Blog Post

America versus the Evil Empire

By Jonathon Van Maren

My introduction to this series on the 20th century, “The Century that Changed Everything,” can be found here. Part I is “The World Before the War”. Part II, “How the Great War transformed Western civilization–and is still with us today,” can be found here. Part III, “The Second World War: Saving Christian civilization from Hitler’s Reich,” can be found here. Part V, “The Shoah: The murdered multitudes and the righteous few,” can be found here. Part VI, “An eyewitness to the birth of Israel and the Convoy of 35 speaks,” can be found here. This is the seventh installment in this series.

Unlike the turbulent events of the first half of the 20th century, most middle-aged Westerners today remember the half-century standoff known to history as the Cold War. Parents remember the duck-and-cover bomb drills in public schools, where shrieking alarms sent children skidding under their desks, covering their heads with their hands to ward off the impending atomic explosion. The fight against global Communism, which often took the form of hot proxy wars around the globe, shaped several generations. That is now just far enough in the past that the Millennials have forgotten all of that and are once again embracing the Marxist doctrines that racked up a kill count of several hundred million in the past century.

This trend is repugnant and often confusing to those who grew up behind the Iron Curtain. One cold, grey evening in Newfoundland, an hour or two outside of St. John’s in the middle of nowhere, I retired to the hotel lounge with a few of the audience members after giving a speech. One, a middle-aged Polish doctor, began to discuss life under Communism in his youth, punctuating his descriptions of the suffocating repression, rigged “elections,” and stifling of freedoms with sips of red wine. The rest of us, huddled on a few couches in front of a fireplace, listened with rapt attention, leaning forward as the ice cubes in our own drinks melted. At one point, a young female doctor whispered to us: “Aren’t we lucky to hear all this?”

We were, and I have had many such conversations with those who once lived in the Eastern Bloc. Because of their experiences behind the Iron Curtain, they are often inherently suspicious of government and susceptible to conspiracy theories because, as one told me, under Communism all of the conspiracies were true. The idea that the government line could be accurate was more laughable than any alternative because lies were the norm. Like Orwell’s Ministry of Truth, words either meant nothing or precisely the opposite of how they were employed. Interestingly, today’s Antifa thugs “fighting fascism” in black shirts on American streets have an eerie namesake: The Communists portrayed the Berlin Wall as protecting the imprisoned public from fascists seeking to pervert the “will of the people,” and East German authorities officially referred to the Wall as the “Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart,” or “Antifaschistischer Schutzwall” in German. The Antifa Wall, in other words.

***

I will be dealing with the Vietnam War in depth in a following essay, and I have dealt with the rise of the Soviet Union in previous essays. For the purposes of this column, I would like to begin by reviewing the Cold War in broad strokes. Like so many other phrases that encapsulated the post-War era, incidentally, the term “cold war” was coined by none other than George Orwell in his 1945 essay “You and the Atomic Bomb.”

For those of us born after the Berlin Wall fell or, like myself, are too young to remember the milieu of the Cold War, it is easy to forget that the decades between Nagasaki and the Reunification of Germany crackled with terrorist flareups and conflicts pregnant with the possibility of global catastrophe. Those of us who grew into consciousness in the 1990s arrived in an era of unprecedented peace. As Oxford historian Adrian Gregory told me during our conversation about the Great War, it is difficult to explain that era to our generation: “I grew up in the shadow of the atom bomb, but there was a moment between 1989 and the early 2000s where you actually did get to breathe and it didn’t feel like you were looking down the barrel of huge insecurity and potential extinction.”

It is one of the many ironies of the 20th century that Hitler and Nazism could only be defeated by the combined forces of democracy and Communism. By any standard, Joseph Stalin (“good old Uncle Joe,” for the purposes of Allied wartime propaganda) was as coldblooded a killer as Hitler and more prolific to boot. Despite Franklin D. Roosevelt’s relative gullibility regarding Stalin’s good intentions, the victors of the Second World War viewed one another with transparent hostility. The Soviets resented the US for long refusing to recognize them as members of the international community and held that the American delay in joining the war cost millions of Russian lives.

