Blog Post

Remembering William F. Buckley: A Conversation with Christopher Buckley

By Jonathon Van Maren

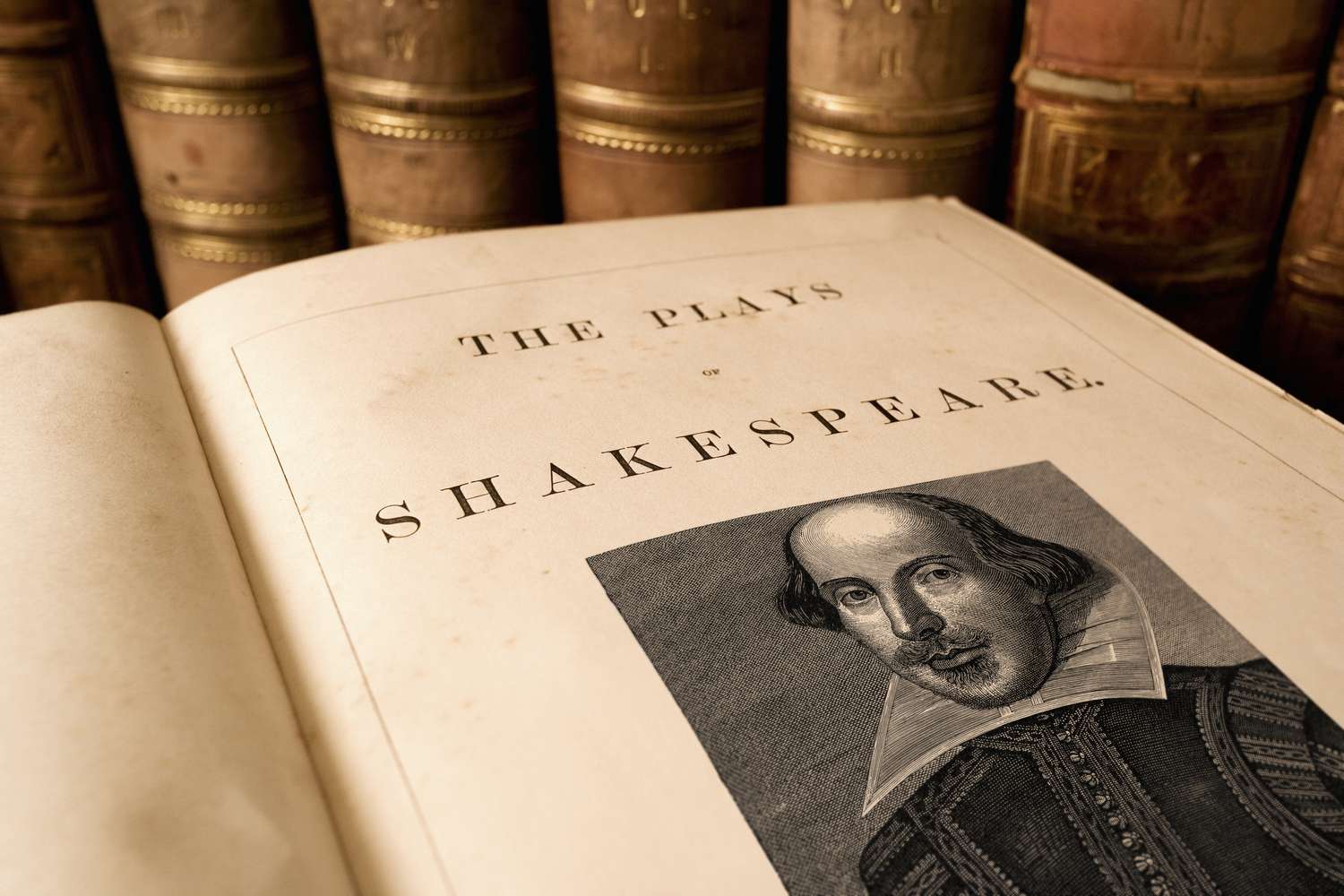

Like any young conservative who wants to become a writer someday, William F. Buckley was one of my heroes back when I attended university in Vancouver (where, incidentally, his wife Patricia hailed from). His resume was so impressive it was hard not to be awed: He founded the National Review, began a conservative revolution, and wrote books and columns on everything from politics to sailing. He hung out and hobnobbed with nearly every prominent figure of his day, from presidents to literary giants, and George Will credited him with ending the Cold War, only somewhat tongue in cheek: Without Bill Buckley, no National Review. Without National Review, no Goldwater nomination. Without the Goldwater nomination, no Reagan presidency, no victory in the Cold War. Thus, Bill Buckley won the Cold War. It was because of Buckley that I always wanted to get published in the National Review (which I did late last year.)

