Blog Post

In Europe, a “pro-life revolution” is brewing

By Jonathon Van Maren

I met 26-year-old Manuela Steiner at the Casa Antonio Pizzeria in the Erzabt-Klotz-Straße 9, a stone’s throw away from Salzburg University. It was a beautiful day. A handful of stylishly-dressed men and women stood at a waist-high table sipping white wine and students were devouring their large pizza slices on flimsy tables on the cobblestones in front of the large plate-glass window, eyes fixed to their homework. There was a faint breeze, a few birds could be heard, and the white walls of the Hohensalzburg Fortress, perched high above the city, gleamed in the spring sun. The fortress is a reassuring sort of presence, having cast its benevolent shadows on the city below since 1077. The residents are pleased to inform visitors that it is the only fortress in Europe never to have been conquered—not during the German Peasants’ War in 1525, nor during the Thirty Years’ War a century later.

Manuela works for the Austrian pro-life organization Youth for Life, which was formed in 1989 after Dr. Bernard Nathanson’s horrifying film The Silent Scream came to Europe. Abortion had come to Austria on January 1, 1975, and can be performed up to twelve weeks on demand and up until birth for the vaguely defined “health of the mother” or if the child has an “incurable problem.” (Today, a quarter of pregnancies in Austria end in abortion.) In response, pro-life Austrians organized silent marches in Linz, Salzburg, and Vienna. I have attended one silent march in Europe, and the symbolism is a powerful reminder of the murdered voiceless. Originally, Manuela told me, the Austrian pro-lifers thought that abortion would end in short order. They soon realized that they would have to escalate their activism, and these marches became a symbol of defiance, a reminder to their fellow citizens that not all Austrians had bowed to the Culture of Death.

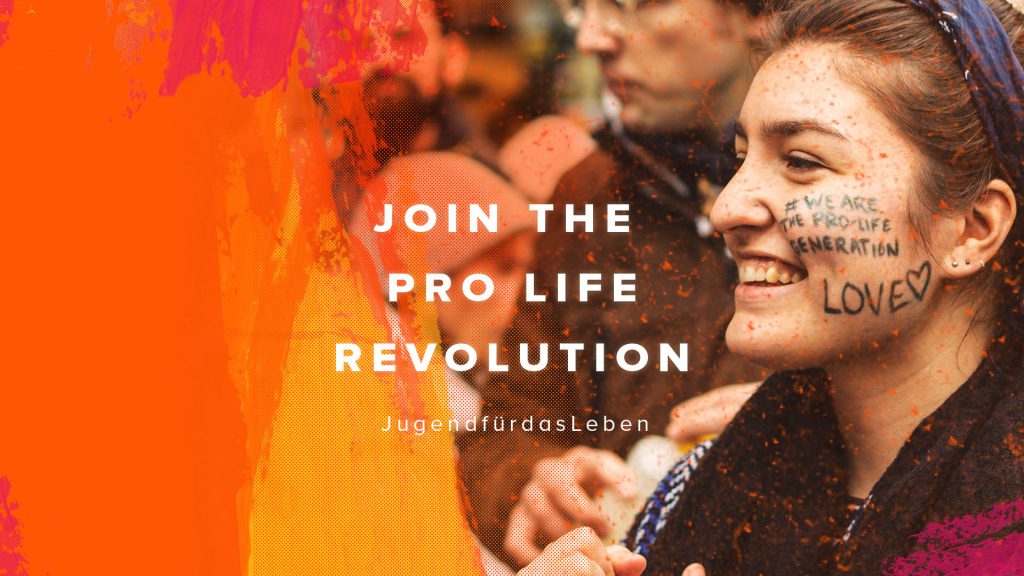

In addition to the march, Youth for Life began an annual pro-life tour to raise awareness about abortion, giving media interviews and presentations, distributing fliers, and doing outreach with pro-life info tables along the way. The media often covered these efforts, pushing pro-life talking points into the European press. Last year, there were a 140 participants, and they are hoping for more this year with an International Pro-Life Tour for a Europe without Abortion under the motto “Making Abortion History” leaving from Bavarian Augsburg on July 27 and trekking through Innsbruck to their final destination in Bolzano, Italy. Manuela will be organizing this year’s march through three countries in three weeks, and up to hundred adults and teenagers are expected. It is not an easy hike, Steiner admits, but “we cannot just sit at home, knowing that every year many children are aborted.”

Youth for Life’s most effective work has been gaining access to schools, where they give two-hour presentations on the reality of abortion in religion and biology classes. Speakers explain the science of when life begins, the abortion laws in Austria, potential complications resulting from abortion, and show the students how abortion procedures work. When students see how tiny pre-born children are poisoned, pulverized, and pulled from womb, Steiner says, they are nearly always dead silent, watching in shock. Most people do not know how horrifying abortion is. Most are horrified when these facts are revealed. Surveys taken after the presentations indicate that 80% of students have some shift in their opinion, and 60% become opposed to abortion. This is the crux of what Youth for Life does: Young people speaking to other young people about what abortion does to the youngest people.

In addition to working for Youth for Life, a new organization was launched on March 24 out of Linz with Manuela as the president: ProLife Europe, an initiative to equip, train, and activate student groups across the continent. In contrast with Canada and the United States, where pro-life campus groups are common, most European campuses have no active pro-life club. ProLife Europe aims to change that, starting with three groups in Germany and nine in Austria and three active coordinators. In addition to a German coordinator and Manuela working as both president and the Austrian representative, Bethany Janzen, an American from Oregon who originally worked with Students for Life of America, has joined the team as an international coordinator. As Manuela and I walked across the campus of the University of Salzburg, with Manuela sitting down next to students enjoying the sunny day outdoors to hand them pro-life literature and ask them if they would be interested in joining a pro-life group, Bethany was connecting with students in Denmark. (When I asked a Danish journalist if there were any active pro-life groups in her country last year, she told me there were none that she knew of.) It is an uphill battle, but the girls of ProLife Europe are in possession of fierce determination and enthusiasm.

