Blog Post

Beverly Cleary: Chronicler of the lost world of the post-war American suburbs

By Jonathon Van Maren

Beverly Cleary, America’s oldest literary icon, died at the age of 104 on March 25, 2021 at the retirement home in Carmel Valley, California, where she has lived since 2016. Born Beverly Bunn in rural Oregon on April 12, 1916, to Presbyterian parents—her mother was a schoolteacher and her father was a farmer—her first memory was of the church bells of her hometown, Yamhill, clanging out the joyful news that the First World War had come to an end. She would become one of the most important chroniclers of the American suburbs following the Second World War decades later.

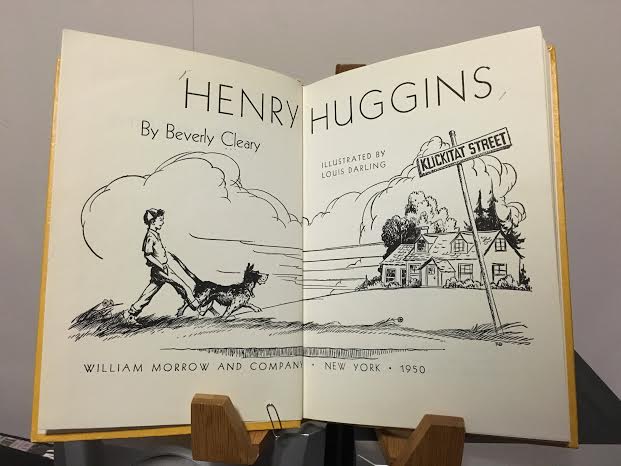

Cleary became an obsessive reader during her youth, heading off to Chaffey Junior College in Ontario, California, during the Depression before attending the University of California at Berkeley and the University of Washington. She eloped with her long-time beau Clarence Cleary in 1940, and her first book Henry Huggins, loosely based on stories she had overheard while working in the library of the U.S. Military Hospital in Oakland during the Second World War, was published in 1950.

The success Cleary would see over the next fifty years is almost unparalleled. Her books sold 91 million copies worldwide, and Cleary’s work would eventually be recognized with the 1981 National Book Award for Ramona and Her Mother, the 1984 Newberry Medal for Dear Mr. Henshaw, and in recognition of her contribution to American literature, she was also given the National Medal of Arts, the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal from the Association for Library Service to Children, and recognition as a Library of Congress Living Legend—and the list goes on. A school in Portland, Oregon near the Grant Park suburb where she grew up (her family moved there when she was six) where most of her books are set was named after her, and the park now features statues of her best-loved characters.

Five years after Henry Huggins was published, Cleary gave birth to her twins Malcolm and Marianne, whose antics would inspire some of the stories that would capture the hearts of children the world over. Cleary would become famous for writing back to the many children who sent her letters and would note in her later years that modernity had not been kind to childhood. “I don’t think I joined this century,” she admitted in one interview. “I think children today have a tough time, because they don’t have the freedom to run around as I did—and they have so many scheduled activities.” When she was young, she noted without judgement, “mothers did not work outside the home; they worked on the inside. And because all the mothers were home—99 per cent of them, anyway—all mothers kept their eyes on all the children.”

Because of the America she described in her books, Beverly Cleary became much more than just a beloved children’s author. She became an important chronicler of the post-war American suburbs, and the stories she wrote captured an era when unsupervised children roamed about, only heading home once the streetlamps switched on. This period, perfectly encapsulated by P.J. O’Rourke in the early chapters of his memoir The Baby Boom: How It Got That Way…And It Wasn’t My Fault…And I’ll Never Do It Again, lasted a full half-century, from the late 1940s until the late 1990s. Cleary’s suburban tales span the same time period—her first book, Henry Huggins, was published in 1950, and her last, Ramona’s World, was published in 1999.

Cleary could spend fifty years writing about the same characters in the same neighborhood because for fifty years, childhood experiences didn’t change all that much. I spent the first few years of my own childhood in a subdivision like the one where the Quimbys and Henry Huggins grew up, roaming more or less freely, yelling from the sidewalk to summon the neighbor kids, and enjoying summer afternoons that seemed to last for months. Kids could be kids back then, free of the smartphones and the accompanying pornographic poison that seem so omnipresent now. The worst that could happen was badly skinned knees and elbows from biking around the cul-de-sacs too quickly. Millions of children grew up like this.

