Abortion

The visceral power of abortion memorials around the world

On the green lawn of Resurrection Cemetery in Madison, Wisconsin, surrounded by gravestones, stands a breathtaking sculpture. It depicts a translucent, ethereal little girl of perhaps four years old walking, arms outstretched, towards a man and a woman. They are on their knees; the woman’s head is bowed, and her hand clutches her face. The man has one arm around her and reaches longingly towards the little girl with the other, his face gaunt, haunted, and stricken with grief. Created by Slovakian sculptor Martin Hudáček and placed in the graveyard in 2020, it is called “The Memorial of Unborn Children II” and was created as a place for parents who have had abortions to come and mourn and remember.

The statue, funded by donors, is a part of a series created by Hudáček to visualize post-abortion syndrome. He began his first sculpture on the subject a decade earlier. “I wanted to make a monument for unborn children,” Hudáček said. “I was praying, and many people came to me and said I need a picture of forgiveness.” Finally, he could visualize his creation: “It looked like a crying mother and a child who forgives her.” His first “Memorial for Unborn Children,” located in Slovakia, shows a mother on her knees, one hand clasped to her chest, the other holding her face. A small and almost transparent girl stands in front of her, reaching towards her face, hesitantly, not quite touching her. It is not only a scene from an artist’s imagination; many post-abortive mothers describe their children coming to them, years later, through the veil of dreams.

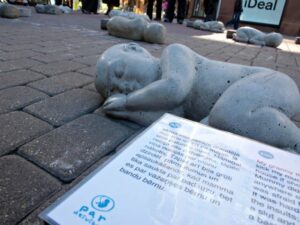

Hudáček is not the only one to portray the cost of abortion through sculpture. In 2012, those walking through Old Town Riga in Latvia encountered a strange series of sculptures laid out near the Laima’s Clock. Little babies were laid out in rows, twenty-seven in all. They appeared as if they were sleeping—some face-down, bottom in the air, the way babies often do; others curled on their sides, with their hands against their faces and their knees pulled up their chests. Beside each baby was a plaque explaining why the baby had died: “My mummy really, really wanted me but her friends pressured her and convinced her to kill me.” “My daddy demanded an abortion.” “My mummy experienced a negative attitude towards her pregnancy from everyone around her.” The statues had been placed there by the group “For Life” (“Par dzivibu”), which seeks to reduce the number of abortions in Latvia.

Many of the babies had red, yellow, and white flowers laid next to them—placed there not by the pro-life activists, but by passersby moved by what they saw and read.

I have seen a number of memorials to aborted children placed in cemeteries, but almost all take the form of headstones, some marking the place where babies rescued from dumpsters had been actually buried, some simply recognizing the absence of murdered millions. The most powerful memorial I have ever seen was a temporary one. I was in Philadelphia for the 2012 trial of Dr. Kermit Gosnell, an abortionist and America’s most prolific serial killer. He had killed thousands of babies both inside and outside the womb; he stashed some of their bodies in freezers and kept tiny severed feet in jars as trophies. Through the front window of his abandoned clinic, I could see chaos—filing cabinets tipped over, furniture in disarray. And along the windowsill, someone had fastened a long row of baby hands clenched into fat fists. Each was snapped off at the wrist. They were made of plaster and as white as the limbs floating in Gosnell’s jars.

Our culture badly needs such art. It is genuinely remarkable that so few artists have sought to portray the internecine drama of abortion. It is perhaps the most intimate form of human violence, bound up in love, hate, life, death, and the profoundly personal agonies of our sexual revolution. Abortion has existed since time immemorial, but it has been thousands of years since our civilization has produced so many tiny victims at such scale. And yet, the artists and storytellers of our culture rarely grapple with this subject—perhaps because to tell the truth about abortion is simply too painful and too politically inconvenient. We already have our fiction when it comes to this story—the fiction that these children are not children; that they do not really exist; that they were never really here, with us, their hearts beating just below those of their mothers and their souls present on earth. To admit this, even (or perhaps especially) in art, would be a salvo aimed at the heart of our society’s bloody mythology.

Powerful piece of writing.