Blog Post

Michael Brendan Dougherty’s memoir shows the path forward in a broken culture

By Jonathon Van Maren

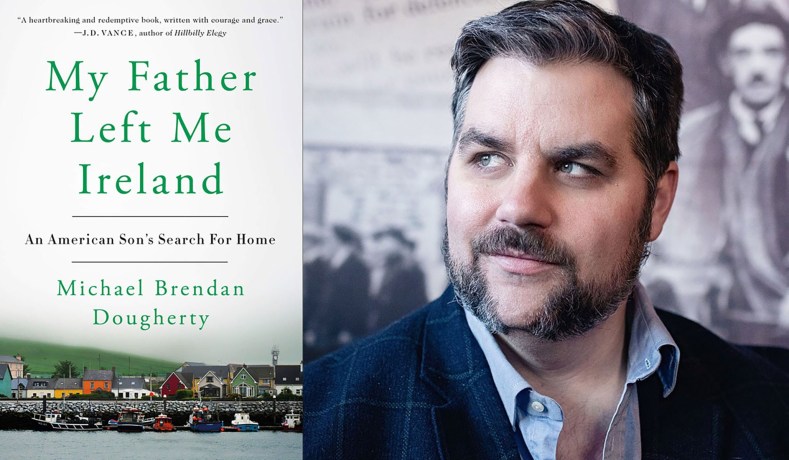

Michael Brendan Dougherty’s mauling memoir My Father Left Me Ireland: An American Son’s Search for Home is the sort of book that keeps coming back to you long after you’ve put it down. Insights that he stuffs into descriptive paragraphs that go unnoticed on first reading suddenly come back to you later on, and you will scurry back to re-read and wonder how in the world you’d missed that.

Dougherty’s story, which traces his upbringing by his Irish-American mother in the United States while his Irish father raised a separate family across the ocean in Ireland, will leave you bruised. He was conceived as the result of a love affair between his mother and his Irish father while she was travelling in Europe, and his father decided to stay in Ireland, visiting his son only when time and money would permit. Dougherty’s descriptions of a son’s longing for his absent father reminded me once again of what genuine privilege looks like in this broken culture: An intact family with a mother and father.

He writes movingly of what his mother sacrificed to raise him on her own. She faced unuttered criticisms contained in the looks she received from those around her, people who wondered why she hadn’t been able to “hang on” to the father of her child. A widow, Dougherty observes, would have received sympathy and a helping hand. A single mother, regardless of her circumstances, was the recipient of veiled judgement. This is something I had not considered before, and something the pro-life movement must keep in mind as it seeks to rebuild a culture of life in the rubble left by the sexual revolution.

Dougherty’s description of his conviction that he’d ruined his mother’s life, that her choice to keep him and raise him had probably prevented her from achieving her own happiness and perhaps even marrying one day, is simply heartbreaking. Dougherty has described his book as a romance between “an American son and his absent Irish father,” but it is impossible not to read this story as a towering monument to the sacrificial love of mothers, without whom we are utterly lost. Dougherty writes much of the conscious sacrifices made by the patriots of Ireland’s 1916 Easter Rising, but it is the instinctual and unspeakably beautiful sacrifice of his mother that shines from every page.

This book is raw and unyielding, and Dougherty allows himself no self-delusions. He ruthlessly dissects his own mistakes, and I shuddered a little with recognition when he noted that as a younger man, he’d been far more interested in wit than wisdom, and that this drive had made him shallow. This sort of self-awareness is painful at any time: to put the resulting discoveries in a book is the sort of ego-piercing that few are manly enough to attempt. Perhaps it is only possible after the source of that shallowness is identified, as Dougherty does on page 180:

I can’t speak for everyone, but I can say with some assurance that mass media was my primary teacher growing up. And it taught me and my friends how to conform with one another. It slipped under the table to me a lesson that sincerity is a kind of weakness. That it will be used against me. And that any sentiment at all, anything that could expose you to the danger of ridicule or the genuine possession of an emotion, should be double- and triple-Saran-wrapped in irony. I suppose we do this for safety somehow, as if unwrapped passion itself is so flammable, it would consume our little worlds at the instant we exposed it to open air.

