Culture

The Nazi Hunter

First published on June 23, 2014 on The Times of Israel (Link: http://blogs.timesofisrael.com/the-nazi-huntge/).

I think every young boy with awareness—however muted—of World War II, especially those of us who grew up hearing stories about it from our grandparents, have imagined what it would be like to hunt Nazis and bring them to justice. Nazis are, to Western culture, the most deliciously unambiguous manifestation of evil that we can reference, which is perhaps why, as I discovered when I entered university, so many university students still feel compelled to fall back on the comparison in academic debates.

The reality of Nazi-hunting is markedly different from the delusions of grandeur that spring up in boyhood imagination (and doesn’t involve sticks and garbage-can-lid shields to boot.) Bringing Nazis to justice today, Dr. Efraim Zuroff tells me from Tel Aviv, Israel, is about historical detective work often involving years of excruciating research.

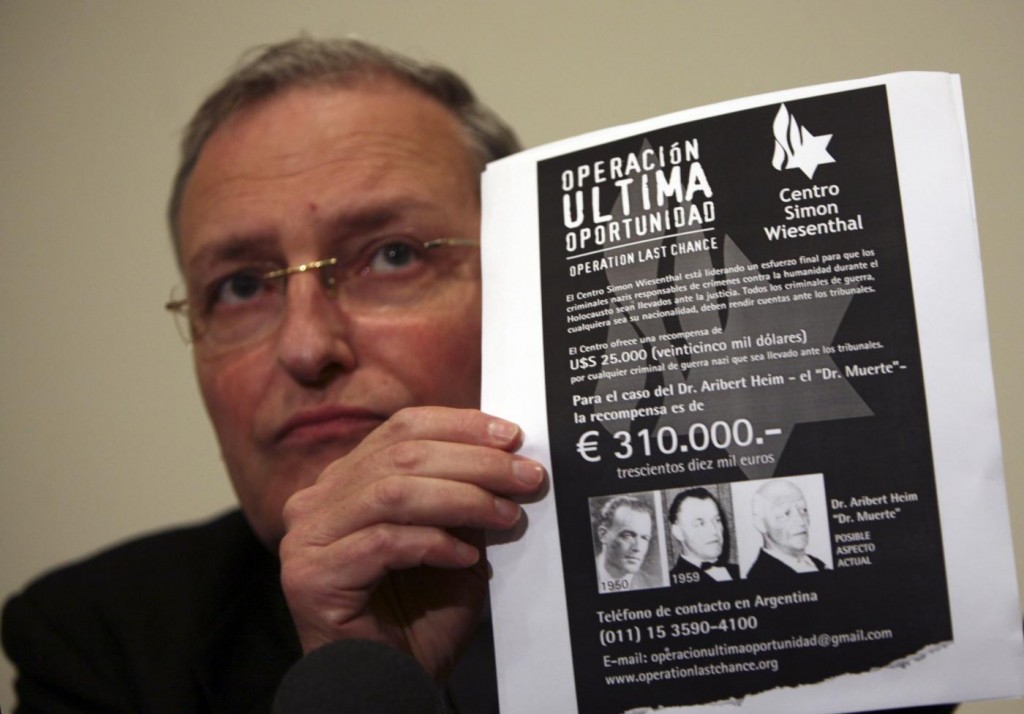

Dr. Efraim Zuroff is the top Nazi-hunter for the Simon Wiesenthal Centre and boasts an impressive resume. A historian with a Master’s degree in Holocaust studies, he has used thousands of historical documents, old interview transcripts, and decades-old archives to identify Nazi war criminals, track them down, and bring them to justice. His detective work has assisted in building cases against countless aging Nazis from the United States to Lithuania, and in 1995 he was invited to Rwanda to assist local authorities there in tracking down the perpetrators of the Rwandan Genocide. While lecturing around the world, he now advocates for “Operation Last Chance,” the Simon Wiesenthal Centre’s last-ditch attempt to capture and prosecute elderly war criminals.