Cleary’s books sometimes seem dated now, but that is a very recent development. When my mother first handed me Henry and the Paper Route (1957) in the mid-1990s, I felt that I could relate to Henry not only because Cleary had so skillfully captured the psychology of childhood, with all its great frustrations and little triumphs, but also because the setting was still genuinely familiar and many of the activities were still the same: the endless fascination with building things, creating elaborate games of make-believe, conquering the neighborhood. To create such a childhood now takes conscious decisions and the active rejection of a lifestyle charged by non-stop screens from toddlerhood to the teen years. A 2011 profile in the New York Times noted that Cleary herself has complained about the way screens have consistently grown larger in children’s lives, slowly eclipsing the childhood activities she rendered so well.

It is because the suburban way of life Cleary chronicled is rapidly disappearing that her work now often incurs nostalgia. Helicopter parenting, the rise of social media, and the ubiquity of video games and other screen-oriented activities have moved much of childhood indoors—and even outdoors, kids are often still glued to their devices. Children and teens between the ages of 8 and 18 now spend, on average, more than seven hours a day looking at screens, and this reality has reshaped the sounds and sights of subdivisions that once teemed with active children. When I first moved into a townhouse in a middle-class subdivision, I was stunned to realize, the day that school started, how many children lived in my neighborhood as they emerged to get picked up by the buses—most had spent bulk of the summer indoors, and the streets and sidewalks had remained eerily quiet.

In many ways, Cleary’s books are becoming cultural artifacts of a bygone time when suburban kids went fishing, annexed abandoned lots, built solid clubhouses with tools (and knew how to do so), and went exploring with their dogs. These days, when the average child sees hardcore pornography before they reach puberty, there is something achingly sweet about Cleary’s descriptions of a pre-digital time when boys found girls both endlessly interesting but frequently annoying and in the way. Holding hands for the first time, back then, was still a thrill that adults would be able to recall decades later. These days, children have sexual knowledge that most parents would not have had back then. Increasingly, this sort of innocence is more likely to be found in children’s literature than in their lives.

The times have changed so much that even admirers of Cleary’s work find her occasionally disconcerting. In 2019, one writer at LitHub celebrated her portrayal of a “simpler time,” when children wandered “their blocks without parental supervision” and “invented games instead of interacting with screens, where they held paper routes and could scrounge money to buy a bike at auction for $6” but bemoaned “moments of silly, antiquated sexism” such as when Mrs. Quimby compliments the neighbor boy for “fixing” Ramona’s trike by taking off the wheel, saying: “You must be very good with tools.” This amusing (and slightly confusing) complaint says more about the critic than the author.

Beverly Cleary’s characters are to American suburbia what Sterling North in Rascal or Billy Coleman in Where the Red Fern Grows were to the backwoods. They were quintessential children of their time and place, and they were also distinctly American: Henry Huggins is every bit as entrepreneurial as Tom Sawyer, and Ramona Quimby is animated by the same deep feelings and independence as Jo March. Interestingly, Cleary’s honest portrayal of children, with their squabbles and rebellions and struggles, has occasionally triggered debate amongst the homeschooling set as to the value of her work. I believe that an honest analysis places Cleary’s work firmly within the American canon.

For decades, millions of children saw their own lives reflected in Cleary’s work. I’m not claiming that Cleary taught any grand virtues in her books, although she did emphasize many small ones. That’s one of the reasons children loved them so much—they didn’t seem as if someone was trying to stuff lessons down their throats. But I am saying that her books are an important part of Americana in precisely the same way that Norman Rockwell’s paintings are, a record of our collective memory of what was, at least in my view, a better time. Cleary’s books are not only delightful stories that children still love. They are now more than that—they are a reminder of what childhood was, and what it can be again.

I am almost seventy years old, and I STILL love Beverly Cleary’s books. They are a refreshing delight to read.