That is precisely it. Our generation, those who grew up with Family Guy and Jon Stewart and the conviction that all conviction is a joke and that nothing is sacred and that antiquated notions of love, dignity, loyalty, courage, and sacrifice are punchlines in TV sitcoms delivered by celebrities who will be called brave for coming out as a gay—we are terrified of the very things we need to give our lives meaning. We have been told by the iconoclasts that anyone who expresses admiration for these things is a huckster, which has ironically made us an easier target for hucksters because our longings can be exploited by self-interested politicians who can use nostalgia as a tool of resentment. We don’t know who, precisely, robbed us of all of these things, and thus many are willing to listen to those who claim to have a convenient answer to that question.

Dougherty’s memoir particularly resonated with me because it discusses the urge he had to reconnect with his roots after his daughter was born, partially in preparation for the question that was sure to come: Who am I? I had an identical feeling when my daughter was born, and on a recent trip to the Netherlands I had the beautiful experience of watching her play on the cobblestones where her great-grandfather (now 97 years old) played as a boy. She was born in North America because her great-grandparents left a country devastated by the Second World War and the North Sea Flood for a new start, and now their descendants faithfully trickle back to the little villages where they grew up. Many of us feel a sense of familiarity with these places even if we are visiting them for the first time, a pull that defies all logic. That is not because these emotions are unreasonable, it is because they somehow transcend reason.

For Dougherty, who was writing this book around the time when the centennial celebrations were being held, this rediscovery of his roots drew him to study the Easter Rising. The stories of those men and their short revolution prompted him to this observation:

And what is says to me now is that the past reproaches the present on behalf of the future. I mean this almost superliterally: The ghosts of a nation reproach the living on behalf of posterity. A nation or a society is not merely a contract between the living, the unborn, and the dead; it is a spiritual ecology that exists among them. A nation exists in the things that a father gives to his children, or else he is shamed before his father and grandfather, and his descendants too. The things that are needed for the future.

This, too, cuts to the heart of things. It is the selflessness of those who threw their lives away for future generations—and love them or hate them, you must grant them that—that gets snorted at by the revisionists precisely because it is so counter-cultural. More than that, it makes them nervous, because many of them are forced to admit not just that they wouldn’t do such a thing, but that they cannot understand holding the sort of loyalties that would prompt the consideration of such sacrifice. Thus the revisionists have to undermine the heroes, puncture the stories with accusations of strategic stupidity, and then satisfy themselves with the conclusion that their actions were madness. This the revolutionaries of the Rising may have granted—but it was, as one said, “a glorious madness.”

But civilization is only ever produced by sacrifice: Parents for children, children for parents, the community for the nation. Once we discard that concept, we have eliminated our survival instinct. As Hilaire Belloc put it, the “barbarian” wants to “consume what civilization has slowly produced over generations of selection and effort,” but has no “comprehension of the virtue that has brought them into being. Discipline seems to him irrational, on which account he is ever marvelling that civilization should have offended him with priests and soldiers…We sit by and watch the barbarian. We tolerate him in the long stretches of peace, we are not afraid. We are tickled by his irreverence; his comic inversion of our old certitudes and our fixed creed refreshes us; we laugh. But as we laugh we are watched by large and awful faces from beyond, and on these faces there are no smiles.”

It is this warning that Dougherty issues to his readers, noting that the cultures and nations that have nurtured and nourish everything we love may be slipping away from us: “We have, perhaps fatally, polluted this ecology. We have reversed the process in which humility before the past leads to self-sacrifice in the present and new life and regeneration for the future. We have declared this state of things the end of history, imagining that people can live as consumers only, bored with life.” His memoir is a clarion call to seek things of true meaning, and to reject cardboard consumer culture in favour of the inheritance we have been denied by the elites who insisted we had no need for such things anymore.

It is Dougherty’s own story that provides the hope. As he held his infant daughter and gazed at her beautiful, innocent face, he saw the scattered pieces of his broken family made whole again in the form of a child who symbolized a rising generation and a fresh start. Children are a blessing, not a burden, and they bring the promise of new beginnings—and continuity with old ones. The children of the sexual revolution can provide their own offspring with the very things their hearts longed for, and the very things they were denied. A father, a mother, and children: A tribe to rise up against a culture of barbarians who have wreaked a half-century of destruction on a civilization built by families.