MAiD / Euthanasia

How assisted suicide destroys the loved ones left behind

By Jonathon Van Maren

This column was first published at First Things

The central argument for legal assisted suicide is that it alleviates suffering. But assisted suicide does not reduce suffering in society—it spreads suffering. We are not merely individuals, but members of families and communities. When we lose one of those members, especially prematurely, we all suffer.

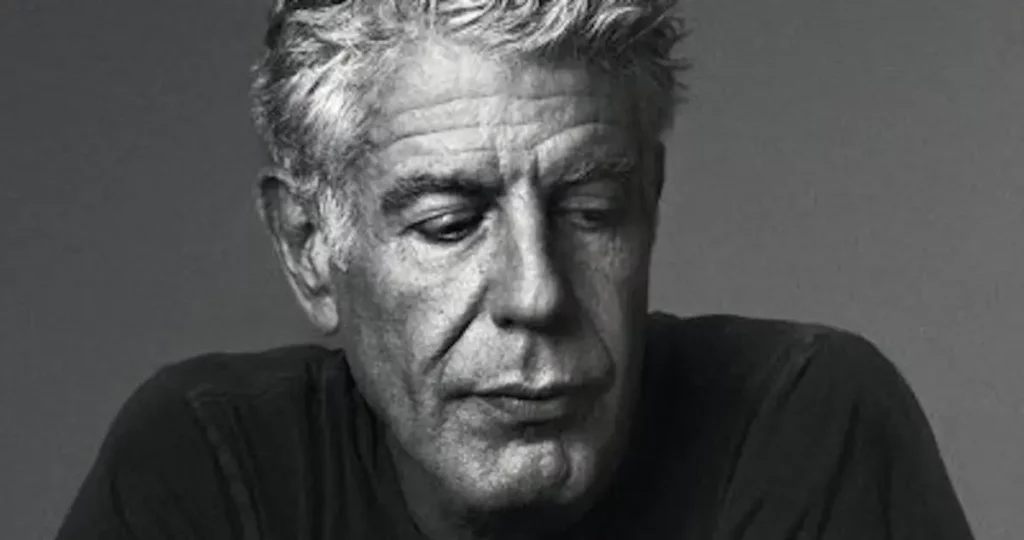

Morgan Neville’s 2021 documentary Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain portrays a wild life lived on the edges of human experience—lunch in the Sahara, dinner in Vietnam. Anthony Bourdain was the envy of millions when he hung himself in a French hotel room in 2018, and the film’s interviews with his loved ones are raw and rife with unprocessed grief and palpable anger that is visceral to watch. The documentary ends with heartbreaking shots of Bourdain’s little daughter, denied her father not because he did not love her, but because he did not want to stay. For Bourdain’s loved ones, their unbearable suffering began the moment they found out about his suicide.

Roadrunner strikes close to home because in Western societies, demands for the legalization of assisted suicide grow louder by the day, accompanied by a steady stream of horror stories coming from countries like Canada, where dying by lethal injection has already become common. The simple, central argument of the suicide activists is that the right to bodily autonomy includes the right to suicide, and that legalization is necessary in order to reduce suffering in society. The reality we see unfolding tells a very different story. Far from reducing suffering, assisted suicide has become the catalyst for spreading it. In many if not most cases, a death by lethal injection transfers temporal suffering to heartbroken loved ones who struggle to process what has taken place.

Gary Hertgers of British Columbia heard that his sister Wilma had died by lethal injection when her building manager called to tell him that the coroner had left her apartment. Wilma told none of her immediate family what she was planning to do, leaving them devastated. An Ontario father discovered that his daughter, who struggles with mental illness, had applied for assisted suicide—he and her mother, who have cared for her, are desperate to stop her. But suffering families are given virtually no consideration in Canada’s suicide regime. One son, a doctor, told the Globe and Mail that he still has nightmares about his father’s lethal injection, which the family opposed. Two daughters in BC found out by text message that their mother had received a lethal injection.

Sadness, anger, and even a sense of betrayal mingle with the grief of those who have lost, or are about to lose, a family member to assisted suicide. Their grief is compounded by the fact that there is nothing they could have or can do to stop it—even when they know it is scheduled. Not for nothing was the Globe and Mail’s report earlier this year titled “A complicated grief: Living in the aftermath of a family member’s death by MAID.” Some time ago, an Ottawa doctor told me that he has noticed a difference in the reactions of those whose loved ones die by lethal injection and those whose loved ones die naturally. The trauma and grief of the former is not unlike that of someone who has lost a loved one abruptly in a car accident—or worse.

In story after story, we see the central lie of suicide activists exposed. The claim that assisted suicide reduces suffering is not only false, but also disgusting and contemptible. Did the suicide of Anthony Bourdain—who, with his history of depression, would qualify for assisted suicide under Canada’s euthanasia expansion—reduce suffering because his life ended? What about the suffering of his little daughter? Or his friends? Or his other loved ones? Would any of them describe their suffering as “bearable,” or are they—like those left behind by the tens of thousands who have died by assisted suicide—merely forced to endure it?

Every one of us loves someone who has struggled with mental illness at some point in their lives. Most of us know someone who has grappled with suicidal ideation. Many of those closest to me have experienced this, and I shudder to think of the unbearable suffering I would experience if someone I love chose to end their lives in this way. Suicide activists, in their libertarian, hyper-individualist zeal, forget that human beings need each other, and that to offer (and even encourage) the sufferer to sever all bonds of love by state-facilitated suicide is to cause seismic social suffering. More than thirty thousand Canadians have died by lethal injection since assisted suicide was legalized to reduce suffering in our society. Instead, we have seen it multiply a thousandfold.