Blog Post

The graveyards of Gallipoli

By Jonathon Van Maren

The Gallipoli Peninsula in January is quiet and empty. It is sporadically overcast, a bit nippy, and the perfect time to drive from place to place unimpeded by the hordes of tourists who descend on these sacred sites later in the year. My wife Charmaine and I spent a day driving along the coast from memorial to graveyard: from the beautifully sunlit Anzac Cove to the enormous monument to the war dead of the British Empire, looking out over the gleaming Dardanelles Straits. It has been over a century since the wind and the waves bore the sounds of death and gunfire, but it was here that the founding myths of two nations began, and so nationalist pilgrims still flock here to pay their tribute.

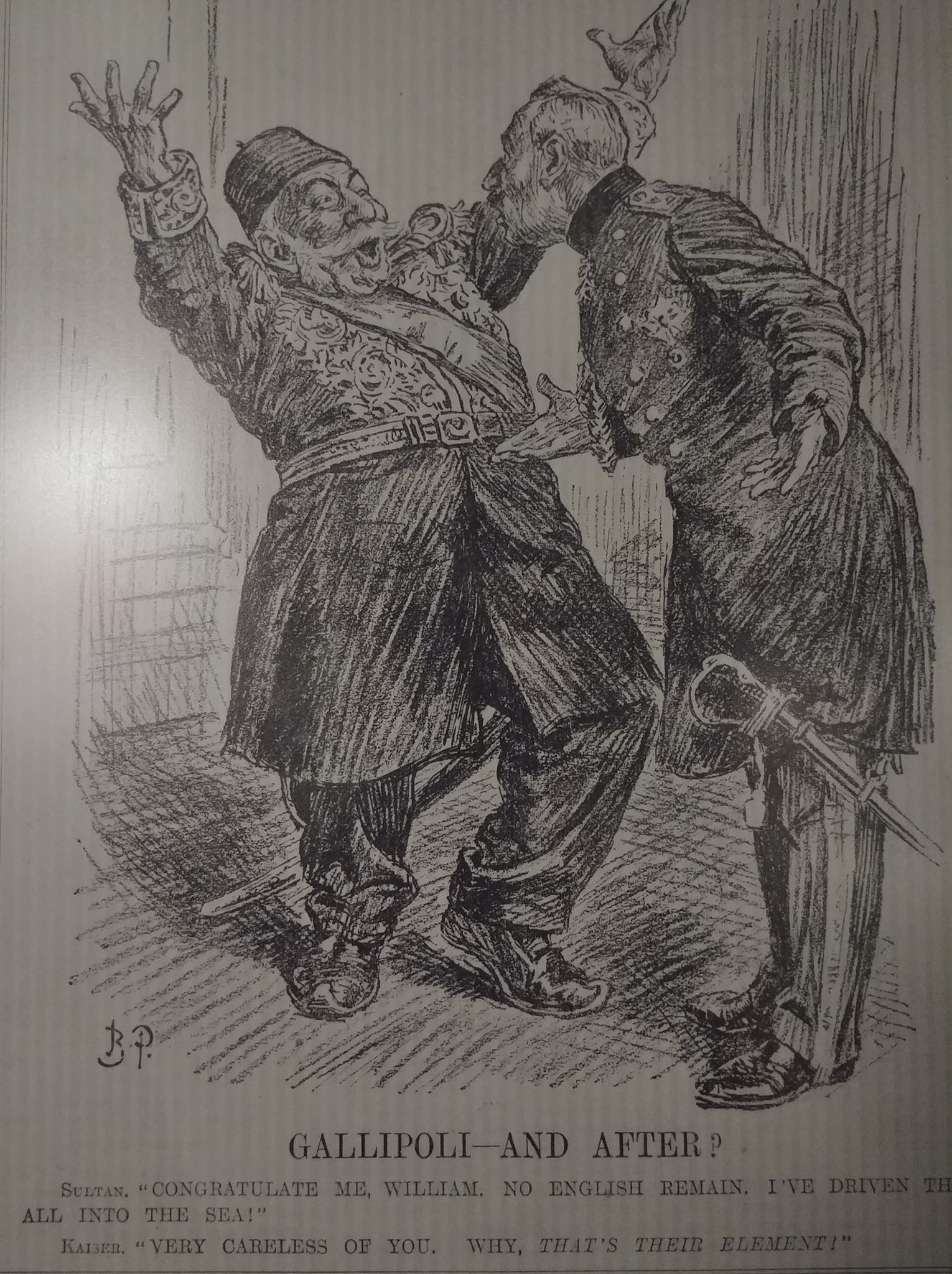

The ill-fated campaign, spearheaded by first lord of the British Admiralty Winston Churchill, began with a long-range naval bombardment from French and British battleships on February 19, 1915. With the Ottoman Empire joining the Great War on the side of Germany the previous November, Russia had appealed to the Allies for assistance in repelling a Turkish attack in the Caucasus, and it was decided that seizing the Dardanelles Straits (the slim passage connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara) could allow the Allies to connect with Russian forces in the Black Sea. Together, they could defeat the Ottomans from there. Signs that this might not be so simple came early: Within a month, three Allied battleships had been sunk by Turkish artillery fire and undetected mines, and another three were badly damaged. The region’s naval commander, Admiral Sackville Carden, suffered a nervous breakdown and had to be replaced.