“Most of my work is really regarding the efforts to find Nazi war criminals and facilitate their prosecution all over the world,” Dr. Zuroff tells me by phone, “We’re also very involved in the fight against Holocaust distortion and anti-Semitism, primarily in Eastern Europe, post-Communist Europe. When someone asks me what my job is, I say one-third detective, one-third historian, and one-third political lobbyist. In other words, I have to find people, locate them, bring evidence to build a case against them whether that’s witnesses or and/or documents, and I very often am involved in trying to create political will in countries which don’t want to prosecute Nazi war criminals. And unfortunately, most of the countries in the world do not want to do so.”

Indeed they don’t. Nazi war criminals have proven to be quite the embarrassment for most governments—for some, because they are a reminder of the no-so-distant past when atrocities were committed on their own native soil, aided and abetted by collaborator or at least sympathetic governments. Others feel that the prosecution of grey-headed, aging old men and women is unnecessary. The sins of youth, the prevailing attitude seems to be, should just be quietly forgotten.

“I think the best way to explain it is to compare a serial killer to a 90-year-old Nazi,” he says passionately, “In other words, if a serial killer were on the loose in Lithuania or Latvia, Estonia or Ukraine, countries which have a terrible record in terms of punishing Nazi war criminals, I can promise you the local police and prosecutors would be doing everything possible to find that person and make sure he’s dealt with in a manner which would prevent him from doing any more harm. What’s the likelihood of a 90-year-old Nazi war criminal killing anybody? Zero. So in other words, these countries understand that all they have to do is wait it out and ignore people like me and the Simon Wiesenthal Centre and they will spare their country the embarrassment, the expense, and the whole mess of it.”

That said, Dr. Zuroff and his colleagues at the Simon Wiesenthal Centre are relentless. When I ask him how many war criminals he has tracked, he has to pause and think about it.

“Well, I would distinguish between the number of people whose escape routes I tracked down to the number of active cases I played some role in bringing in, resulting in legal action taken against them,” he replies thoughtfully, “So was able to find the post-war escape, or track the post-war escape, of about three thousand suspected Nazi war criminals. And I did it by cross-referencing lists of Nazi war criminals that I compiled to records of the international tracing service which was compiled by the Red Cross after the war, in the wake of millions of requests for information on people who had been living in Europe and that you could say, you know, sometimes people have this eureka moment and that really changes their life. So that’s basically what turned me from a researcher into a Nazi-hunter, that discovery.”

Dr. Zuroff has many successes. But when I ask him which unresolved case is the most frustrating for him, he doesn’t have to pause. It’s a fascinating and infuriating story, worth including here in its entirety:

“One case is the case of Albert Heine, a doctor [nick-]named Doctor Death. A notorious sadist, someone who did horrible things to many inmates of the camp – injected oil and gasoline into their hearts to murder them, cut off limbs without anesthesia, tortured people, did horrific, absolutely horrific things and our help was enlisted by the German police which is something that is, actually, relatively rare. Usually there’s a lack of cooperation between NGOs and governmental agencies dealing with prosecution. But in this case our help was enlisted by a special unit of the German police who had been entrusted with trying to find Heine. Because what happened in this case was that Heine was about to be prosecuted in Baden Baden where he lived in ’62, and apparently someone tipped him off and he disappeared. And Heine wasn’t found.

I know it was Simon Wiesenthal who was looking for him and he made sure that we put him on our most wanted list in the ‘80’s, and what happened was in 2004 one of his sons committed a financial crime in Germany and all the bank accounts of the Heine family were investigated. Lo and behold, there’s a bank account in Heine’s name in a bank in Berlin, with 1.2 million cash and eight hundred thousand in bank shares, in shares, in stocks and the money hadn’t been touched in years. And the suspicion then became–well if the money’s still in the account, then obviously the guy’s still alive.

When we launched Operation Last Chance in Germany in 2005, the German police asked us to name Heine as the number one target even though the objective of Operation Last Chance was to find Nazis we didn’t know about, not aces like Heine. We agreed, I mean, we welcomed the opportunity to work with the German police, and we actually had very good cooperation with them and to say that we could help find someone like Heine, that’s a great achievement and we also had one very big advantage in that case, which was that the regular prize that we were offering Operation Last Chance was initially $10, 000 then $25, 000. But in the case of Heine the government was offering 130, 000 Euros. So we were able to double and then to get the Austrians to give another 50 000 because he was an Austrian, born and educated in Austria, and we had a lot of money.

