward, but the modest chaplain refused. The legend, he thought, was far more useful as an inspiration for soldiers than what had actually occurred. While the press did manage to identify Forgy as the “sky pilot” and get much of the real story, the chaplain never spoke of it much.

After the war, however, Howard Forgy appeared on the popular game show “I’ve Got A Secret.” While there, he finally recounted his version of what had happened:

Well, I was stationed aboard the USS New Orleans, and we were tied up at 1010 dock in Pearl Harbor when we attacked again. We were having a turbine lifted, and all of our electrical power wasn’t on, and so when we went to lift the ammunition by the hoist, we had to form lines of men—form a bucket brigade—and we began to carry the ammunition up through the quarterdeck into the gurneys, and I stood there and directed some of the boys down the port side and some down the starboard side, and as they were getting a little tired, I just happened to say, “Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition.” That’s all there I to it.

Forgy’s modesty is an example of a characteristic that defined so much of the Greatest Generation. Today, at the memorial for the 77th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, there were no survivors present. Five of them are yet living, but old age has made it nearly impossible for them to travel. This week also saw the funeral of World War II veteran George H.W. Bush, who tried to sign up to fight the day after Pearl Harbor, but was turned away because he was only seventeen years old.

They are almost all gone now. We must honor them and learn from them while we can.

__________________________________________

For anyone interested, my book on The Culture War, which analyzes the journey our culture has taken from the way it was to the way it is and examines the Sexual Revolution, hook-up culture, the rise of the porn plague, abortion, commodity culture, euthanasia, and the gay rights movement, is available for sale here.

My Daddy was stationed at the army base near there. He never talked about it much but once he spoke about driving a jeep toward the naval base and dodging the fusillade. He had turned 30 earlier that year.