By the time the war ended, the policy of “containment” had already been developed by American strategists, famously encapsulated in diplomat George Kennan’s 1947 “Long Telegram.” The Soviet Union, Kennan noted, could not accept American hegemony, and tension and hostility inevitable as these two empires jostled one another like colossal tectonic plates, sending shockwaves rippling around the world. Thus, America needed to embark on a policy of “long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies.” That included, he told Congress the same year, supporting “free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation…by outside pressures.”

By 1949, the Soviets had successfully tested their own atomic bomb, prompting President Truman to launch the development of a hydrogen bomb. The first “superbomb” was tested on November 1, 1952, and the detonation produced a 25-square-mile fireball that vaporized an entire island and blasted an enormous hole in the ocean floor. Stalin promptly began his own H-bomb tests. Containment kicked off a massive arms race, with the US, Russia, and a smattering of other nervous nations stockpiling nuclear weapons capable of eliminating life on earth many times over. At home, the arms race shaped politics, culture, and reached into every aspect of daily life. Anti-communism would shape—and in many ways create—post-war conservatism. Hollywood pumped out films featuring apocalyptic nuclear devastation and inevitably Russian villains with appalling accents. Home bunkers were built, and schools practiced bomb drills. With these reminders, the stark fact that total annihilation might be moments away lingered constantly in the shadows of collective consciousness.

And then there were the spasmodic hot wars of the Cold War. The Soviets backed North Korea’s invasion of the south, and the West, led by the Americans, sent in troops and fought to an unsatisfactory stalemate in 1953. Two years later, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) admitted West Germany, triggering the formation of the Warsaw Pact, made up of the Soviet Union, Romania, Hungary, Albania, Poland, East Germany, and other nations, all committed to assist one another in mutual defence against the West. Castro’s Communist Cuba became a flashpoint as well, with JFK badly botching the would-be liberation of the island with the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion of 1961, and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis bringing the world to the brink of the unthinkable. The Vietnam War, of course, would change everything.

The Cold War also pushed the opponents to new heights, with the Space Race resulting first in the Soviet launch of the satellite Sputnik in 1957, followed by its American counterpart Explorer 1 the following year. The U.S. rushed to beat the Soviets into the New Frontier, creating NASA and pouring federal cash into the effort. Despite that, Soviet Yuri Gagarin beat American Alan Shepard into space by a month. The Space Race was seen as more than a strategic necessity by many Americans working in the Space Program—it was seen as a moral and spiritual imperative, as Kendrick Oliver lays out in his history To Touch the Face of God: The Sacred, the Profane, and the American Space Program, 1957-1975. The Soviet Union was evil, America was good, and the godless must not defeat the godly in this great venture. As astronaut Buzz Aldrin wrote at the time, “There are many of us in the NASA program who trust that what we are doing is part of God’s eternal plan for man.”

In fact, Webster Presbyterian, a church near NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center that served as a spiritual home for many of those working in the space program (and where Buzz Aldrin served as elder), would often feature sermons that grappled with related themes, such as “What would the discovery of alien life mean for Christianity?” There was even a hymn called “Bless Thou the Astronauts”:

When first upon the moon man trod,

How excellent thy name, O God.

The heavens thy glory doth declare;

Where-e’r we are, Lo! thou are there.

When Apollo 11 landed on the moon on July 20, 1969 and Americans set foot for the first—and thus far, only—time on another planet, several of them described it as a profoundly religious experience. Buzz Aldrin read from the Gospel of John and took Communion moments after landing on the moon’s surface, and before Apollo 11 headed back to earth, he read a second Bible verse aloud from Psalm 8:3-4 that he’d written on the same notecard: “When I consider thy heavens, the work of thy fingers, the moon and the stars, which thou has ordained: What is man that thou art mindful of him? And the Son of Man, that thou visitest Him?”

