Blog Post

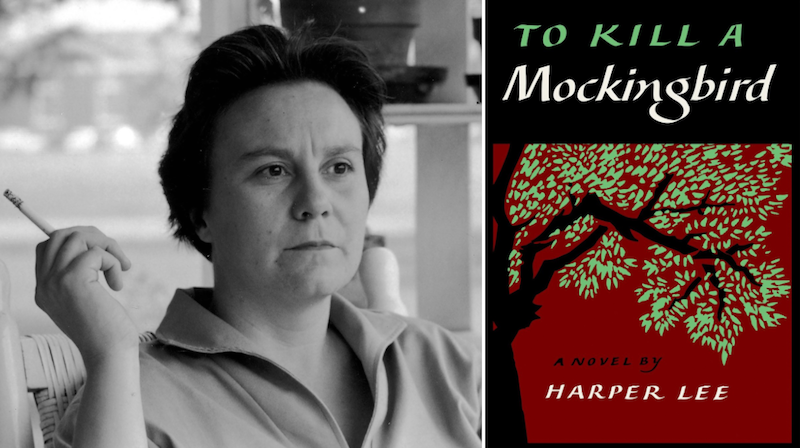

The last days of Harper Lee

By Jonathon Van Maren

“I think one could argue that To Kill a Mockingbird did for twentieth-century race relations, or at any rate for white attitudes toward blacks, what Uncle Tom’s Cabin did for white attitudes about slavery in the antebellum nineteenth century,” historian Wilfried McClay wrote fifteen years ago in First Things. “And yet it is rarely examined as a work of serious literature, not to mention one whose convicting force changed the moral life of the nation. And the book’s influence is probably not anywhere near being over. At least, one can hope not.”

That was then, and this is now. Despite being one of the greatest works of American literature, written by a woman from Alabama just as the civil rights movement was forcing an ugly and often bloody reckoning with America’s cruel race policies, the iconoclasts have set their sights on Nelle Harper Lee’s monumental novel. This month, a teacher in British Columbia was suspended for showing the film; a high-brow school in Los Angeles cancelled To Kill a Mockingbird as part of their “anti-racism” initiative; the American Library Association reported a few weeks ago that the novel was one of the most “objected to” of 2020. And that’s just this year.

Cancel culture has become the norm over the past half-decade, and Harper Lee—who died in 2016 in Monroeville, Alabama at the age of 89—lived to see it, although she said nothing publicly about it. She must have marveled at our profoundly stupid political moment. One can at least understand—although I disagree—with decisions to pull some novels by great American novelists such as Mark Twain for the racial attitudes in books like Huckleberry Finn, although Twain’s attitudes, too, were complicated and are not easy to categorize. Or at least, they weren’t.

Despite the publication of Go Set a Watchman in 2015, which is an earlier version of To Kill a Mockingbird rather than a new novel, Lee’s 1960 masterpiece must stand on its own as her response to the critics. An intensely private person, Lee refused nearly all interviews after 1964. She left Monroeville for Manhattan, only to return when her health required her to in her later years. Despite being awarded the 1961 Pulitzer Prize, she never wrote another novel. In 1964, she noted that she’d hoped for either “a quick and merciful death at the hands of the reviewers” or that “someone would like it enough to give me encouragement.”

What she got, she later said, was “just about as frightening as the quick, merciful death I’d expected.” She shrank from the publicity and despised the relentless intrusions into her life brought about by her unexpected success. She had, overnight, become one of the greatest American novelists of all time, but she refused to play the part. Besides her family, she allowed only a few close friends. One of them, Alabama historian Dr. Wayne Flynt, met her at a conference where they were both speaking in 1983. Lee hated public speaking, and only agreed to say a few words when she heard her former friend Truman Capote—Dill Harris in the novel—might be invited.

Flynt, who published Mockingbird Songs: My Friendship with Harper Lee a year after her death, got off to a rocky start with the legendary author. At the conference, she signed a book for his fourteen-year-old son, but when he asked her for an autograph she replied icily: “I only sign for children.” Despite that, the two began corresponding after she read an article on how her book had persuaded him to return to his home state of Alabama, and they eventually became friends. Flynt and his wife visited Lee often and were with her in the days leading up to her death. He was one of only a handful permitted to speak with her at the assisted living facility in Monroeville in her final days.

Lee, Flynt told me, was not shy or reclusive—just intensely private. “To us she was extremely social, extremely forthcoming, revealing all sorts of things about herself—except for the inner woman,” he explained. “I’m not sure anyone, even her best friends in Manhattan, knew the inner woman.” They frequently debated history; Lee was fascinated by the gruesome past of places like Murder Creek. “In a different life I’m not so sure Nelle would not have been the most famous historian who ever lived, because she was so graceful a writer and had an obsession with history.”

At one point, Lee told Flynt about her grandfather, who had been in the Fighting Fifteenth Alabama Infantry in the American Civil War. “He must have been at Gettysburg,” Flynt said. “Oh yes,” said Lee. “On the second day.” She described it all in vivid detail. The ones that survived, she said, were the ones that could outrun Chamberlain’s men, who were on their heels clubbing and bayoneting them to death. There was no neo-Confederate bravado with Lee—her grandfather had survived, she said, because he ran fast.

Her life growing up in 1930s Alabama was the inspiration for much of her novel. Her father Amasa Coleman Lee was the inspiration for Atticus Finch. She had played, as a child, with African American children who were sometimes the children of slaves.