It was decided to launch a land invasion instead. Lord Kitchener, the British War Secretary, appointed General Ian Hamilton to command the troop landings, with tens of thousands of French, British, Australian, and New Zealander soldiers gathering for the assault on the Greek island of Lemnos. Meanwhile, the Ottomans shored up their defences at expected landing sites under the command of German General Liman von Sanders. The attack commenced on April 25, 1915, with the Allied forces suffering brutal casualties but establishing beachheads at Helles and Gaba Tepe (which would later become known as Anzac Cove in honor of the Australians and New Zealanders who fought so courageously there.) Then, everything stalled, and the trench warfare that was grinding men to pulp on the Western Front commenced on the Ottoman one. Another major invasion on August 6 was initially successful, but fatal vacillating gave the Turks the opportunity to reinforce and it all ground to a halt once again.

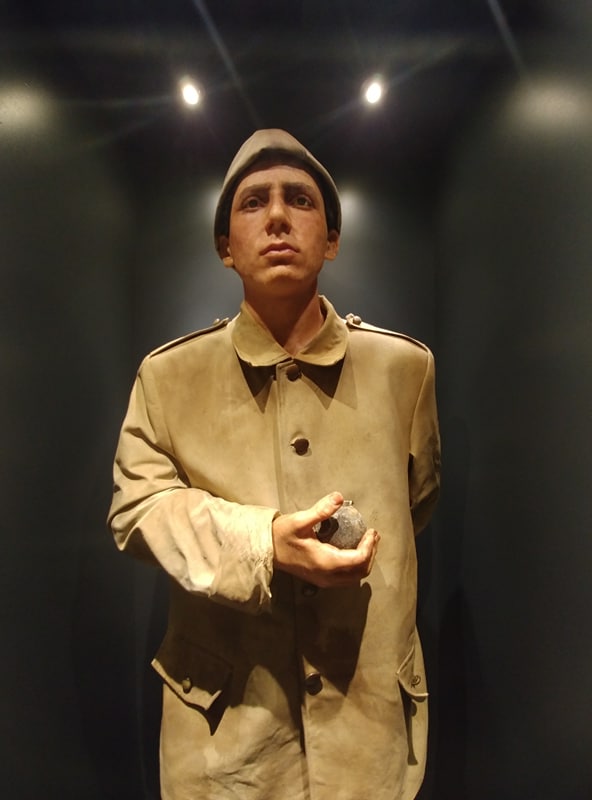

Hamilton and Churchill requested reinforcements, and were offered a mere quarter of the 95,000 they had asked for. Hamilton informed his superiors that an evacuation could cause up to fifty percent casualties, and they responded by replacing him with Sir Charles Monro. The evacuation was authorized on December 7, and the last Allied troops pulled out from Helles on January 9, 1916. They left tens of thousands behind. There were more than a quarter of a million casualties, and 46,000 men were killed. The Ottomans had suffered roughly the same number of casualties and lost 65,000 men. Their courageous defence of the homeland became the independence myth of modern Turkey: At the oddly-named Canakkale Epic Promotion Centre, a Turkish war museum, Charmaine and I were treated to an eleven-room film simulation that spent much time zooming in on handsome, swarthy faces looking determinedly at the foe, Mustafa Kemal bellowing orders like an orator, and ended with shots of Erdogan and a Turkish flag so large it filled an entire wall with a voiceover promising that Turkey’s future would be magnificent.