*******

In many ways, the religiosity of the Space Program was a microcosm of the standoff between the Soviet Union and the United States. For America, the Cold War was more than a high stakes duel between two ideologies jostling for global dominance. It was, fundamentally, a battle between the forces of darkness and light. President Ronald Reagan encapsulated that view in his famous speech to the National Association of Evangelicals in Orlando, Florida, on March 8, 1983:

Yes, let us pray for the salvation of all of those who live in that totalitarian darkness—pray they will discover the joy of knowing God. But until they do, let us be aware that while they preach the supremacy of the State, declare its omnipotence over individual man, and predict its eventual domination of all peoples on the earth, they are the focus of evil in the modern world …. So, in your discussions of the nuclear freeze proposals, I urge you to beware the temptation of pride—the temptation of blithely declaring yourselves above it all and label both sides equally at fault, to ignore the facts of history and the aggressive impulses of an evil empire, to simply call the arms race a giant misunderstanding and thereby remove yourself from the struggle between right and wrong and good and evil.

As America herself was roiled by the Sexual Revolution, the rise of feminism, and the counter-culture that would spread around the world (all of which will be examined in detail in later essays), a key source of American identity soon became rooted in the belief that America’s goodness was obvious in contrast with the Evil Empire. Despite this, the cultural shifts that shook America to her foundations during the Cold War would lead to homegrown evils, including the breakdown of the family, the corruption of culture, tens of millions of aborted babies, and plummeting church attendance. The very things that distinguished America so starkly from the Soviet Union were relentlessly under attack, sometimes literally so: In our post-9/11 world, it is also an oft-forgotten fact that continental bombings in America were, for a time, stunningly commonplace. In one eighteen-month period between 1971 and 1972, the FBI tallied 2,500 bombings in the United States—a rate of almost five a day. These bombings were largely ineffectual, although one January 1975 bombing of a Wall Street restaurant by left-wing radicals left four dead.

***

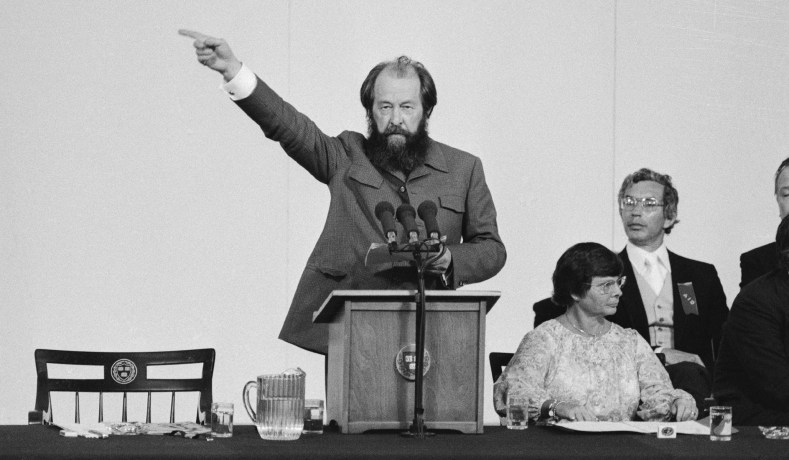

In the midst of all of this, one man who rose to prominence during the Cold War who could truly be called a prophet, relentlessly identifying the corrosive commonalities between the Evil Empire and the West. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn looked like a prophet, too—he had a long, flowing beard, and piercing eyes. His biographer, Joseph Pearce, described to me what it was like to meet the man: “He had very striking china-blue eyes. The thing about them was on the surface, they seemed very youthful, almost mischievous—that chuckle seemed to be there on the surface. But when you held the gaze, there was depths and depths of suffering and knowledge and wisdom there. It reminded me of the character of Treebeard in The Lord of the Rings, one of the oldest creatures in Middle Earth who has lived for thousands of years. He’s got this sense of humor, and yet his eyes are like a well of wisdom and experience. That is how Solzhenitsyn came across to me.”

