Blog Post

Guest of the Greatest Minds

By Jonathon Van Maren

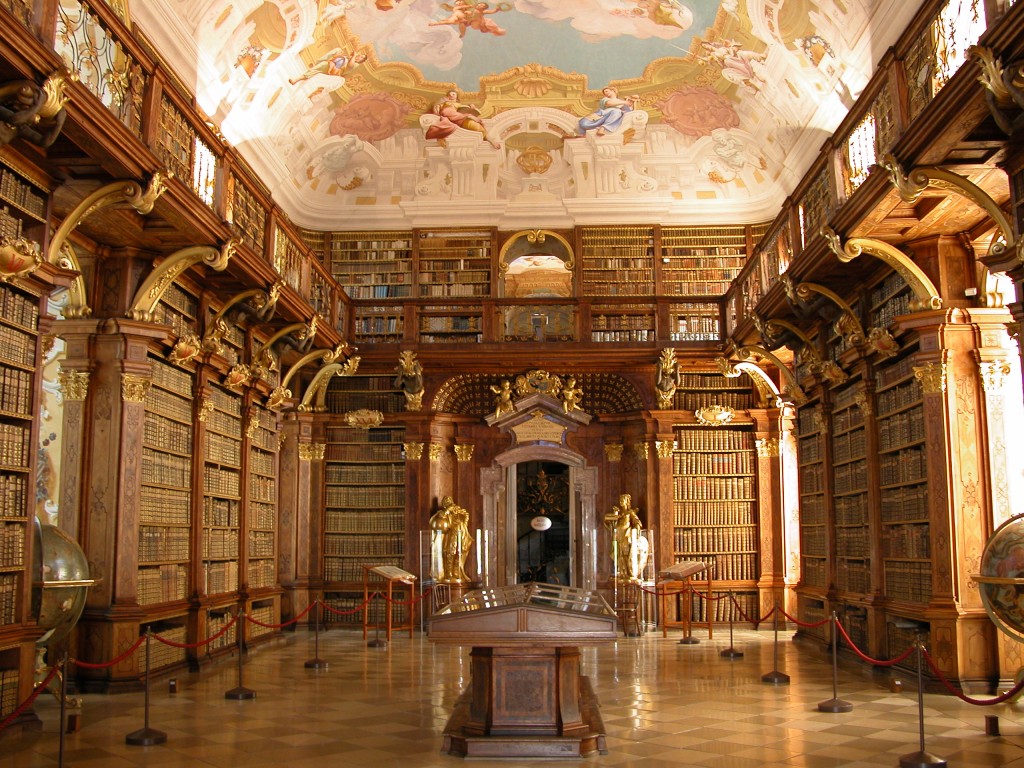

As far back as I can remember, I wanted my own library. Not just a little bookshelf in the corner with my own small collection of volumes, but a big library, a grand library, a place where books and ideas and people and artifacts of all types cluttered about while I surveyed the grandness like a dragon hoarding a cave of literary jewels. Competing smells, perhaps—that “new book smell” colliding with that of old leather. Robin Sloan noted that, “Walking the stacks in a library, dragging your fingers across the spines—it’s hard not to feel the presence of sleeping spirits.” Walking into my own half-complete but slowly growing basement library, I feel the same way.

The big, black bookcases lining my walls hold thousands of volumes—memoirs, philosophies, histories, and sacred texts. American presidents, Greek philosophers, Israelite prophets, and Roman historians share space with political demagogues, bygone revolutionaries and the academics who tried and do try to explain them all. Their incompatible ideas are linked only, perhaps, by their placement on a shelf. Along the top of the bookcases are items I’ve collected during my travels—a brass menorah from Jerusalem, a little painting from Prague, an ammonite fossil from the coolies of Alberta, a card bearing the signatures of Ronald and Nancy Reagan. Because these things make my library complete—little bits of historical flotsam and jetsam, fragments of the past that connect me in a real, physical way to the events described within books that sleep on the shelves like dormant giants.

On the wall, there is a framed copy of the Liberator from 1859, with headlines screaming for war with slavery and war with the slaveholders. The left-hand side announces the editor: W.M. Garrison. There is the TIME Magazine announcing George W. Bush’s victory in 2004—an autographed copy of his campaign autobiography lies on the desk in the corner, where stacks of signed books wait for bookshelves. These signatures give me a little thrill—the men and women who wrote these books held these very volumes in their hand, and wrote their names—some—like Mark Steyn, Newt Gingrich, Senator Jim DeMint, and Khaled Hosseini—to me personally. Others have simply scrawled their names in the front of the book—politicians like Margaret Thatcher and Brian Mulroney, famous writers like Peter and Christopher Hitchens, and cartoonists like Lynn Johnston, who even doodled a few of her famous Canadian characters in the front cover.

Books are still stacked everywhere, because I didn’t realize quite how many things I had accumulated. On the desk, piles of poetry by everyone from Tennyson to Byron to Teasdale sit beneath a record player and stacks of records bearing recordings of everything from JFK’s Inaugural Address to Winston Churchill’s speeches to Johnny Cash, live from Folsom Prison. A few old newspapers, a fraction of the collection I’ve accumulated, lie next to the desk. (My upstairs foyer has become what I like to call “The Hall of the Greatest Generation,” lined with original newspapers describing all of the majors battles of the Second World War. I prefer my hallway to look like Remembrance Day rather than Pottery Barn.) Toppling piles of literary masterpieces and modern fiction are stacked nearby, Tolkien and Tolstoy, Thoene and Twain.

A glass showcase that sits in between a large globe and the desk contains all sorts of historical fragments—a bit of brick from Abraham Lincoln’s house, a bit of concrete from the Berlin Wall, rusty bullets from faraway battlefields. These physical echoes are crowded among campaign pins for Richard Nixon, ancient pottery the Roman Empire, an Egyptian dagger from the time of the Pharaohs, a Nazi helmet dug out of the sand of Omaha Beach, and a trilobite fossil from Noah’s Flood. If you’re quiet, you can imagine it, thinking of the thousands of hands that touched the coins and pottery and weapons, the people who perished and were murdered, the voices that rang out around these silent witnesses. If I’m quiet, my library does not just have things, it has feelings—the books, the artifacts, the little pieces of lives long over pulse with rage, with love, with ideas, with life, with history. Bullets and bombs, Genesis and genocide, pagans and politics, love and war. These things make the silence fairly roar.

My house without a library, I think, would be like a body without a brain. I cannot possibly think of any way to describe this essence better than the poet Josephine Beaty, and thus I will let her do it for me:

“The harvest of the years awaits you here,

Culled with slow toil, and heaped with bloody sweat,

The truths that men have died to bring to light

Are laid before you in these quiet halls.

Upon these shelves your eager hands shall find

The keys to open doors not yet unlocked,

The torch to kindle new and brighter lamps,

The chart to plot your course beyond the stars,

The clues to all the labyrinths of thought.

Here you shall meet the men whose names are carved

Deep-hewn forever on the rocks of time…

You shall be guests of all the greatest minds.”

A library is not just a place. It is an organism, a hodgepodge of humanity. Shelves teeming with ideas, relics, leftovers of civilizations past and present. A house without one is incomplete.