Blog Post, Podcast Episodes

The Culture Wars Episode 12: Old-timers remember the real Laura Ingalls Wilder

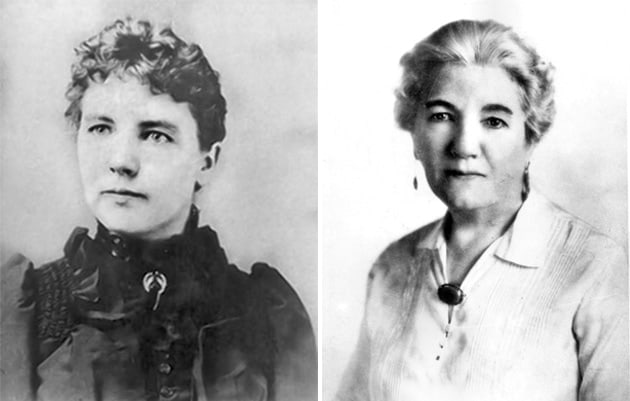

On today’s podcast, I spoke with several people who remember the real Laura Ingalls Wilder, Almanzo Wilder, and Rose Wilder Lane, decades ago when the Wilders lived in Mansfield. A fascinating link with America’s pioneer past:

My recent review of Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder:

There are now just a handful of people left alive who knew Laura Ingalls Wilder, and William Turner, the former chairman of the Great Southern Bank, is one of them. After stumbling across his name in Caroline Fraser’s powerful new biography Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder, I called the bank in Mansfield to see if I could track him down. After a few call transfers, Turner, now in his eighties, came onto the line. Of course he remembered her, he said. “When I was a senior in high school, we were having a pie supper to raise money for our class, and myself and a girl went out to see Mrs. Wilder at her place, Rocky Ridge Farm,” he chuckled. “And she said well, I can’t give you a donation, but I can give you a hand-written poem—and we sold that poem at the pie supper. I’ve forgotten just what it brought, but it wasn’t very much.” If only they’d waited a few years.

The woman who would become one of the most famous authors in the United States of America was then just another resident of Mansfield, Missouri, a thriving town that would fill up with horses and wagons each Saturday afternoon when the farmers would come to town to sell their crops in the square and the stores would stay open until 9’o’clock. “She was reserved, dressed nice and all,” Turner recalled. “As I remember, she was kind of a prim lady, very proper. I had a friend who lived on the farm next to her and he used to do things for her like mow her yard, and he said the way she’d contact him was she’d put a note in her mailbox, ‘to Roscoe,’ to come to her house. And then the postman would take it over to his box, which was the next box.”

A couple of days later, Bill Turner called me back. He had his friend with him in the office, he told me, and 92-year-old Dale Freeman, a retired newspaperman, had also known the Wilder family and wanted to share his memories with me. Freeman, whose father served as mayor of Mansfield, was one of only a handful of Catholics in the town, and “all four of us were micks.” Freeman used to sell Wilder magazines as a young boy, and “she paid cash, too—Colliers, the Missouri Ruralist. A nickel a copy…this was during the deepest, darkest Depression” He paused. “I guess I’m one of the final four or something that remembers Mrs. Wilder in the early days…She was a very nice lady, very polite. She was quite tiny, white hair, and I remember that the Methodist Church has a monthly luncheon. They’d charge a quarter or maybe fifty cents to go in and grab anything…She was quite a cook. I remember my mother saying Mrs. Wilder brought such and such so find where her food is and grab something from that. She was quite popular. She was quite active in the Methodist church—she was quite religious.”

Freeman remembered Almanzo Wilder, too, a quiet man who didn’t like to leave Rocky Ridge Farm if he could help it and preferred to stick to himself. “My dad played pool with him—billiards. My dad and my uncle ran the Ford Motor Company in Mansfield—this is at the start of World War II. I was the gas jockey. I waited on the pump. Mr. Wilder would drive up in his Chrysler, and at that time we had gas rations—this was in ’42. I would put in his four gallons of gas—which was the weekly ration—and Mr. Wilder and my dad would go over to the pool hall and shoot pool. I was just a kid, and he was an old man—everybody over thirty was an old man to me—he was always very nice to me. We didn’t see much of Mr. Wilder around the town square.”