One of the best books I’ve read on William F. Buckley (and there have been quite a few lately: Buckley and Mailer by Kevin Schulz; A Man and His Presidents by Alvin Felzenberg; Right Time, Right Place: Coming of Age with William F. Buckley and the Conservative Movement by Richard Brookhiser) was Christopher Buckley’s powerful memoir Losing Mum and Pup, which he wrote after losing both of his parents within a single year. Christopher Buckley’s specialty is political satire, but his memoir was just beautiful, and I’ve read and reread it several times. It reminded me of the mock episode of Firing Line between WFB and Christopher, which is perhaps one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen.

Last year, on the tenth anniversary of William F. Buckley Jr.’s death, I interviewed Christopher Buckley on his father’s life and legacy. Here is that conversation.

First of all, the big question: Who was William F. Buckley Jr.?

He was a) my father—he was most famous for that, of course. But secondly, I think he is most famous for having founded the modern conservative political movement. He founded National Review magazine in 1955, and you might say the rest is history. That led, one way or another, indirectly to Barry Goldwater, Barry Goldwater led directly and indirectly to Ronald Reagan—who did not, I hope, lead directly or indirectly to our current commander-in-chief.

I read your book Losing Mum and Pup, and I’ve wanted to talk to you since I read that book, because it was honest and touching and heartfelt, but I think one of the things that made it remarkable is that it was not iconoclastic and it is not bitter in the way that so many books written about fathers and mothers are. It didn’t paint over any faults, but at the same time I found it very tender. How did you pull that off?

Well, the honest and modest answer, at least that’s how I hope it sounds, is that I don’t really know. I’ve written 18 books now and each one has been, for me, heavy lifting, pushing the proverbial rock up the hill only to have it roll back down on you. This is the only book among the 18 that I would almost say wrote itself. I had no plans to write the book. My parents both passed away within slightly less than a year of each other. I loved them both deeply, even fiercely, but they were complicated, larger-than-life people. I never planned to write that book until one morning some months after my father died—he was the second one to go—and just started writing it. It took forty days. I oddly sort of checked the calendar and tallied up the days. That was for me a fast book. All of my books have taken much longer than that. It kind of poured out. I took no notes. It was a memoir of my life with these two extraordinary people.

Ten years down the road from the passing of your father and your mother, what memory stands out most vividly to you after the passing of so much time?

That’s a little difficult to say, Jonathon. I think about them, as anyone would with loved, beloved parents, most days. I find myself being asked: What would your father have made of Trump and the modern conservative movement? and I find myself answering, I hope not glibly, that I’m glad he’s not around to see this mess, this chaos. I’m no arbiter, but by dint of being William F. Buckley’s son I’m sometimes asked, “Is Mr. Trump conservative?” And my answer is no, I don’t think he has any coherent political philosophy at all. Someone wrote in the Times that he has no core principles, he has only core whims, and I think that’s a nice way of putting it. I think he is his own ideology. I think it’s all about him. I don’t think he’s ever had a single fleeting thought about anything other than himself. He’s a mega-maniacal narcissist and it scares the pants off me as it does a lot of Americans, although not the 85% of Republicans, my former party, who approve of where things are going. We are in truly uncharted waters.

I used to write political satire, and I’ve written a bunch of political novels, but I’ve given that up. I’ve turned to historical fiction because I just don’t think there’s much point. If I wrote a novel in which I simply recapitulated, word for word, event for event, everything that has happened politically over the last year, year and a half, two years, any half-competent editor or book reviewer would surely say oh, come on. You can’t be serious. So here we are.

It is now impossible to talk about your father without talking about what conservatism has turned into, or at least what the Republican Party has turned into. But I’m not simply talking to a political analyst, but to his son. So I’ll narrow down my question: What do you miss about him the most?