Solzhenitsyn’s experiences are well-known. During World War II, he was thrice-decorated for his heroism as commander of a sound-ranging battery in the Red Army. Despite that, in 1945 he was sentenced to eight years in a labor camp for the crime of criticizing Stalin in his personal correspondence, a sentence cut short by Stalin’s death and Khrushchev’s subsequent reforms. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, a novel based on his experiences, was published in 1962. As he grew in prominence, Solzhenitsyn soon became too troublesome for Soviet authorities, and by 1969 he’d been expelled from the Writer’s Union. Nonetheless, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1971. After August 1914 and his famous recounting of the victims of Soviet totalitarianism The Gulag Archipelago were published in the West, Solzhenitsyn was arrested, stripped of his Soviet citizenship, and, in February of 1974, flown to Frankfurt, West Germany. After spending some time in Zurich, he moved on to Vermont in 1976, where he continued writing. He never stopped longing to go back—which, in 1994, he finally did.

When Solzhenitsyn first arrived in the West, he was fêted by conservatives, anti-Communists, and liberals alike. A literary giant who had turned his pen to exposing the Evil Empire, he was viewed as an instant ally. But it didn’t take long before many conservatives realized that Solzhenitsyn didn’t fit into their Freedom versus Evil binary so neatly. Rather than simply engaging in pro-Western machismo, Solzhenitsyn began critiquing Western society, too—and that did not sit well with his American hosts. While spending a weekend with Solzhenitsyn at his home near Moscow, Pearce asked him about the resulting accusations that he was “opposed to the West. Not at all, Solzhenitsyn told him: “No, I see Russia as part of the West. If the Iron Curtain had come down and the cream of Western civilization had come in over the top, I would have rejoiced. But the Curtain went up, and all the dregs of Western lowlife culture came in, and that’s what I oppose.” He didn’t see the Cold War as two-dimensional, Pearce told me. “It did keep Communism in its place, but it didn’t stop rampant materialism from undermining all that was good, true, and beautiful in Western civilization. The 1960s happened during the Cold War; the Sexual Revolution began during the Cold War.”

On June 8, 1978, Solzhenitsyn summed up ideological exile from both Communism and the West in his powerful and prophetic Harvard commencement address “A World Split Apart.” He condemned the inability of the West to understand that nations around the globe had much to offer from their own civilizations and values, and the fact that the West seemed to judge other cultures simply based on how far those cultures had progressed in the Western direction. He decried the passivity and cowardice of the Western elites. And then, he said this:

Western society has given itself the organization best suited to its purposes based, I would say, on the letter of the law. The limits of human rights and righteousness are determined by a system of laws; such limits are very broad. People in the West have acquired considerable skill in interpreting and manipulating law. Any conflict is solved according to the letter of the law and this is considered to be the supreme solution. If one is right from a legal point of view, nothing more is required. Nobody will mention that one could still not be entirely right, and urge self-restraint, a willingness to renounce such legal rights, sacrifice and selfless risk. It would sound simply absurd. One almost never sees voluntary self-restraint. Everybody operates at the extreme limit of those legal frames.

I have spent all my life under a Communist regime and I will tell you that a society without any objective legal scale is a terrible one indeed. But a society with no other scale than the legal one is not quite worthy of man either. A society which is based on the letter of the law and never reaches any higher is taking very scarce advantage of the high level of human possibilities. The letter of the law is too cold and formal to have a beneficial influence on society. Whenever the tissue of life is woven of legalistic relations, there is an atmosphere of moral mediocrity, paralyzing man’s noblest impulses. And it will be simply impossible to stand through the trials of this threatening century with only the support of a legalistic structure…Destructive and irresponsible freedom has been granted boundless space. Society appears to have little defense against the abyss of human decadence, such as, for example, misuse of liberty for moral violence against young people, such as motion pictures full of pornography, crime, and horror. It is considered to be part of freedom and theoretically counterbalanced by the young people’s right not to look or not to accept. Life organized legalistically has thus shown its inability to defend itself against the corrosion of evil.