And that could open the mouths of many people who otherwise wouldn’t be speaking to us. We devoted a lot of time to this. I went twice to South America, twice to Chile, twice to Argentina. We and the police, basically we reached the conclusion that Heine was somewhere in Chile or Argentina. And we caught his daughter. He had a daughter, an illegitimate daughter from his mistress, who was living in Chile and she traveled very often. It was a place where Nazis had found shelter after the war. It looked as if all the arrows pointed in this direction and we were hoping, we had hopes of finding the person.

There was even one informant who met Heine’s son-in-law in a certain place in an island opposite Chile. And this guy was coming, the son-in-law was coming out of a supermarket with his hands full of groceries and the informant said to the guy, “What are you doing on the island?” because he had originally lived on the island, the other one had originally lived on the island and he said, “Well, I’m going to visit relatives.”

Well, now this person had worked with the son-in-law. He knew that the son-in-law had no family on the island and all of a sudden everything seemed to come into place. And the person, the son-in-law had a [residence] in a very secluded place. They’re incredibly hard to find, but it turns out that it wasn’t Heine and the [house] had been destroyed by the elements a couple of months previously and what ultimately turned out that several months after this trip the New York Times and German Channel Two revealed that as a result of an interview with one of his sons, who claimed, after saying he hadn’t seen his father for fifty years, that Heine had actually died in Egypt in ’92. And some relatives subsequently gave the police a suitcase full of documents regarding his stay in Egypt on the condition that the Wiesenthal Centre not get the information, but it was obvious that Heine had, at some point, lived in Egypt. The problem was that the son claimed the following in terms of the natural question – if he died in ’92 then where’s the body?

So the son told the following story. In wake of the peace treaty between Israel and Egypt, Heine converted to Islam for fear that Egypt might extradite him to Israel. Obviously, in his mind, converting to Islam was going to protect him in Egypt from being extradited. In any event, before he died, according to the son…one second! After he converted to Islam he was adopted by a Muslim family. Now before he died, he told his son he wanted to donate his body to science. He’s a doctor, after all, so it makes sense on a certain level. But the Muslim family found out about it and in Islam Sharia, it’s against the religious law to have an autopsy or to cut up the body in any sense. You’re supposed to bury it whole. And the Muslim family found out about this and they kidnapped the body, they stole the body, but they couldn’t give him a normal funeral because they had stolen the body. So what did they do, according to the son? Cairo has quite a few mass graves for people who have no resources to have a normal funeral so they threw the body – this is the story anyway – threw the body into a mass grave, supposedly in 1992. Now, go find the body! Impossible! There’s no way on earth you could find it which is a perfect solution for them. In other words, in theory, it gets us off Heine’s track and, in any event, if it is true, prevents us from ever confirming it and in a sense he’s sort of torturing us. And the issue remains unresolved.”

And the time for justice and resolution is rapidly running out; as Nazi war criminals are rapidly dying of old age. This, Dr. Zuroff tells me, is no reason to give up the fight. It’s not too late.

“My message is that justice is obscenely important,” he tells me urgently, “It’s one of the things that we owe the victims because very one of the Nazi victims deserves that an effort be made to find the person, persons, who turned innocent men, women, and children into victims. These are the last people on earth who serve any sympathy because they had absolutely no sympathy for their victims. When you look at these people, and I can promise you, when the time comes for them to go to court either on their own initiative or the advice of attorneys, they’ll make every effort to look as sick, frail, as out of it as possible. So don’t think of them in those terms. Think of them as they were at the height of their physical strength and they devoted all their energies to mass-murdering innocent men, women, and children. That’s why they’re in court today.”

Indeed they are. And as Dr. Efraim Zuroff hangs up the phone, I think of the appalling black and white photographs of aging rabbis and elderly Jewish men and women lining up for the gas chambers, forced to their knees in the snow before gaping mass graves, or standing helplessly in trenches as the Einstatgruppen prepped their machine guns. These men attempted to destroy an entire people. Time cannot erase those crimes. And as Dr. Efraim Zuroff says, it’s never too late for justice.