Just about everything. I miss his wit, his sense of fun. He touched the lives of thousands of people almost intimately, and all of them might say that the first thing about him was his sense of fun. He was adventurous—I sailed across three oceans with him. For an intellectual, he really got out of the office a lot. I miss his take on things. I frequently find myself wondering, although I’m glad he’s not around to see this sad carnival we seem to be engaged in, I sorely miss his commentary on it. He was the host of what I think was the longest-running television show with a single host. His show Firing Line ran from 1966 to 1999. He taped something like 1,500 episodes.

What is increasingly remarkable and admirable about it is the high level of the dialogue. He had every leftie and commie that there was on the show, and he accorded all of them respect. He left a number of them bleeding on the mat, but he took apart their arguments, not themselves. Today there’s an awful lot of commentary on TV, some of it pretty good, a lot of it shouting. It reminds you a bit of the mob in Ancient Rome. Increasingly, Firing Line is looked upon rather yearningly as a show that set a certain kind of gold standard. I don’t think we’ve seen its equal yet. That might sound a bit pessimistic. Dear Charlie Rose, who had to set down his microphone when he got swept up in the, well, the unfortunate thing, and I’m not apologizing for him, but he was, to me, the closest thing we had to intelligent, prolonged, rational, analytical, examination of arguments. And now he’s gone, leaving howling whirlwinds in his wake.

As you know, there’s been quite a few books written about your father in the last couple of years, and I’m always reminded when reading about his personal interactions with people of something Martin Amis once said about Christopher Hitchens, that his ideology was friendship first. What happened to the “happy warrior” ethic, the ability to duel ideas without turning the sword on your opponent?

It’s a very good question, and I’m not sure I have any one good answer. I would indict the 24-7 news cycle, social media, the Internet. We move now at a frenzied, almost frantic pace. In the old days—well before your time, young man—there was three channels, one Walter Cronkite, and national newspapers that came out in the mornings. We’re operating at a very hectic pace that I think is often the enemy of reasoned reflection.

Is there anybody who has filled the void he left behind, not on TV but in written commentary? George Will, of course, writes with almost delicious contempt of everything around him, and he wrote a column after the book about your father The Man and his Presidents came out talking about how a new national figure to unite the conservative voting base was needed. Is there anyone, in your mind, who holds a candle to what he did?

Not really. There are some astonishingly gifted right of centre writers, two of them perch on the editorial pages of the New York Times, David Brooks and Bret Stephens, who to my mind is the hottest pen in town. George Will has reached that stage in his amazing career where he deserves to have the word, capitalized, Venerable, put in front of his name like the Venerable Bede. But George is not a spring chicken, he must be in his seventies. So he’s long attained senior statesmanship. The extraordinary thing about my dad, if I may brag—and by bragging I realize how far short of his standard I myself fall—he wrote 57 books, he wrote a thrice-weekly syndicated column, he had Firing Line, he wrote prolifically for every magazine, every publication. He gave up to a hundred or more lectures a year, and he founded a political movement. And he did it, and this is perhaps most poignant and relevant to our own times, by excommunicating the kooks in the right-wing. He excommunicated the John Birchers. He famously said in the National Review that we will not publish, in National Review, anyone who represents or belongs to the John Birch Society because they are simply beyond the pale. He excommunicated the Ayn Randians, and by so doing he created a sort of sensible center where “all the beautiful spirits found themselves,” a vortex of smart and well-intending people. That led, in time, to Ronald Reagan. Those are good innings. My dear old dad, dead ten years ago, has pretty good innings. Plus he married a dazzling Canadian girl from Vancouver, my Mum. Not bad, not bad.

When you describe that kind of output, that time on the road—what was it like to grow up with William F. Buckley as your father?

Well, it was great fun. Sure, he wasn’t around for certain things, but how could he be? You can’t do all that and read Winnie the Pooh to your kid every night. But we were very close. We corresponded—in those days, one wrote letters. My correspondence with my father may run to tens of thousands of pages. The most I can get out of my kids these days, who are about your age, is an eight-character text. We collided, my dad and I. He was an absolute devout Catholic, I am a collapsed Catholic. We butted heads hard on that. We didn’t always agree on political issues, but in the annals of sons, I count myself to be a very, very, very fortunate son. I am eternally grateful to have had the father that I had.