It was somewhat surreal to be speaking with people who actually knew Laura Ingalls Wilder—after all, her very name conjures up the pioneer days of covered wagons, frontier towns, and a long-gone way of life. But history often isn’t as far back as we think, and Caroline Fraser’s beautiful book Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder does a magnificent job of bringing this fact home, combining an informative overview of the eras Wilder lived through with the small details of everyday life that made the Little House books so beloved in the first place. Fraser unearths many fascinating details about the Ingalls family, from their Puritan forebears who came over on the Mayflower to the fact that the events recounted in Little House on the Prairie actually occurred prior to Wilder’s memories of Pepin, Wisconsin, recorded in Little House in the Big Woods. Fraser traces the journey of the Ingalls family in vivid detail, adding many anecdotes not found in Wilder’s books: How she worked from the age of nine onwards to help support her family, the death of her little brother Freddy, and her father’s many financial failures, often borne of the fact that Charles Ingalls’ desire for both a profitable farm and his longing to live in the empty wilderness were profoundly incompatible.

Most riveting was Fraser’s recounting of the locust plague that struck the Ingalls claim at Plum Creek in 1875, wiping out their crops. Reading the book as a child, I had always assumed that this cloud of locusts was a local event—but Fraser describes in chilling detail an unfathomable horde of Rocky mountain locusts sweeping across America in an event of biblical proportions:

The Ingallses had no way of knowing it, but the locust swarm descending upon them was the largest in recorded human history. It would become known as “Albert’s swarm”: in Nebraska, a meteorologist named Albert Child measured its flight for 10 days in June, telegraphing for further information from east and west, noting wind speed and carefully calculating the extent of the cloud of insects. He startled himself with his conclusions: the swarm appeared to be 110 miles wide, 1,800 miles long, and a quarter to a half mile in depth. The wind was blowing at 10 miles an hour, but the locusts were moving even faster, at 15. They covered 198,000 square miles, Child concluded. “This is utterly incredible,” he wrote, “yet how can we put it aside?” The cloud consisted of some 3.5 trillion insects.

The swarms swept from Saskatchewan to Texas, devouring everything in their path. The grasshoppers savoured the sweat-stained handles of farm implements, chewed the wool off sheep, ate the leaves off trees. After flying, settling, consuming, and laying eggs, they began marching across the country, millions massing to form pontoons across creeks and rivers. Hoppers were said to “eat everything but the mortgage.” Terrified, people reached for comparisons, likening the insectile clouds to other natural disasters: snow storms, hail storms, tornadoes, even wildfires. “The noise their myriad jaws make when engaged in their work of destruction can be realized by any one who has ‘fought’ a prairie fire … the low crackling and rasping,” read a report from the U.S. Entomological Commission, created by Congress to address the crisis. Even modern scientists stretch for language to convey the swarm’s ferocity, calling it a “metabolic wildfire.” It consumed roughly a quarter of the country.

Farmers ran frantically to cover tender garden plants with gunny sacks, quilts, shawls, and dresses, only to watch, stunned, as the insects chewed right through them. A Kansas woman found denuded pits hanging from her peach tree. She tried to save her garden by covering it with sacks but soon saw it was hopeless: “The hoppers regarded that as a huge joke, and enjoyed the awning … or if they could not get under, they ate their way through. The cabbage and lettuce disappeared the first afternoon.” She noticed the “neat way” they had of eating onions from the inside out, leaving the outer shell behind.

Grasshopper carcasses fouled wells, polluted creeks and rivers, and halted trains labouring up grades, the tracks greasy with crushed bodies. There were reports of children screaming in horror as insects alighted on them and of farmers’ wives becoming hysterical, mad with fright. A woman wearing a striped frock said insects settled on her and ate “every bit of green stripe in that dress.” Technology was useless. Inventive farmers crafted “hopperdozers” out of sheet metal, contraptions drenched in coal tar and pulled across infested fields. These collected some pests, but their effectiveness was limited. Grasshoppers could work faster than fields could be dragged.

Pa Ingalls fought desperately to save his crops, setting fire to piles of straw and manure around the field to smoke out the invaders. After two days of struggle, he gave up, and on the third day the locusts headed west, marching up one side of the Ingalls shanty and down the other. In their wake, they left the fields and creeks filled with grasshopper eggs, guaranteeing that the farm would be a failure. In today’s money, the plague cost western agriculture roughly $4.6 billion, and two million bushels of wheat were lost in Minnesota alone that year. Pa was forced to walk two hundred miles east for work to make some money, and on November 30, was forced to sign a statement in the presence of county officials that he was “wholy without means” in order to get two half-barrels of flour for his family. Farrow suspects he never told his family how he got the flour.

