Blog Post

Does evangelicalism have a “toxic masculinity” problem?

By Jonathon Van Maren

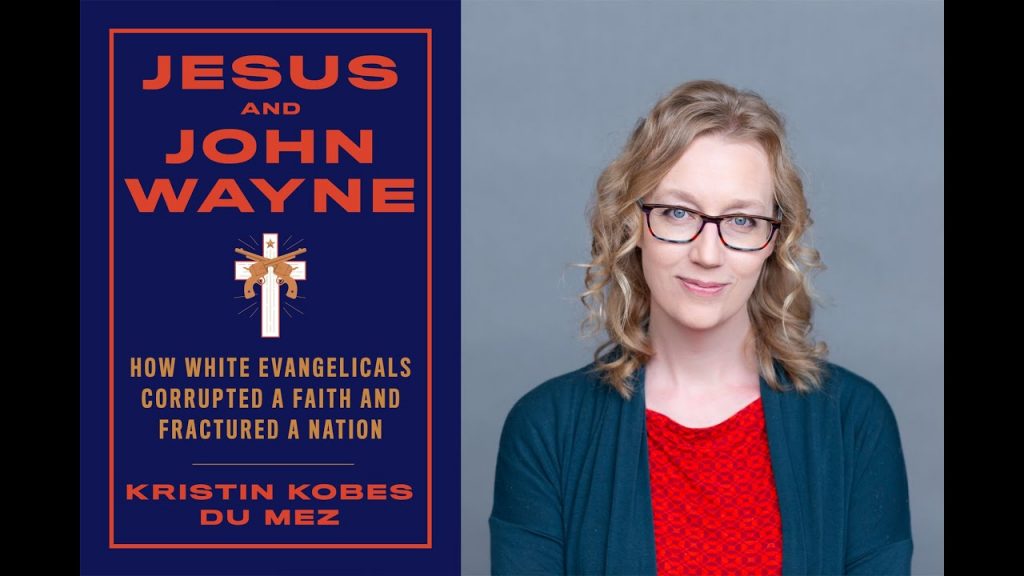

Published in May of 2020, Kristin Kobes Du Mez’s Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation has, as David French put it in his review, “ignited an enormous amount of argument and debate across the length and breadth of the Christian intelligentsia.” Du Mez is a professor at Calvin University and once attended a Christian Reformed Church; her theological and political positions are roughly what you’d expect from someone of this background, and her broadside against complementarianism (the idea that men and women are distinct from one another and correspondingly have different roles) clearly comes from the progressive Left.

Du Mez’s basic argument is that Evangelicals have been shaped by the culture (and she’s referring to white and predominantly Southern evangelicals here) as much as theology; that this fusion of culture and theology has produced a particularly aggressive vision of what biblical masculinity should be, replete with much revisionist backfilling about the character and disposition of Christ the Man. In conclusion, she avers that this made American evangelicalism ripe for both Donald Trump and a crisis of sexual abuse. This book was published before banners with “Jesus” written on them were unfurled at the January 6 Capitol riots, so Du Mez missed her most effective metaphor. The next edition will be sure to include a new foreword.

I’ll start with what Du Mez gets right. One of her most interesting observations is the extent to which capitalism has leveled the boundaries between denominations and different religious traditions by mass Christian markets that created a shared Christianish culture that supersedes doctrinal distinctions. Whether or not you define yourself as evangelical (and many Reformed denominations would not), you probably grew up with Dr. Dobson books in the house; books on Christian living, Christian fiction; Christian financial advisors; and maybe even CCM (Christian Contemporary Music). These created—and are still creating—a homogenous culture that inevitably breaks down the barriers between different denominations, often to the dismay of denominational leaders.

While Reformed, Southern Baptist, mainline, and various versions of megachurch evangelicalism have traditionally had vastly different cultures, these Christian markets have created a shared culture that has frequently shifted the center of influence away from local church leaders and paved the way for the creation of the “Christian celebrity,” which has done enormous damage over the past decades as men and women largely unaccountable to a local Christian church wield outsize influence over a growing ecumenical audience. Du Mez runs through the familiar list of televangelist scandals; the Ravi Zacharias revelations would be a recent example. The Internet, too, has done much to decentralize and democratize Christianity and undermine traditional authority structures with profoundly mixed results.