As all these books come out about him, there was a documentary a couple of years back, what do you wish people would remember about William F. Buckley?

There have been various books about various aspects of him. Alvin Felzenberg came out last year, as you mentioned, with William F. Buckley: A Man and his Presidents. The book that I think will be the book is being written by Sam Tanenhaus.

I’ve been waiting for that one for years.

Well, we all have. It’ll be a monster—I say monster in the good sense. It’ll be a big, thick, juicy book. The fact that he’s taken 16 years or more so far—Sam’s been working on other things, to be sure—but he’s going at his own pace. His previous book was a stunning work, a biography of Whitaker Chambers, who my father knew very well. That’ll be a big moment, whenever Sam gets around to publishing it. I tease him lovingly and publicly for taking his time. Good things do take time.

Did you read the book Buckley and Mailer?

I’ve read them all. I’ve enjoyed them all. The one thing I didn’t do was watch the documentary Best of Enemies about his famous clash with Gore Vidal. I made a decision early on to politely decline participating in it, and afterwards not to watch it. It was far from my dad’s most pleasant memory, and I thought perhaps it was a way of honoring his memory. But I note that it was by all accounts very well done.

I was going to ask you that. Your uncle, your friend Christopher Hitchens, and others all participated.

You know, Christopher Hitchens, my beloved Christopher, who left us way too early at the age of 61, when he came to America in the early ‘80s, there was not a lot of daylight between Christopher and Leon Trotsky. Christopher was a Molotov cocktail-throwing leftie. And guess who gave him his start on American TV? William F. Buckley, who admired his mind very much. Here you had two people of absolute opposite political persuasions, and yet they respected and even honored each other. The most mad I think I’ve ever seen my dad was when Christopher decided to go after Mother Teresa and called her…I can’t even remember what he called her…

Thieving Albanian dwarf.

[Laughs] There you go, good for you. I don’t think I saw Pup madder than that, and he wrote a note to his producer scrawled across the offending column I never want to lay eyes on this guy again. But he couldn’t quite see that through. I remember not long afterwards Christopher had written something typically brilliant, it was a takedown of Jacques Chirac on the Wall Street Journal op-ed page, and Pup just said to me with a twinkle in his eye, “Your friend Hitchens sure gave it to Chirac today.” And there was Christopher at Pup’s memorial service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York in May of 2008. He flew in from some speech from Indiana and slipped into the last pew, there was one seat left. And there Christopher, the famous atheist of our time, was heard belting out with everyone else “He Who Would Valiant Be” by John Bunyan. He was very fond of Pup. Perhaps it was a different time. Christopher was very much like Pup in that—well, to requote your earlier comment of Martin Amis, he had friends across the political spectrum, and would that we had more of that today.When you think of William F. Buckley, and you included so many stories in your memoir of him, what story encapsulates who he was?

When I was young, I read Treasure Island, like everyone else. I became fascinated with pirates and buried treasure when I was seven. Pup had a sailboat—we lived on Long Island Sound—and so one day he got a chest and filled it, unbeknownst to my mother, some of her jewelry and Queen Anne silver and buried it across on a little island. And he made a treasure map. I was very excited. We were going to sail across the next Friday. Intervening came the biggest hurricane of that decade, and it completely rearranged the topography of the island and made nonsense of all the clues on the treasure map. Then there came the moment when he had to explain to my mother, who was looking for her earrings and her Queen Anne silver, that he had indeed buried them on an island and that they would likely never be found again. There, I think, you have encapsulated William F. Buckley and Patricia Buckley’s marriage. It wasn’t Ozzy and Harriet, but it sure made for good spectating.

_________________________________________

For anyone interested, my book on The Culture War, which analyzes the journey our culture has taken from the way it was to the way it is and examines the Sexual Revolution, hook-up culture, the rise of the porn plague, abortion, commodity culture, euthanasia, and the gay rights movement, is available for sale here.

Wm.F.Buckley. My Dad discovered him and

we watched and enjoyed his verbal skills

What a loss! Great article!.