There are difficulties, of course. One major Austrian initiative has been a petition for Fairändern, which means, roughly translated, “Fair Change.” Pro-lifers demanded that the government offer more counselling, publish official abortion statistics, and provide better support for people with disabilities, among other policy changes. The Austrian government has not yet replied to the petition, and is instead soliciting a response from the devoutly pro-abortion Amnesty International and International Planned Parenthood, which is rather like asking a wolf to offer his opinion on veganism. One of the greatest difficulties facing pro-lifers in Austria and Germany, Manuela tells me, is that nearly everyone agrees that the pre-born are human, but most simply believe that the mother should still be able to choose whether that human lives or dies. In addition, the same eugenic mindset that has crept into other countries—I found this while doing presentations in the Netherlands—is present here, as well.

All that said, the coordinators of ProLife Europe are willing to do the heavy lifting it takes to get a student movement started, even if it means talking to students one at a time. Different regions come with different challenges—Manuela noted that Eastern Germany still has more entrenched views on abortion due to their decades-long experience under Communist rule—but steps are being taken to make the pro-life worldview accessible to all. Austria’s Youth for Life, for example, is an explicitly Catholic organization, while ProLife Europe is secular, hoping to attract those who respect fundamental human rights from all walks of life. The work has only just begun, but with less than a month of work under their belts, connections between pro-life groups already criss-cross the continent and the infrastructure of resistance is slowly coming into place.

After a long and productive conversation about pro-life strategy and swapping ideas and insights with Manuela, I walked back towards my hotel to find a place to work on my laptop. The blossoms were out, and they made the breeze fragrant as I headed through the streets and squares. Beautiful music was straining from windows high above the twisty, cobble-stoned alleys as musicians began practicing for the Mozart concerts that happen every night in Salzburg to celebrate the life of her most famous son. Nearby is St. Peter’s Abbey, founded in 696 by St. Rupert, which hosts the oldest restaurant in Europe—Charlemagne himself once ate there. Sleeping in the cemetery are Martin Luther’s close friend Johann von Staupitz, Johann Hadyn, and Maria Mozart. The oldest graves are from 1288 and 1300; the newest are from this decade. It is the perfect picture of today’s Europe: The ancient jostling for space with the modern.

Everywhere in Salzburg, there are unexpected reminders of the uglier elements of Austria’s past. Looking down at the sidewalk as I waited to cross the street, for example, I found that three golden plaques were embedded into the asphalt, each bearing the name of someone who had been murdered: 72-year-old Irma Her, deported to Theresienstadt July 30, 1942, dead less than four months later; 70-year-old Anna Stuchly, deported to the same camp on July 14, 1942 before perishing in Treblinka; Josef Witternig, an Austrian politician, who died in Salzburg on February 28, 1937. A nearby sign informed us that it was only a short thirty-minute drive to Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest, which is nestled in the Alpine peaks above the city—the men of Easy Company, which took Berchtesgaden in 1945, enjoyed the gorgeous view with drinks looted from the fine collection of the Nazi elites. And it is the story of an Austrian’s resistance to the Nazi invasion, the tale of the Von Trapp family singers that was immortalized in the 1965 musical The Sound of Music, that draws tens of thousands of tourists here each year.

Just before leaving Salzburg, I heard a story that I’d never come across before. The eldest Von Trapp daughter, Agathe, had apparently related how her parents made the decision to flee the country, after being warned that Georg Von Trapp’s refusal to join the Nazi fleet had landed the family on an very unpleasant list. Warned by a family friend who had joined the Nazi Party, the Von Trapps realized they needed to leave, but Maria Von Trapp wanted “divine approval concerning the move.” As Agathe recalled it, “Papá called us all together, opened the Bible, and let his finger pick a passage at random. Then he read it to us: ‘Now the Lord had said unto Abram: Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father’s house, unto a land that I will show thee.’” The decision was made, and the family departed (although in much less dramatic fashion than portrayed in the film.)

The story reminded me that at all times and in all places, good and evil are fighting for supremacy. In each era there are great evils, and in each era there are those who choose to resist. Sometimes those evils explode onto the scene accompanied by war and holocaust, and other times they slither into national consciousness disguised by the soothing rhetoric of personal choice and individual liberty. Sometimes the ugliness is apparent and the brutality is loud and jarring, and other times tiny lives are snuffed out silently and disposed of while people sip their cold drinks on sun-swept verandas and carry on with their lives while others end so swiftly their presence is almost an unheard whisper. The activists of ProLife Europe have made their choice and taken a stand. I hope others will follow their example.

Very cool article. Hats off to Manuela and her crew. It’s a tragedy how Amnesty International, who feign to care about human rights, actually diminish society’s capacity to truly care about one another by promoting the slaughtering of our society’s tiniest, most vulnerable members, the unborn. Simultaneously, the promotion of abortion does the opposite of empowering women as it encourages them to believe in being unable to cope with non ideal situations, coxing them into false security, into a horrific industry that destroys their children. Fair play to all those who strive for truth and justice in getting the word out about what the abortion industry is really all about, about the actual essence of what’s going on within this thing that is intrinsically violent and absolutely destructive.

Thank you for adding this. Its probably a much more uphill struggle than you might ever imagine. I often come across people who are so deeply married to individual autonomy that they are completely blind to the same eventual autonomy of the developing human. They have actually ceased to think, I think.

Anyway, I’m not giving up.

Awesome how can we help ?

Every life matters.