According to Solzhenitsyn, the humanism and expanding libertarianism of the West had rotted out her very soul. Thus, those in the East were in some ways gaining spiritual things of greater value through suffering than all the material things the West had to offer. The West had abandoned her obligations in favor of her freedoms—the balance was gone, and the experiment, to his mind, was doomed. The West had everything but what was most important—a spiritual life, a fealty to the first things:

However, in early democracies, as in the American democracy at the time of its birth, all individual human rights were granted because man is God’s creature. That is, freedom was given to the individual conditionally, in the assumption of his constant religious responsibility. Such was the heritage of the preceding thousand years. Two hundred or even fifty years ago, it would have seemed quite impossible, in America, that an individual could be granted boundless freedom simply for the satisfaction of his instincts or whims. Subsequently, however, all such limitations were discarded everywhere in the West; a total liberation occurred from the moral heritage of Christian centuries with their great reserves of mercy and sacrifice. State systems were becoming increasingly and totally materialistic. The West ended up by truly enforcing human rights, sometimes even excessively, but man’s sense of responsibility to God and society grew dimmer and dimmer. In the past decades, the legalistically selfish aspect of Western approach and thinking has reached its final dimension and the world wound up in a harsh spiritual crisis and a political impasse. All the glorified technological achievements of Progress, including the conquest of outer space, do not redeem the 20th century’s moral poverty which no one could imagine even as late as in the 19th Century.

The reaction to the speech was immediate. The press, stinging from several pointed rebukes in Solzhenitsyn’s speech, called him an ungrateful exile, a “fanatic,” a “fierce dogmatic,” a “conservative radical,” and an “Orthodox mystic.” Interestingly, nearly all declined to publish the actual speech, preferring to snarl while they licked their wounds. As Solzhenitsyn wryly reflected: “When I called out ‘Live not by lies!’ in the Soviet Union, that was fair enough, but when I called out ‘Live not by lies!’ in the United States, I was told to go take a hike.” After the initial reaction, more thoughtful voices weighed in, grappling with the bitter truths Solzhenitsyn had laid out, wondering aloud if he might be right. An audience member published her own take, stating that Solzhenitsyn “challenged us; he bothered us; and he will stay with us.” Another columnist observed bluntly that: “He attacked the media for self-assurance, hypocrisy and deceit and they will never forgive him for it . . . Liberals usually blush at the word ‘evil’ [but Solzhenitsyn] has looked at one of hell’s faces.”

“Gradually,” Solzhenitsyn wrote later, “another America began unfolding before my eyes, one that was small-town and robust, the heartland, the America I had envisioned as I was writing my speech, and to which my speech was addressed. I now felt a glimmer of hope that I could connect with this America, warn it of what we had experienced, and perhaps even lead it to change direction. But how many years would that take, and how much strength?”

Forty-two years later, that question is with us still.

***

The presidency of Ronald Reagan was, for the Soviet Union, the beginning of the end. By the mid-1980s, the Soviet Union was far weaker and poorer than any of the experts realized, and to invigorate the stagnant economy Mikhail Gorbachev launched his twin policies of glasnost and perestroika. Glasnost was to usher in unprecedented openness, granting citizens new freedoms, abandoning book-banning, releasing political prisoners, loosening restrictions on the press, and permitting, for the first time, political parties other than the Communists. Perestroika was a series of reforms designed to restructure the economy by loosening the iron grip of the government. Gorbachev hoped that limited private ownership would lead to innovation and economic growth. Unfortunately for Gorbachev, the reforms all but destroyed the “command economy” that sustained the Soviet Union while the growth of the new market economy lagged. As Gorbachev later summarized it in his farewell address: “The old system collapsed before the new one had time to begin working.” Armed with new freedoms and saddled with rationing, food shortages, and endless lineups for every conceivable good, the Russian people grew angry and frustrated.