But the novel destroyed more than her privacy—it also destroyed her childhood friendship with Truman Capote, author of the true crime work In Cold Blood, which Lee worked on as his research assistance. After the success of To Kill a Mockingbird, Capote became wild with jealousy that Lee had won a Pulitzer Prize and he had not. He even spread rumors that he’d written the book; the fact that Lee never wrote another caused suspicions to grow. Capote’s bitterness eventually destroyed him as he turned to drink, drugs, and promiscuity. “I don’t know if you understood this about him, but his compulsive lying was like this: if you said, ‘Did you know JFK was shot?’” Lee told Flynt. “He’d easily answer, ‘Yes, I was driving the car he was riding in.’”

“Lee hadn’t pushed him away,” Flynt told me. “He pushed her away.” Capote died in 1984 at the age of only 59 of drug abuse and liver disease.

With the publication of Go Set A Watchman, much was made of Harper Lee’s alleged dementia. In fact, Flynt says, she was mentally sharp until her death—but nearly completely deaf. Because of this, people often misunderstood her. After she had a stroke, for example, she would often go to sleep after lunch and if visitors arrived to see her, she would be curled up in the fetal position on the bed. A journalist, coming upon her like this, made much of her incomprehension upon being startled awake. These situations were embarrassing for her, Flynt said, and were part of the reason her lawyer limited access to her.

Her deafness did result in some humorous situations. On one occasion, Flynt and his wife took Lee to her favorite restaurant in Monroeville. Everyone, of course, recognized her—the town had only 6,000 residents—but people were generally respectful and would leave her be. This time, however, a woman came over while she was eating and told her that her mother had gone to the Monroe County High School with her.

“Nelle looked at me and said very loudly: ‘What did she say?’ and I said [it] loudly, so everyone in the restaurant could hear it,” Flynt told me with a chuckle. “Of course, everyone was listening now: ‘She said her mother was a classmate of yours in Monroe County High School.’ Nelle looked up and said: ‘Oh, what was your mother’s name?’” The woman said the name; Flynt repeated it very loudly. Lee said: “Oh, your mother was such a sweet lady.” The woman absolutely beamed with delight. “Thank you, Miss Lee!” and she turned to walk away. Lee, of course, was nearly deaf and thus spoke loudly without realizing she was doing so. Turning to Flynt, she bellowed: “Wayne, who the heck was that?”

Flynt completely rejects—and rebukes—the much-circulated rumor that Lee was too senile to give permission to publish Go Set A Watchman and that her lawyer was running her affairs. Flynt would know—he discussed it with her. When it was published, he went to visit and congratulated her on the new book. “What new book?” she replied. “I thought: She really is losing her memory,” Flynt told me. “I said: ‘Nelle, don’t play with us—Go Set A Watchman, your new book. And she grinned as broadly as she could and said: ‘That’s not my new book, that’s my old book!’” She hadn’t worked on the book for 55 years and joked to Flynt that she scarcely remembered what it was about.

According to Flynt, Lee was a child of the Great Depression and had received an offer that was simply too good to turn down. Her nephew had told her five separate times that she didn’t need to publish it, and at one point had even suggested that it wasn’t worthy of publication. It was Lee who said, firmly, that she was going to go ahead with it. Whatever people might have thought of Go Set A Watchman, Lee was sharp enough to approve its publication. To prove the point, Flynt shared a story from around that time. At a play shortly before she died—a performance of King Lear—she distracted the actors by repeating the words as the play went on. Flynt commented to her: “You could be King Lear!” “And you could be my fool,” she replied.

The next week, visiting her in the home, Flynt reminded her that the fool is always smarter than the king in Shakespeare. “Yes,” she replied with a sly grin. “But it took you a week to think of that.” She wasn’t demented, Flynt said firmly. Just misunderstood.

Nelle Harper Lee died on February 19, 2016. Wayne Flynt last saw her on February 7, 2016. They had a lovely visit, and she was still in high spirits. In one of their last conversations, Flynt congratulated her once again on the new book—nearly everyone in the world wanted to discuss her two novels. She was quiet for a moment, and then she said: “All I did was to write a book.” There was a long pause. “And it destroyed my privacy.” She said it again, later, when Flynt told her of an Australian boy with depression who had found in her book a reason to keep living. “All I did was to write a book,” she said tremulously. And then she was silent for a long time.

“To revisit [To Kill a Mockingbird] again is to reach back and experience the dawning of a sense of interracial good will and hopefulness and possibility that, at times, seems very remote today, even with all that we have achieved as a society in the intervening years,” Wilfrid McClay wrote. “[T]he moral world of Mockingbird may seem hopelessly innocent and idealistic, in just the way that Harper Lee’s admirable reticence may seem impossibly ascetic and futile in a publicity-saturated time. Mockingbird could not envision the immense harm that has been wrought in the years since by the cynical exploitation of race as an issue–not least, the damage done to precisely the willingness of the heart that Mockingbird helped bring about.”

But perhaps by making Harper Lee’s masterpiece mandatory rather than cancelling it, she can once again achieve in the hearts of the upcoming generation what she achieved in the hearts of their grandparents. If anyone can do it, the magnificent recluse from Monroeville can.

A wonderful work of fiction whatever the “cancel culture” says. It is just the sort of book we need at the moment, but the notion that folks can be awakened to their own prejudice and hatred just doesn’t work in the “anti-racist” climate we are in. Thank you for this insightful reminder of how this book influenced many of us in our “innocence.”