The Ottoman graveyards, too, are testimonies to the importance of the Gallipoli battles to modern Turkey’s national consciousness. One cemetery had hundreds of gravestones emblazoned with the crimson national flag of a country that did not yet exist when the men buried beneath them fell; They had been retroactively recruited to a nationalist cause for which they were needed. The scores of Turkish schoolchildren watching the well-done propaganda films of modern Turkey’s lightning progression from the “martyrs” of the Gallipoli trenches to Erdogan’s apparent diplomatic triumphs on the world stage (the simulation featured him next to U.S. President Barack Obama at a meeting of world leaders with a voiceover solemnly informing us how well-respected Turkey was in global affairs and how the nation’s star was consistently rising) seemed extremely impressed. The Australians and New Zealanders, too, have found a part of their own national identities in the valor and sacrifice of their soldiers who perished on the Peninsula.

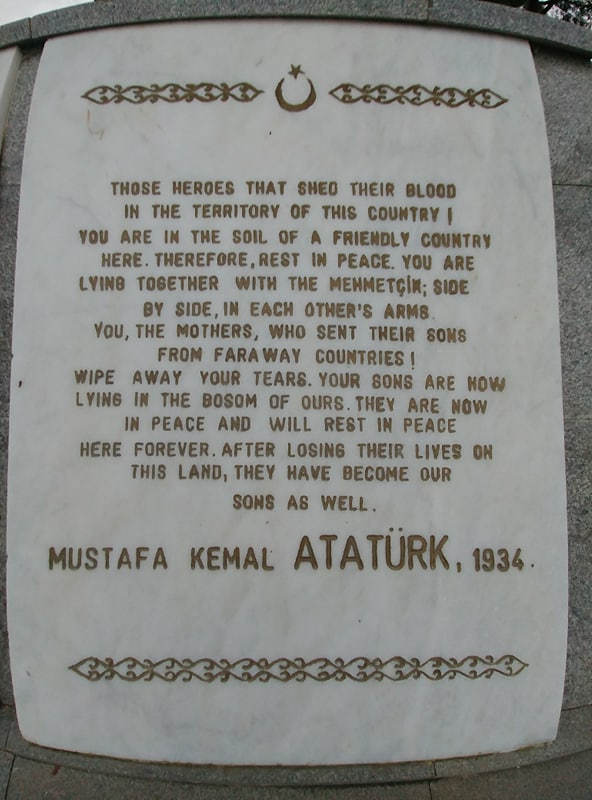

The mutual bloodshed has formed a strange bond between Turkey and her former enemies. Several variations of this speech exist—and some historians have called its accuracy into question—but the Turks have still chosen to carve the words attributed to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk to the mothers of their fallen foes in 1934 into a white marble plaque at the Canakkale Martyrs’ Memorial, where Charmaine and I found it as dusk fell:

Those heroes that shed their blood in the territory of this country—you are in the soil of a friendly country here. Therefore, rest in peace. You are lying together with the Mehmets; side by side, in each other’s arms. You, the mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries! Wipe away your tears. Your sons are now lying in the bosom of ours. They are now in peace and will rest in peace here forever. After losing their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well.

We decided to pull over at one small out-of-the way cemetery, Skew Bridge, when we spotted a marble monument in the shape of a cross and the words “Their Name Liveth For Evermore.” We climbed out of the car, and began to wander past the gravestones, reading them one by one. Most of them noted that the men recorded here were “Believed To Be Buried In This Cemetery.” They had all died within eight months of the landing in 1915. As always, each stone testified to what a cruel waste war is. Private F. Johnson, age 23, killed on July 2. We miss him most, who loved him best. Gunner P.L. Gibbs, killed on June 2 at age 20. No sorrowful speech, nor silent stone, can tell our loss, O hero son.

Reading the century-old inscriptions, the pain felt by the families of the boys who had come and died was as keen and sharp as if it were yesterday, although all those who once burned with love and bowed with grief are long gone. On the gravestone of W.S. Swain, a 23-year-old able seaman killed on July 5, two lines: Till the day break, And the Shadows Flee Away. Mother. On the somewhat newer-looking stone of Private A.E. James, killed on June 25: You died for your country, to become an unknown, only to be remembered, by us alone. On the marker for Sergeant C.H.R Henman, killed on July 29 at age 37: Beloved by wife, child, parents, brothers, comrades, and friends. The stone of Private A. Ferguson of the Highland Light Infantry, cut down on November 10 at age 26, brought sudden tears to my eyes: Who loved you best, They miss you most—loving wife & daughter Mary. Daddy never came home to little Mary, after all. He stayed in Gallipoli.

