Blog Post

Finding his Voice After Mumford & Sons: An Interview with Winston Marshall

By Jonathon Van Maren

“I’ve just finished reading two books by Klaus Schwab of the World Economic Forum, and I am appalled,” Winston Marshall told me. “They must be resisted at all costs. Unfortunately, if you criticize Davos, you come across as conspiratorial. Honestly, you’ve just got to read their books to see how abhorrent their ideas are. It’s a new religion that must be resisted. I’m writing about Davos and Klaus Schwab at the moment—it’s something I’m really appalled by.”

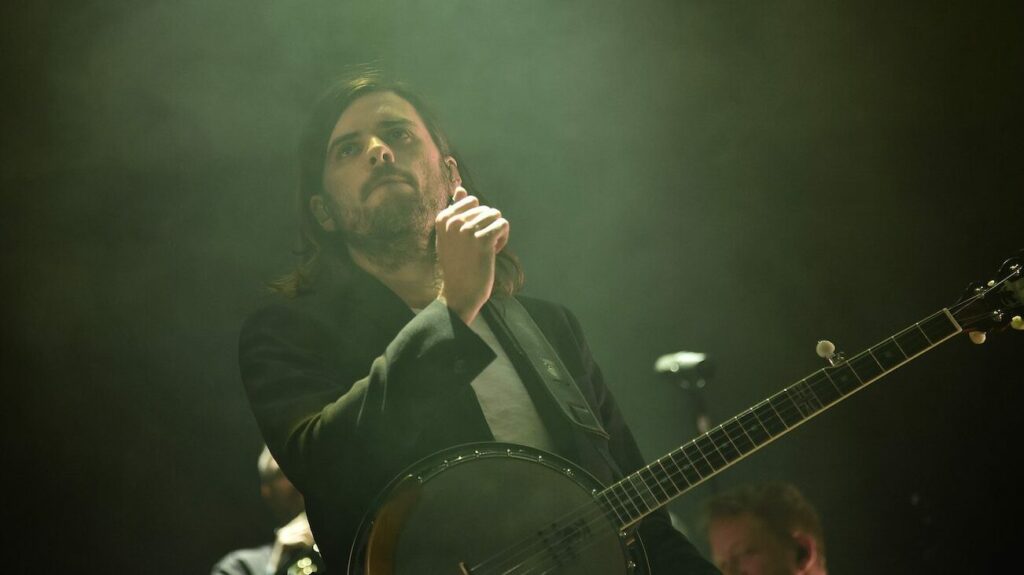

For Marshall, a banjoist, political writing is a career switch. For over a decade, he was a superstar in the music world, the co-founder of the folk-rock phenomenon Mumford & Sons. “Music transcends politics—it’s about connecting on a deeper level. That’s the role of art,” Marshall observed. Music may transcend politics, but the music industry certainly does not—and nobody knows it better than Marshall. In March 2021, he sent out a tweet complimenting journalist Andy Ngo’s exposé of Antifa, the New York Times bestseller Unmasked. It went viral, and people went nuts. Many, as it turned out, were livid at the idea that a musician would even read a book critical of the far Left.

It shouldn’t have been a story—“banjo player likes book”—but it was. Stunned, Marshall first apologized to protect his bandmates from the bizarre backlash. Then, in June, he announced on Medium that he would be leaving Mumford & Sons. Marcus Mumford has said that he “begged” Marshall not to leave, but Marshall felt that there was little choice. “I don’t feel like I really had a decision,” he told me. “My options were to stay in the band [and not be able to] speak my mind … probably [having] to lie—the apology hung around my neck and really affected my conscience. When I eventually told the band my predicament, there wasn’t really an objection. So I left.”

It was a big decision. Marshall was a key part of the band’s meteoric rise and received a Grammy and two Brit Awards for his efforts. For years, he’d taken the stage in front of tens of thousands of people; headlined Glastonbury; watched the artists from the posters on his boyhood bedroom wall turn into colleagues, even friends. “There were surreal moments,” he recalled. “Playing with Bob Dylan at the Grammys. He was almost a fictional character before that. How sweet Robert Plant was—he just treated you like one of the lads. Getting to play with Neil Young, and Elton John.”

They were playing to sold-out crowds of 20,000 people a night and travelling with a crew of hundreds. “It was champions league level.” He was walking away from a career many musicians would kill for. And ironically, while other artists had long used the stage as a political platform, Marshall had never been interested in doing so.

“I’m not saying there’s not [a] place for that, but certainly when I was with Mumford & Sons it wasn’t political at all—at least my participation in the band wasn’t political.” His political evolution began with the 2015 Manchester arena bombing at the Ariana Grande concert. “We’d played the Manchester arena a couple of times before, and we played it again after,” he told me.

When that happened it really felt like it was at my doorstep. I was very emotionally affected by it. That set me off to really understand Islam—I started reading the Koran, the Hadith. I noticed most of the music industry went off on this low-definition love-not-hate path. It was probably the first time I felt at odds with the political position—if I were to generalize—of the creative industries.

Still, he wasn’t particularly conservative.

I spoiled my ballot on Brexit because I couldn’t decide at the time—but even that was a pretty unique position in the music industry, where everyone is overwhelmingly anti-Brexit. By that period, I did feel like I was diverging from the thinking of my peers generally speaking. … That part of it comes down to a psychological level.” At that point, he thought he’d be playing with Mumford & Sons for decades before the blowback to a single tweet changed everything. “The whole period was distressing and confusing and certainly surprising. I saw my life crumbling all at the same time.

Now, however, Marshall is finding his voice. He’s a talented writer and has launched a Substack and a podcast with The Spectator, featuring interviews with Jordan Peterson (whom he admires enormously), composer Ignat Solzhenitsyn (whose father Aleksandr’s admonition to “live not by lies” is a guiding motto for Marshall), and pugnacious political writer Sohrab Ahmari. “I’ve been able to rebuild my life, so I don’t want to sound down because as difficult as it was then, I’m very much through it, and I lived to tell the tale,” he said. He’s working on music and plans to continue doing live shows—while also drawing attention to the causes he cares about.

One of those causes is exposing the vision of the World Economic Forum, as laid out in Klaus Schwab’s books The Great Reset and The Great Narrative, whose sinister vision is rendered banal by the bland, bureaucratic prose. “What’s appalling about The Great Reset is that Schwab says globalization, sovereignty, and democracy are not compatible with each other, and then makes a defence of globalization,” Marshall noted. “There’s this sort of loose implication that someone needs to be in charge—‘global governance’ and ‘elite leadership.’” The Great Narrative, meanwhile, is “essentially a new Bible” in which Schwab tried to “create new morals and a new moral framework based on collective agreement on climate catastrophe.”

READ THE REST OF THIS COLUMN AT THE EUROPEAN CONSERVATIVE