Literature

Resisting the ‘Machine’: An Interview with Peco Gaskovski

In the last two decades, dystopian novels and their cinematic spinoffs have flooded the market. Many of the novels—Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games, Veronica Roth’s Divergent series, etc.—are, in my view, largely derivative of Lois Lowry’s The Giver, a brilliant novel infused with what struck me as obvious religious overtones and a scathing critique of the commodification and cheapening of human life, all done allegedly in service of the common good. When I asked Lowry about this some years ago, all she said was that she hadn’t intended to project her own religious or political views onto the story, although she admitted that it was a subconscious inevitability.

Dystopian storytelling is all the rage at the moment because it is tapping into something many of us feel but often cannot articulate—much that is good, true, and beautiful is being kept from us. Most dystopian tropes explore common themes: the sense that things are being hidden; that the elites are against the common people; that those in power are acting against fundamental human interests; and, perhaps most importantly, that technology is being used to render populations subservient. In nearly every instance, those imposing tyrannical regimes on the masses believe they are doing so for their own good. As C.S. Lewis noted: “Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of the victims may be the most oppressive.”

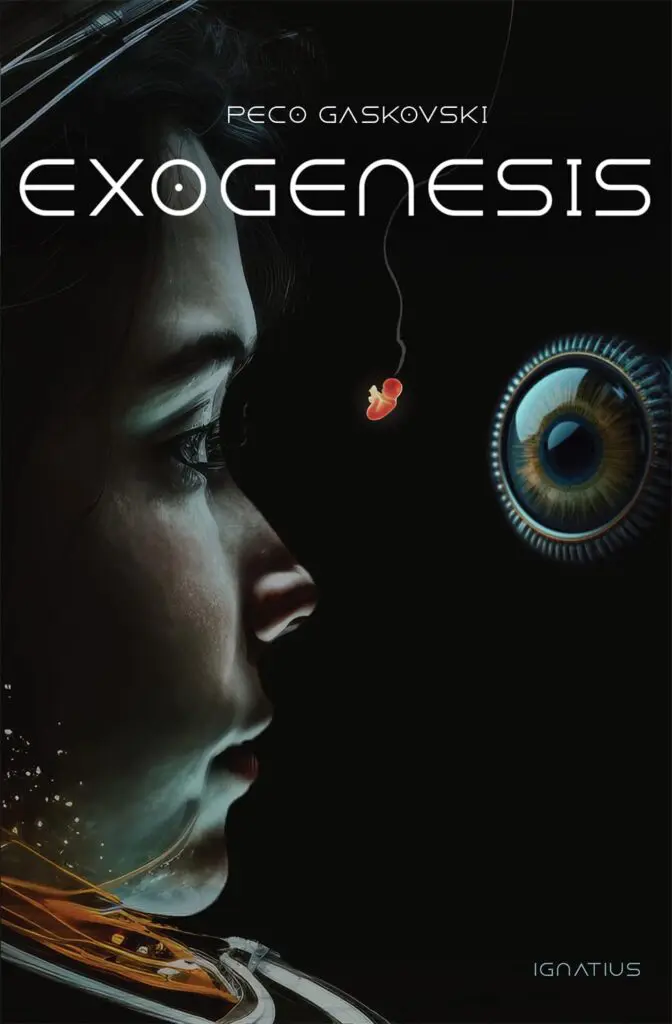

Peco Gaskovski’s new novel Exogenesis checks those boxes—and more. It is not a subtle novel. The story is based in Lantua, a “glittering thousand-mile metropolis where drones patrol the sky and AI algorithms reward social behavior.” It is the state that rose after the collapse of “Old America.” Citizens who conform to the regime are rewarded with staggering privileges; the poor struggle to rise through the “echelon system”; the population is rigidly controlled. Exogenesis refers to the process of growing embryos—selected carefully for genetic quality—in artificial wombs. Women do not give birth naturally in Lantua, and it is illegal to do so. Suffering is eliminated by the targeted use of therapeutic drugs. Human beings have in many ways merged with technology.