There were other fascinating details not included in Wilder’s books, as well. On that famous night recounted in The Long Winter when Laura was teaching at a little school out on the Great Plains miles away from her parents in De Smet and Almanzo Wilder appeared out of the searing cold night to bring her home for the weekend on his sleigh, Almanzo had apparently been conflicted about whether or not to go and fetch her. The temperature had plunged to 45 below, and a stiff north wind cut through clothes like a hot knife through butter. As he stood hesitating in front of the hitching post in De Smet, wondering whether he should brave the frigid winter and bring Laura home, Cap Garland walked by. Giving him a glance, he uttered the comment that steeled Almanzo’s nerves and made up his mind: “God hates a coward.”

I had always wondered why the Ingalls family ended up staying in De Smet rather than carrying on—settling in town seemed so out of character for Charles Ingalls. As it turns out, Fraser reveals, Pa actually wanted to move on by 1883—this time, to the West coast via the famous Oregon Trail. His wife, however, had had enough. Caroline Ingalls put her foot down and refused to pack up and move yet again. Their travels were over, and Laura married Almanzo Wilder—he’d first asked if he could “see” her after a revival meeting–in the parlor of her friend Ida Brown’s house on August 25, 1885, with the Rev. Brown officiating. “Laura Ingalls’s childhood was over,” Fraser writes. “Her early life had engendered intense loyalty to family, a love of the open prairies, and a resentment of authority, tempered by a deep appreciation of kindness and helpfulness in others.” In a column written decades later in 1917, Wilder would lay out the philosophy that would inform her Little House books: “It is the simple things in life that make living worth while, the sweet fundamental things such as love and duty, work and rest and living close to nature.”

After the failure of the Wilder claim recounted in The First Four Years, where they had lost nearly everything—including a baby son, who is buried in the cemetery outside De Smet under a gravestone that simply reads “Baby Wilder”—the Wilders headed with their daughter Rose to live with Almanzo’s parents in New York State, before heading out again to try their hand in Florida in 1891. Laura despised it, and the venture lasted barely over a year. Back in De Smet, Rose described the contentment of the Ingalls family when they were all together—blind Mary, playing hymns on the organ on Sunday, and the satisfaction they derived from each other: “The truth is that they didn’t expect much in this world, and they just shed thankfulness around them for what they had.” But the Wilders would soon leave again, this time heading to the Ozarks in 1894 (a journey described in Laura’s published diaries, On the Way Home.) On their last night in De Smet, Fraser describes the heart-rending moment of their parting, when Laura asked Pa to play the fiddle for her one last time:

Long into the night, he spun out all the songs he had played to them across the years in their far-flung houses, in Wisconsin, Kansas, Minnesota, and Dakota Territory. “It was gay and strong and reaching,” Rose wrote, “wanting, trying to get to something beyond, and it just lifted up the heart and filled it so full of happiness and longing that it broke your heart open like a bud.”

When Pa finally put the fiddle away, he addressed his daughter. “You’ve always stood by us, from the time you was a little girl,” he said. “Your ma and I have never been able to do much for you girls as we’d like to. But there’ll be a little something left when we’re gone, and I hope, and I want to say now, I want you all to witness, when the time comes…I want you to have the fiddle.” All Laura could say was, “Oh, Pa,” and she wept as she and Almanzo walked back to their empty house across the moonlit prairie. It was a moment Laura would never forget, and Farrow says that it was one of the reasons she would later expend so much effort in to trying to recapture her childhood memories: To ease the ache of hearing Pa play the fiddle for the last time.

Pa died a few years later on June 8, 1902, at 3’o’clock on a Sunday afternoon. Laura, then thirty-five, made it back to De Smet from Mansfield in time to say goodbye. The entire town grieved him when he left, and eulogies described his pioneer life, which had crossed paths with the last wolves of the Great Plains, witnessed the banishing of the Osage, and endured the devastation of the locust hordes. In an odd twist of fate, the last living specimen of the Rocky Mountain locust that had destroyed Charles Ingalls’ farming dreams was found the year he died. It had suddenly gone extinct, for reasons that are still unknown to science. Laura began to write down her memories of her father shortly after he passed away, describing his eyes, “so clear and sharp and blue,” being swept up in his powerful arms, his big beard, and the sense of contentment that co-existed with his pioneer restlessness: he “cherished his wife, his children, and his music.”

