Blog Post

Nietzsche’s Madman

By Jonathon Van Maren

In my debates on a variety of social issues, there is one question that almost no secularist seems capable of answering with any degree of confidence: Where does our morality come from?

One would think that this is an important question to have an answer to. I’ve watched university students struggle to find a moral framework that condemns rape for a reason other than, “I don’t think that should be allowed.” I’ve had other students admit that murder could not be considered “objectively wrong” in their own morally relativistic world view. I’ve seen hundreds of students genuinely stunned to realize that their worldview was completely devoid of anything that could say some actions or behaviors were wrong, other than a feeble appeal to “social contracts” or some unintentional paraphrasing of the Golden Rule dressed up as social Darwinism.

Our civilization has not yet come to terms with the fact that once the Judeo-Christian system of morality has been thoroughly destroyed, we will have nothing to replace it with except the leviathan of the state. Without the Christian code of conduct that sustained and ordered society for so long, it will fall to the governments to christen themselves as the final authority on what is right and what is wrong, what is love and what is hate, and what is acceptable and what is not. And yet, most people do not seem to have considered the implications of this very thoroughly.

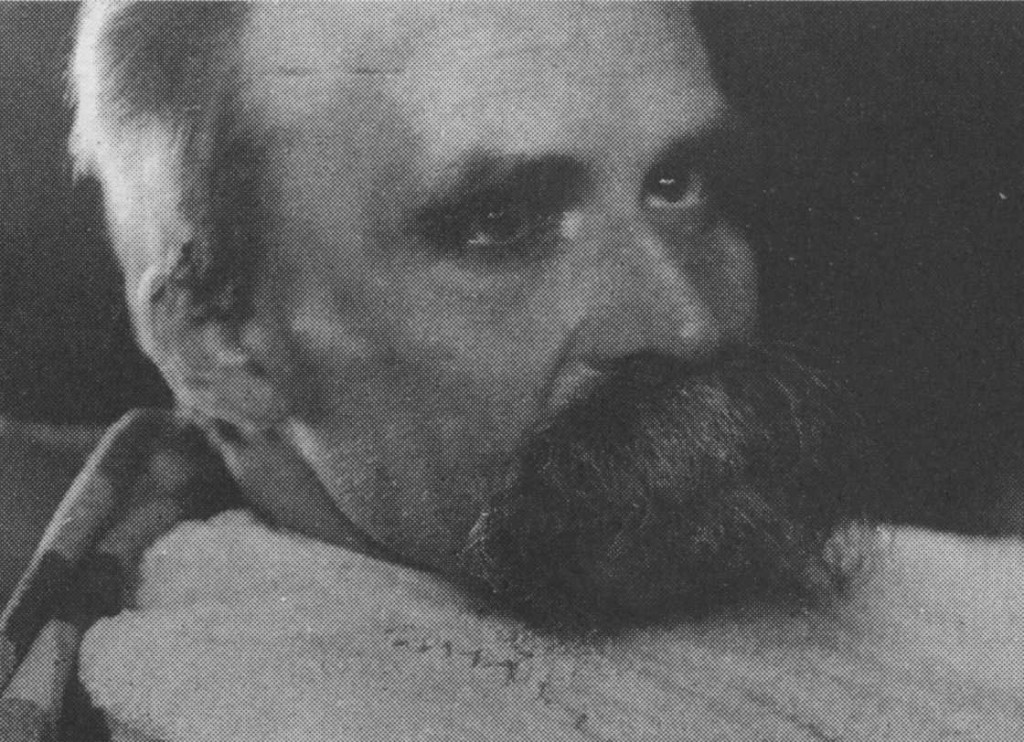

As a university student, I met many freshmen philosophers who loved to sprinkle their self-absorbed atheist soliloquies and strutting moral relativism with quotations from the German writer Friedrich Nietzsche, who famously declared that “God is dead.” Most, it seems, did not dig deep enough to realize that Nietzsche’s pronouncement actually came from a tortured parable called “The Madman,” where he demanded to know, in frantic panic, where morality could come from once God was done away with.

“Have you not heard of that madman who lit a lantern in the bright morning hours, ran to the market place,” he asked plaintively, “and cried incessantly: ‘I seek God! I seek God!’ — As many of those who did not believe in God were standing around just then, he provoked much laughter. Has he got lost? asked one. Did he lose his way like a child? asked another. Or is he hiding? Is he afraid of us? Has he gone on a voyage? emigrated? — Thus they yelled and laughed.”