Gorbachev also worked to scale back confrontation with America. While Reagan increased defence spending, Gorbachev indicated that the Soviet Union was ready to put a halt to the arms race. Soviet troops were pulled out of Afghanistan and nations in Eastern Europe. And as with his other policies, things got worse before they could see fruit: the USSR’s alliances began to fall apart. First Poland revolted in 1989, demanding free elections. Later that year, East Germans attacked the Berlin Wall with sledgehammers and began flowing through the Brandenburg Gate while the stunned guards stood back. That November, the “Velvet Revolution” in Czechoslovakia topped the Communist government, and in December the Communist dictator of Romania, Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife were shot to death by a firing squad. Then, the Baltics began to declare independence from the Soviet Union, as well—Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania. In Lithuania, the Soviets pushed back—and then backed down.

The British journalist Peter Hitchens was one of the few Westerners who witnessed the collapse. He was, in fact, in Lithuania when the violence erupted. “I was in Vilnius, Lithuania in January 1991 and witnessed an incident that very few people know about because the first stages of the first Gulf War were taking place at the time, which is one of the reasons Gorbachev did what he did,” Hitchens told me. “The Lithuanian nationalists were being quite active in Vilnius, and suddenly troops were sent in and the morning I arrived they fired on the crowd. In the evening, they attacked some points inside Vilnius itself, particularly the television tower. I was present during some of that. They killed considerable numbers of civilians, and I saw the bodies in the makeshift morgue afterwards, which is how I know in detail what a human head looks like after a bullet has passed through it, an experience that has never left me since. They then gave a disgusting, lying press conference in which they pretended this action was justified and lied their heads off about what they’d done. I was furious and thought I was going to be arrested anyway because we thought they were going to round up Western journalists in Vilnius. In the end, they didn’t do it, but Lithuanian friends spirited us away from the hotels and put us up overnight to make sure we didn’t get captured.”

In the summer of 1991, the old guard of the Communist Party had finally had enough of Gorbachev’s reforms and resulting chaos. They launched a coup, placing him under house arrest and stating that due to “health reasons” he was not fit to be president. Then, they declared a state of emergency. Peter Hitchens was in the city when it all began.

“In the summer of 1991 when the anti-Gorbachev putsch came—which had some very strong support, the head of the KGB favored it, and they appeared to have part of the armed forces behind it—I was fortunate to be one of the very few Western journalists who was actually in Moscow when it happened,” he told me. “Most of them were on holiday abroad. By great good fortune, I had taken my vacation earlier that summer. The tanks actually came up my street, a grand street in central Moscow which had a lot of rather fine Stalinist apartment blocks on it. I thought: It’s all over. The hardliners have come back, they’re going to kill off this whole thing; we’re going to go back to the decrees of Communism. I thought it was going to be a Russian Tiananmen Square. But they lost their nerve and it collapsed with amazing speed.”

The tanks rumbling into Moscow were met by crowds linking arms and make-shift barricades. The chair of the Russian Parliament, Boris Yeltsin, mounted a tank and rallied the crowds. Three days later, the coup fell apart.

“The thing which I saw a couple of days later, after it collapsed—and I repeat this every time I’m asked about this and I’ll carry on doing it until it gets into public consciousness—was every single trash can in central Moscow—in those days trash cans were made of a sort of grey metal and they were urn-shaped—they were all full, and they were all giving off clouds of pale grey or white smoke,” Hitchens told me. “The reason for this, when I went closer, was because every single one of them was full of Communist Party membership booklets, red and gold, burning. All the people who had joined the Communist Party because it meant better jobs or better apartments or their children going to a decent university—whatever it was that had forced them to make their compromise with Marxism-Leninism which they didn’t want to do, they had all at that moment realized that this was over once and for all. In a great collective gesture, they all burned their Communist Party cards. I saw that.”

“A few months later, I was able to get into Sevastopol, the great naval station on the Black Sea,” Hitchens went on. “It’s a very beautiful place. The thing that I saw at that stage, about six months after the failure of the putsch, was in all the creeks and harbors and inlets, the warships of Sergey Georgyevich’s global navy, scuttled. Some of them down by the bow, some of them down by the stern, some of them half-tipped over sideways—but it was the wreck of a fleet. It was all over. It was a physical representation of a hugely important global political fact. It’s never left me. They couldn’t afford it anymore, apart from all other considerations. They had also lost the ideological drive that made it necessary.”