Pa and the prairies: These, Fraser writes, would be Laura’s two great themes, and she would spend years at Rocky Ridge Farm in Mansfield attempting to recapture those vivid memories. She is now considered to be one of a handful of writers who truly brought the Great Plains to life, and Fraser also cites the riveting descriptions of Hamlin Garland, who similarly could never forget “the endless stretches of short, dry grass, the gorgeous colors of the dawn, the marvelous, shifting, phantom lakes and headlands, the violet sunset afterglow.” Garland’s words mirror Wilder’s, and anyone who has lived on the prairies (as I did for a time) will not only recognize but feel his renderings: “The winds were hot and dry and the grass, baked on the stem, had become inflammable as hay. The birds were silent. The sky, absolutely cloudless, began to scare us with its light.” On blizzards: “All was unreal, ghastly. No sky but a formless, impenetrable mass of flying snow; no earth except when a sweeping gust laid bare a long streak of blackened sod that had the effect, the terrifying effect, of a hollow, fathomless trough between hissing waves.”

Wilder’s career started off with columns in local newspapers, and as her daughter Rose Wilder Lane—who left home shortly after graduation, got married to a traveling salesman in San Francisco a few years later, and got rid of him in short order—built a successful (if complicated) career in journalism. Lane encouraged her mother to make use of her childhood memories, and some of Wilder’s first attempts to recapture the prairies are even more beautiful than the final published versions, like this excerpt from the original draft of Little House on the Prairie:

They watched the clouds in the sky and the wind blowing the grass over the prairie and were happy as they could be, thought they didn’t know just why. Perhaps it was because the world was so big and everything was so sweet. The very wind smelled good…never before had they camped in such a wild beautiful place as this.

One of the most moving passages from her original drafts is from the closing of the chapter after Pa and Ma had built their little house. Although the prose is not as polished as it would be in the final version, that moment over a century ago lives in her lines, and the scene is so real that one feels as if he is present:

The nightingale sang on and on. The cool wind moved over the prairie, and the nightingale’s song was round and clear above the grasses whispering.

At last the bird was silent. Laura and Mary had not gone to sleep, but they were very quiet. Pa and Ma sat motionless and still. The sky was like a great bowl of soft light overturned on the flat, black land.

Then Pa lifted his fiddle, settled [it] against his shoulder, and touched the strings softly across the bow. A few liquid notes fell like bright drops of water into silence, a hesitating, questioning call. A pause, and Pa began to play the nightingale’s song.

The nightingale answered him, the nightingale began to sing again. It was singing with Pa’s fiddle. When the strings were silent the bird went on singing. When the bird paused Pa called to it with his fiddle and it sang again.

The nightingale and the violin were talking to each other in the cool night under the moon.

Fraser’s description of the complicated personal and working relationship between Rose and her mother is fascinating, but obviously coloured by a transparent dislike of Lane, who struggled with mental illness all her life (the only child she had conceived with her husband was stillborn.) Lane, of course, eventually evolved from a globe-trotting journalist to a political writer fixated on the promotion of libertarianism (and an almost unreasonable hatred for FDR.) While Laura and Almanzo were not particularly political, Fraser notes, they were certainly conservative: When a government agent turned up at Rocky Ridge farm in 1938 to find Almanzo plowing a weedy stretch of their old apple orchard, the fastidious bureaucrat began to ask questions to determine whether Wilder was in line with government regulations. Wilder informed him that it was his farm, he was running it, and that the agent could make a note of that in his report while he fetched his gun from the house. The agent didn’t wait for Almanzo to return.

Some reviewers have criticized Fraser’s decision to spend so much time discussing Lane’s life in a biography purporting to deal only with Wilder, but the strange partnership between the two women and Lane’s eccentric and often outrageous life was probably too interesting of a subject not to linger on. Fraser says that decades after both women were gone, Mansfield old-timers were still talking about Lane’s unorthodox ways, and Dale Freeman told me that he remembers a bit of the chatter himself: “My mother and Rose were quite close because Rose and her companion, Helen Boylston—they called her Chub, she was quite chubby from what I recall—played bridge in a bridge club my mother and dad attended. I always thought the reason Rose liked to come to our house was because she could have a drink there. Rose went to school in Mansfield, and my father was in grade school at the same time Rose was. She was six or seven years older, but he knew her from the school days. I guess she was quite a pistol, even in school…I think there were still some old-timers who didn’t approve of Rose’s ways. And I don’t mean politically. She was one of those teenagers that when she left, everybody shook their heads.” Bill Turner’s analysis was shorter: “I remember people talking about her. She was kind of a strange, wild person. She wasn’t like Mrs. Wilder.”