The madman jumped into their midst and pierced them with his eyes. “Whither is God?” he cried; “I will tell you. We have killed him — you and I. All of us are his murderers. But how did we do this? How could we drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving? Away from all suns? Are we not plunging continually? Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? Is there still any up or down? Are we not straying, as through an infinite nothing? Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder? Is not night continually closing in on us? Do we not need to light lanterns in the morning? Do we hear nothing as yet of the noise of the gravediggers who are burying God? Do we smell nothing as yet of the divine decomposition? Gods, too, decompose. God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.

“How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it? There has never been a greater deed; and whoever is born after us — for the sake of this deed he will belong to a higher history than all history hitherto.”

Here the madman fell silent and looked again at his listeners; and they, too, were silent and stared at him in astonishment. At last he threw his lantern on the ground, and it broke into pieces and went out. “I have come too early,” he said then; “my time is not yet. This tremendous event is still on its way, still wandering; it has not yet reached the ears of men. Lightning and thunder require time; the light of the stars requires time; deeds, though done, still require time to be seen and heard. This deed is still more distant from them than most distant stars — and yet they have done it themselves.”

Nietzsche understood what many of his modern followers do not: That the decomposition of morality was a mortal threat to society. He realized that to deny God’s existence, even if one truly believed He did not exist, was also to deny the existence of the morality that held civilization together. Nietzsche knew, before he went mad, that Christianity stood between man and meaninglessness, and gave human life inherent value. He died in 1900, before he could see Germany descend into the black abyss of murder and war that illustrated, in bloody crimson hues, what could happen when the state replaced God as the ultimate authority.

Today, Christians try to point out that we in the West are doing what has been done before. We are killing human beings on both ends of life’s spectrum, and calling it good and merciful. We are extracting, piece by jagged piece, each and every part of our Christian heritage from the national stage. Indeed, much of what Christians believe is now considered to be wicked and hateful. And again, the state will fill the void as the final arbiters of what is right and what is wrong. If history tells us anything, it is that the state is a fickle and dangerous master.

Nietzsche’s story of the atheists in the marketplace mocking the madman in search of God reminded me of another, more ancient story. I wonder if Nietzsche actually had this story in mind when he had his laughing heathens ask the desperate man if perhaps God was on vacation, or hiding. The great Israelite prophet Elijah did the same, after challenging the priests of Baal to call upon their god for an answer. As the priests cried out and danced and slashed themselves with knives, Elijah began to mock their efforts:

And it came to pass at noon, that Elijah mocked them, and said, Cry aloud: for he is a god; either he is talking, or he is pursuing, or he is in a journey, or peradventure he sleepeth, and must be awaked.

When the pagan god Baal did not answer his priests as the breathless people watched, Elijah stepped up to the altar.

36 And it came to pass at the time of the offering of the evening sacrifice, that Elijah the prophet came near, and said, Lord God of Abraham, Isaac, and of Israel, let it be known this day that thou art God in Israel, and that I am thy servant, and that I have done all these things at thy word.

37 Hear me, O Lord, hear me, that this people may know that thou art the Lord God, and that thou hast turned their heart back again.

38 Then the fire of the Lord fell, and consumed the burnt sacrifice, and the wood, and the stones, and the dust, and licked up the water that was in the trench.

39 And when all the people saw it, they fell on their faces: and they said, The Lord, he is the God; the Lord, he is the God. (1 Kings 18)

A reminder that history tells the same story, over and over again: Societies reject God, and instead serve kings and governments and idols. And over and over again, that story ends abysmally. Our society does not appear to understand that just yet. As Nietzsche’s madman noted, perhaps it is too early for people to listen to such warnings. Perhaps the worst impact of removing God is yet to come. We will find out together.

But we have no reason to believe that our story will end differently than so many others. In the words of Lord Byron:

There is the moral of all human tales;

‘Tis but the same rehearsal of the past,

First freedom, then glory—when that fails,

Wealth, vice, corruption—barbarism at last,

And history, with all her volumes vast,

Hath but one page.

Well said, Jonathon.

I think there is a lot of truth to the idea that our civilization has been functioning on “borrowed capital,” the residual moral and ethical strength of a largely Biblical worldview (or at least Biblical assumptions about morality and ethics). But like you said, there are not many liberals and atheists who really see where this whole thing is headed… these are heady days for them – the fulfillment of their dreams – and the excitement of it all keeps them seeing that the foundations they’re so gleefully dismantling have been supporting the whole building.

I once had a discussion with a group of pro-life agnostics and atheists online where I posed the basis for fundamental moral issues on general consensus morality, namely, fundamental rights and freedoms being based on what the vast majority of people know naturally to be right or wrong. (ie. murder, torture…) It seemed a sturdy edifice at first, then my fellow debaters realised that if what was wrong meant what naturally makes the majority of humanity uncomfortable, then, well, that has to change our currently popular narrative on homosexuality. The conversation kind of petered out from there.