What struck me most as we slowly walked from grave to grave was the Christian character of the families that marked the resting places of their fallen loved ones. Many of the inscriptions read as if they come from another age, when we in the West still spoke a common language and possessed the same core beliefs about life and death and time and eternity. Some of them simply could not be understood by a young person in Great Britain, or Australia, or New Zealand today, like that of Private M. Mitchell of the Lancashire Fusiliers, killed August 7 at age 19: Watch and Pray. Or that of Private W. Harris of South Wales, killed at age 32 on December 4, three days before the authorization to withdraw was given: Thy will be done, O Lord. Or the headstone of Lieutenant A.C.M. Muir of the Scottish Borders, killed on October 27, also at the age of 19: Till He Come.

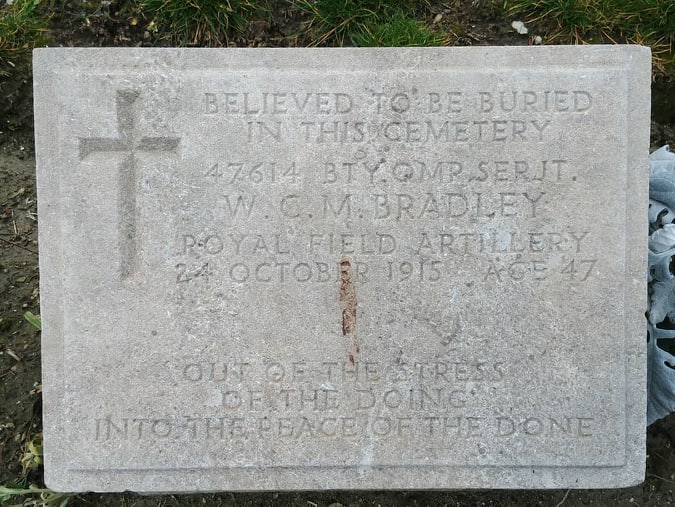

That there was life after death was still accepted almost universally. The gravestone of 47-year-old W.C.M. Bradley of the Royal Field Artillery, killed on October 24, reads: Out of the stress of the doing, into the peace of the done. And 19-year-old Private J.E. Anderson of the Army Cyclist Corps, killed on August 15: From the ground, There blossoms red, Life that shall endless be. And 20-year-old P.R. Brice, a member of the engineer’s division of the Royal Marines killed on July 25: This day the noise of battle, the next the victor’s song. And 32-year-old H.C. Evans, who entered eternity on June 5: He asked life of thee, and thou gavest him a long life. And able seaman J.S. Thomson, killed on June 10 at the age of only 17 years old: Fame shall live, while the earth remains, and shall pass to eternity.

The gravestones testified to the character of the countries that had called them to battle, and many praised the courage of those who fell. Private D.J.W. Buxton, killed four days after Christmas 1915: Their Glory Shall Not Be Blotted Out. W.H. Pountain, an engineer of the Royal Marines who was killed at age 21: Give us the grace to follow him, who duty’s path has trod. Private A. Prince, killed on July 15 at age 19: Mentioned in despatches. Shot rescuing a comrade. Thy will be done. And for 25-year-old Private L.L. Jenkins of the South Wales Borderers, killed on November 21, a simple epitaph: Duty nobly done.

Back at the hotel, I did some research, hunting online for the names I had read. I found Gunner Gibbs almost immediately. His full name was Percy Lennie, and on June 29, 27 days after he was killed, his “workmates of A.A. Lawson Process Engravers” posted a tribute to him in the Daily Telegraph: “A cheer and a smile and a wave of the hand; He wandered away into an unknown land. A better friend never lived. No one so good and kind. His equal in this weary world we very rarely find. He died a hero, fighting for his King and country. Greater love hath no man than this.” A photo showed a cheery, open face with a gap-toothed grin.

His “girl friends of the Gibbs Addressing Company” also placed a note in the Daily Telegraph on July 2, and his “loving Auntie Maude and cousins, Charles and Keith Harris,” noted that he “died a hero” in the Sydney Morning Herald. His “uncle, aunt, and cousins, Hugo, Janet, and Hilda Boati” inserted a note stating that he “died as he lived—honourably” in the same paper. So did an assortment of other relatives, friends, and loved ones. One fallen boy, marked by one gravestone—but mourned by hundreds back home. And so it was with each of these men who were fed into the meatgrinders of Gallipoli, never to return. Now they are all gone; not just Percy, but Auntie Maude and his work mates and girl friends and cousins. They are all gone, and it is up to us to remember what a senseless waste war really is—and that we will follow them into eternity some day soon.

Thanks for this. Have been following your articles a lot recently. I also spend a lot of time on Lemnos and have always wanted to visit Cannakale. War memorials are less compelling to me than the ancient sites – and now that I’ve read your account I may just stick with the Amazons and Argonauts. Nevertheless, this was very moving.

Thank you!