Fraser also deftly disproves the assertion of Lane’s biographer that Rose’s contributions to the Little House books rise to the level of co-author, but she does claim that certain excerpts of Wilder’s work were probably inserted there by Lane, especially those sections that are more overtly political. One particular passage that draws Fraser’s critical eye is an inner dialogue Laura has with herself as she listens to a reading of the Declaration of Independence at a Fourth of July celebration in Little Town on the Prairie, a statement of principle that is utterly antithetical to the progressive worldview:

God is America’s king. She thought: Americans won’t obey any king on earth. Americans are free. That means they have to obey their own consciences. No king bosses Pa; he has to boss himself. Why (she thought), when I am a little older, Pa and Ma will stop telling me what to do, and there isn’t anyone else who has the right to give me orders. I will have to make myself good.

Her whole mind seemed to be lighted up by that thought. This is what it means to be free. It means, you have to be good. “Our father’s God, author of liberty—” The laws of Nature and of Nature’s God endow you with a right to life and liberty. Then you have to keep the laws of God, for God’s law is the only thing that gives you a right to be free.

That such a profoundly Christian view of liberty can be found in a children’s book has irked more than a few progressives, and Kevin Williamson of the National Review suspects that the conservatism shared by Wilder and Lane might have had something to do with the stripping of Wilder’s name from a prominent book award last year. Wilder’s religiosity, which Fraser also takes note of (the Bible she kept next to her chair was filled with markers denoting verses she found especially comforting), has also made her suspect in recent years, with at least one author (Wendy McClure of Wilder Life: My Adventures in the Lost World of Little House on the Prairie) reacting to Wilder’s Christianity almost angrily.

When Wilder’s books were finally completed—she never intended the manuscript of The First Four Years to be published, and it was only released after her death—she accomplished something truly remarkable: A self-conscious memoir of a period in American history that was irrevocably past, the pioneer days of covered wagons, sod shanties, and restless men and women on the move to dig their fortunes out of the prairie earth: There’s gold in the farm boys, if you’ll only shovel it out. For millions of Americans and countless others around the world, it would be a testimony to the beauty of the simple life—it was, after all, the love of family, faith, and a contentment with their lot that brought the Ingalls through it all. They never got rich, and neither Pa nor Almanzo ever succeeded at farming a homestead claim. But they had each other, and that was enough. Fraser movingly summarized it this way:

Laura’s books left out the shenanigans of Burr Oak and Walnut Grove, as well as her father’s debt and any of his failures. This was true to her, though—not fiction. He was always her hero. Her little brother Freddy, the only Ingalls boy, was left out, too. Her final novel was her last opportunity to spend time with parents long gone, her last word on a marriage that had begun with such joy and promise. Secure in the eternal present tense, the last thing Laura says to the reader is, “It is a beautiful world.”

Wilder could go no further. Her life story, reimagined as an American tale of progress, was uplifted by authenticity and suffused by an ineffable sorrow. But for the rest of her life, she was done with all that. She had restored the family fortunes, in fiction and in fact. She had said goodbye. “We are all here,” went the song the family sang in the darkest, coldest hours. In Wilder’s recreation of the past, they still are.

Almanzo Wilder died in 1949, and friends found the old man lying in his usual chair, with Laura clinging to him. “She just didn’t want to let go,” the friend commented. Laura Ingalls Wilder followed her husband on February 10, 1957, and was buried in a funeral service by the Mansfield Methodist Church, where she’d been a member, next to her husband in the local cemetery. In the coming years, her memories would enter the collective memory of America, and profoundly shape perceptions of the frontier and pioneer life. The impact of her work cannot be over-estimated, and historians are still arguing about where her stories fit into the history of the American West.

Wilder is often criticized for saying that her books were true, with historians pointing to where she changed the chronology and where she left details out, especially when they dealt with her father’s failures. But they are missing the point. Wilder meant that the soul of her stories was true: That poverty could be borne if a family loved each other as hers did, that the simple things made people the happiest, and that all the money in the world couldn’t buy a fresh breath of prairie air. Her family had been content in spite of all of their trials, and this gratitude was the foundation of their happiness. With her father’s strong arms around her, her mother’s comforting presence, and a warm fire crackling on the hearth, the howls of wolves just outside her cabin door were nothing to fear. Wilder wasn’t trying to tell us something about Manifest Destiny or libertarianism. She was trying to tell us something that our culture today desperately needs to hear: That our families are precious, and with them, we can bear almost anything.

This was beautiful. Laura’s books continue to give me strength to carry on. Strange to me how the views on freedom and being good could offend anyone. “ George Washington said: “Virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government,” and “Human rights can only be assured among a virtuous people.”

Benjamin Franklin said: “Only a virtuous people are capable of freedom.”