Du Mez is also correct in her critique of much of evangelicalism’s caricature of masculinity that insists on a specific version of machismo, although I think this is as much of a cultural Southern/American phenomenon as an evangelical one. In The Little Way of Ruthie Leming and other writings, Rod Dreher of The American Conservative—who is now Orthodox but grew up a nominal Methodist in Louisiana—writes extensively about the narrow version of masculinity permitted by Southern honor culture and how, as a more sensitive teen disinterested in hunting and sports, he struggled to define himself. Kevin Roose (now of the New York Times) also described this culture of Christian masculinity in his 2010 book-length undercover investigation of Liberty University under Falwell Sr., The Unlikely Disciple: A Sinner’s Semester at America’s Holiest University.

Du Mez’s accounting of evangelical literature on masculinity is detailed but not nuanced. Because she is obviously writing from a pro-choice, feminist position, her critique is an attempt at demolition rather than balance. Much evangelical rhetoric about Jesus and the disciples as manly men is not only ridiculous, but has often sounded extremely disrespectful to me, and it is easy to cherry-pick jarring and cringeworthy quotes. I once attended a Saturday night barbeque hosted by a church in Florida on a pro-life trip where a huge bodybuilder did party tricks such as bending a steel bar into a Christian fish while shoehorning various religious messages into his shows of physical prowess, and it was hard not to find the whole thing cartoonish. In short, these phenomena have more to do with culture than Christianity, although Du Mez’s examination of the feedback loop is interesting and even occasionally helpful.

David French, who has been carefully documenting sexual abuse in the church, is largely critical of Du Mez, noting that she lumps in anyone who believes in complementarianism with those guilty of real abuses. She obviously has a theological axe to grind, and has written a new history of evangelicalism around a thesis that is, to her, clearly as ideological as it is theological—Du Mez uses feminist terminology throughout, and it is often confusing when she uses the word “patriarchy” in an ideological sense while quoting her targets using the same word but intending it in the biblical sense. As French put it in his review:

Du Mez is correctly describing a strong strand of Evangelical culture. The desire to defend the nation in the Cold War, the desire to defend the country post 9/11, and the desire to defend masculinity itself from radical leftist and/or feminist attack combined to create (in some quarters) an obsession with an almost caricatured version masculine strength…Here is the key insight Evangelicals can and should take from the book. If you simply add a dose of Christian seasoning and language to an aggressive, secular conception of masculinity—and then marry that aggressive, secular masculinity to religious doctrines of male leadership—the result is disaster. Obsession with male power (rinsed through scriptures misused to manipulate and subjugate not just women, but every person subject to the male leader) manufactures abuse.

I wish someone who wasn’t a progressive had written this book—a lot of her more valuable critiques will be written off due to her insistence on dismissing the genuine concerns of Christians out of hand. She describes culture war concerns with dripping sarcasm; refers to threats to religious liberty in a matter that indicates she believes Christians are simply being bigoted; she understandably mocks Trump’s claims to faith while noting solemnly that the Clintons are genuine, practicing Baptists. Apparently it is okay to ignore accusations of sexual assault when it is convenient to your thesis. She also lumps everyone in together; to Du Mez, The Deplorables’ Guide to Making America Great Again by Todd Starnes is no different than R.C. Sproul’s The Dark Side of Islam. Too many times, Du Mez tips her hand—and it undermines her case.

The greatest flaw in Du Mez’s book is that she largely takes for granted (or at least seems to) that conservative evangelicals are insincere. Pro-life activism is about patriarchy, not concern for the lives of pre-born babies; fears about a secularizing culture and the sea change in values are ginned up by cynical leaders looking to consolidate power rather than people who truly care about the state of the family and the nation. Du Mez manages to make nearly everything about “whiteness” and “patriarchy” no matter how much historical context needs ignoring, and it badly damages her case. Du Mez’s critique comes from ideology rather than orthodoxy or even theology; highlighting inevitable hypocrisies does not lend credibility to her feminist claims. If her purpose in this book was to persuade evangelicals to reconsider their stances rather than preach to the choir, it will be dead on arrival for most.

As an analysis of how evangelicalism and American culture have shaped and reflected each other, Jesus and John Wayne is an interesting read. But I wonder who her intended audience is. It has been well-reviewed in secular publications traditionally eager for this sort of analysis, and many high-brow Christian publications have given Du Mez her thoughtful due. But the truth is that there are real conversations about the handling of sexual abuse, the necessity of victims’ voices, and the nature of “Christian celebrity” that need to be had. Du Mez, however, will view that discussion from the outside looking in when or if it happens—her determination to portray evangelicals as not only mistaken on masculinity but on abortion, religious liberty, LGBT issues, Islam, and nearly everything else—and her defence of progressive Democrats interspersed throughout—will ensure that most will simply write her off as an ideologue.

Du Mez is right that nuance is often profoundly lacking in cultural Christianity and evangelicalism. It is unfortunately almost totally absent from her book, as well.