Outside Lantua, however, reside the Benedites, a rural religious people modeled on the Amish (their name a derivative of Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option.) The one-child policy meant to both limit the population and control their numbers is enforced at gunpoint. The main character of Exogenesis is Field Commander Maelin Kivela, who oversees the forced sterilization of Benedite teenagers with coldblooded efficiency. Kivela is totally committed to the technological civilization that grants her so many pleasures and privileges until a violent encounter with Benedite insurgents forces her to reconsider many of her assumptions—and in doing so, provokes similar reconsideration on the part of the reader. Gaskovski’s novel is a pointed cultural critique, but not a simplistic morality tale.

Peco Gaskovski took the time to answer my questions for TEC on his novelistic debut as well as his other writing projects. I sincerely hope to see much more from him.

What is the philosophy underpinning your Substack newsletter, Pilgrims in the Machine?

The newsletter always hovers over the same ground—what it means to be human in the lengthening shadow of technology. What does it mean to be human when our mental focus is constantly fed through the paper shredder of our devices and our distracted minds are manipulated by algorithms? What does it mean to be human if our lives are online and our real relationships suffer? How might AI and biotech further impact or distort the essentials of human identity? I don’t have a formal philosophy. I write as a father who wants to protect his children and family, and as a person of faith who wants to protect his mind and spirit. I’m looking for hope.

Seventeen hundred years ago church leaders gathered to formulate the Nicene Creed, to stabilize our basic understanding of the Christian faith. Today I feel like we need a further creed, one that outlines the parameters of being human—which is a strange thing to say. It’s always been taken for granted that we know what a human is. But old assumptions are being uprooted. Transhumanism, or the idea that we ought to transcend human nature and perfect ourselves through technology, is seeping into our way of thinking. Two decades ago, Wendell Berry wrote that the next great division in the world would be between people who wish to live as creatures and people who wish to live as machines. That division is getting closer, and if it comes, the impact on human identity will be shattering.

You’ve written much about ‘The Machine.’ How do you understand this concept, and how has it changed and shaped the way you live your life?

In most every sense the ‘Machine’ is a cautionary concept: beware of the dark side of technology. I sometimes imagine the ‘Machine’ as a many-armed destroyer goddess: the arms are Big Tech, investment, political interests, transhumanist ideology, and credulous consumers.

I should say, I’m not anti-technology. I believe that as God is a primary Creator, we are sub-creators who desire, and should, reshape creation through invention. Sub-creation includes things like art, writing, music, and architecture, but it also includes technology and innovation.

The problem arises when our sub-creations—in this case tech—displace the Creator. This doesn’t happen because people are suddenly bowing down to their MacBooks or singing hymns to their iPhones. It happens because we are religious creatures by nature. Our spirit yearns for ultimate meaning and purpose and connection. When God is displaced from the center of our hearts, the yearning doesn’t go away. It seeks something else. For many that something else is technology.

I don’t think technology can satisfy that yearning, but it can provide a counterfeit experience that stimulates our passions and validates our egos. How do we respond to this? How do we stay human and centered in a true reality? I’ve been asking myself these questions for years. Exogenesis is one answer in fictional form.

Your first novel, Exogenesis, is a disturbingly familiar look at one possible future. Is it your view that such a society is likely in the future, or have you created a literary parable to force readers to confront their relationship with technology?

I think it’s more the latter. The story is really about the present, disguised as the future, and some of the things we need to think about to avoid a technological dystopia. So, while like most novels there’s a plot, characters, and evocative settings—think Blade Runner meets the Amish—ideas are also quite prominent. That was a deliberate choice for me. I wanted the vital issues to be accessible, and for readers to come away from it not only feeling and imagining, but thinking.

For instance, the world of Exogenesis includes artificial wombs, the selection of human embryos based on polygenic profiling, the dissolution of mother, father, and family, and mass surveillance by artificial intelligence systems. All of these are future possibilities within our own world, some already emerging, and we need to be thinking about their moral implications now, rather than waiting for them to overtake us.

READ THE REST OF THIS ESSAY AT THE EUROPEAN CONSERVATIVE