On December 8, 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev met in Minsk with leaders of Belarus and Ukraine and signed an agreement that confirmed their exit from the USSR. The treaty summed it up: “The Soviet Union as a subject of international and geopolitical reality no longer exists.” Eight of the nine remaining republics soon followed. On Christmas Day, the Soviet flag flew over the Kremlin one final time. The Cold War was over.

***

The 1990s brought an unprecedented era of optimism. The West had won, the pieces of a shattered USSR were crawling towards democracy, and the ending of the grand standoff had brought, in Francis Fukuyama’s famous rendering, “The End of History.” The countries of the former Eastern Bloc, mind you, were having a tough time of it. Hitchens told me that in Moscow in the winter of 1991, he witnessed a scene ripped straight out of Orson Welles’ The Third Man, “middle-class, educated people in a civilized city, selling their possessions. Their savings were wiped out, they’d lost their jobs. It was catastrophe.” One day, he predicted, the West will experience the same: “It hasn’t happened yet, and we’re very smug about it—because we don’t know what it does to you.”

It would be several years before the West realized what they had lost when their archenemy was finally vanquished. It became apparent—at least to some—that devoid of the values and the faith that had once animated the West, many had defined the West by what she was not—the Evil Empire. Communism and its evils had ironically become an enormous source of civilizational confidence for the West, buoyed by the leadership of transformational figures such as Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and Pope John Paul II. But when the Wall came down, Hitchens would later write, the ideology that had fueled the Soviet Union was no longer trapped behind a barrier of concrete and rebar. Western progressives no longer had the stinking albatross of the USSR to account for and could instead defend the ideology that had reduced millions to human rubble as the path forward for all mankind.

It was as if the West had been in an abusive yet co-dependent relationship with the Evil Empire, and when the USSR collapsed, there was relief, joy—and the sinking feeling that we no longer knew who we were. It would take a few years for the realization to hit, but the malaise was inevitable nonetheless.

There was one moment when everything seemed to snap into focus again: On September 11, 2001. When planes hijacked by Islamic terrorists and loaded with passengers and jet fuel smashed into the Twin Towers and the Pentagon, there was, in some quarters, an almost palpable relief. Old Cold warriors such as Christopher Hitchens, who had cut his teeth on revolutions in the Eastern Bloc and the good vs. evil battles of the Cold War, said as much explicitly: Finally, here was an enemy that we were not. The strange alliances between the neo-conservatives, left-wing Cold warriors, and conservative Christians that arose in the days following the attack on America were driven by the simple fact that all needed an enemy to fight. Many Christian conservatives, in the wake of the materialistic ‘90s and the Clinton presidency sounding the death knell of the Silent Majority thesis, had the sneaking suspicion that perhaps America was not as good as they thought she was. But here was a foe worth fighting and worth fulminating about. Here was an enemy that could unite everyone. The civic religion of Americanism could be recast with a different enemy, but one as totalitarian and brutal as the last one.

As we now know, it didn’t work out that way. The unity was short-lived; the wars were not. We should have learned lessons about Afghanistan from the Cold War, and Iraq from earlier in the century, but we did not. Instead of civilizational confidence, we now face unprecedented polarization, a real-time tearing of our collective social fabric, a wave of populist leaders rocking democracies to their core, and dozens of books and think pieces wondering whether Fukuyama had it all wrong—perhaps Western-style democracy isn’t the last stop on history’s train ride. As Ross Douthat pointed out in his recent book The Decadent Society, radical Islam may not be the civilizational threat we thought her to be, especially as the Muslim world appears too paralyzed by internecine conflict and civil war to conquer the weak but still-dangerous West. The threat of radical Islam briefly brought the libertines and the Christians together to defend the West—with each side producing its own set of dogmas and justifications for entering the fray—but as the War on Terror fades into background noise, the opposing factions have begun to suspect that the enemy lies within and act accordingly.

After all, if the barbarians are not at the gates, there’s nobody here but us—and we no longer know who we are.