Blog Post

Walking where William of Orange lived and died

By Jonathon Van Maren

At the bottom of the staircase at the Prinsenhof, there are still two jagged holes where bullets knocked chunks out of the wall, the only damage to an otherwise smooth white surface. They are covered by a glass pane, and my wife and I squinted closely at it—it is on this precise spot where, 435 years ago on July 10, 1584, a fanatical Catholic assassin named Balthasar Gerard stepped out from behind a pillar as William of Orange left the dining room and began to climb the staircase just behind his wife, sister and daughters. Gerard, who had gained an audience by posing as the beleaguered relative of a martyred Calvinist, was wielding two wheel-lock pistols, and he fired directly into William’s chest at point-blank range. The 51-year-old prince slumped onto the stairs. Some historians believe that the force of the bullets would have killed him instantly, while others say his final words were for the people he led: “My God, have pity on my soul; my God, have pity on this poor people.” Several accounts say that his sister Catherine, who reached her fallen brother first, asked him urgently: “Do you die reconciled with your saviour, Jesus Christ?” As the blood drained from his face and he turned as gray as ash, he whispered a single word: “Yes.”

The 27-year-old Balthasar Gerard had come to the Prinsenhof in the Dutch city of Delft to murder the Silent Prince in exchange for a staggering reward of 25,000 crowns offered by the King Phillip II of Spain, persecutor of the Dutch Protestants and erstwhile Lord of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands. Gerard would never receive the reward, as he was captured and imprisoned before he could escape the city. He was subjected to the cruel wrath of a mourning people, tortured horribly in prison for several days, and then publicly executed. His right hand, the one that had fired the fatal shot, was roasted with a red-hot iron, he was flayed in several places with pincers, and, according to a macabre display at the Prinsenhof, “they cut open his belly and removed his intestines” before throwing “his heart in his face.” He said not to have made a sound throughout all of this, and such scenes of savagery were hard to conjure as we walked past the site of his death at the Markt, with the famous fish stalls, the outdoor restaurants, and the brazen pigeons lying in wait to steal falling food. Gerard’s family received several estates in exchange for their assassin son’s deeds from a grateful Phillip.

Delft is one of the most beautiful cities in the Netherlands, a cityscape of brick and towers and cobblestones, ancient churches and glorious canals. Historians place its genesis somewhere around the 11th century as a landlord court, and from a medieval village it developed into a small city, receiving its charter in 1246. William of Orange took up residence in Delft in 1572, the leader of the exploding Dutch resistance against the cruel Spanish occupation known to history as the Eighty Years’ War. It served as an ideal place for the Dutch freedom fighters to headquarter, equipped as it was with strong city walls (only one of the impressive gates still survives today) that assisted in repelling a Spanish attack in October of that year. When the Dutch declared independence from Spain with Act of Abjuration in 1581, Delft became both the de facto capital of the fledgling confederation as well as the formal seat of the House of Orange. Ironically, the murder of the Silent Prince actually backfired for Phillip, transforming a mortal leader into a martyr and a symbol of Dutch independence, and some historians speculate that he ended up posing a greater threat to Spanish rule dead than alive.

Inside the Prinsenhof, it feels as if the long-departed members of the House of Orange still live and might be just around the corner. The museum has created an almost eerie atmosphere in places: Shadows of the children who once played in the rooms and ran laughing down the hallways flit about the walls, and at one point my little daughter Charlotte chased after a small girl in a bonnet, a ghost of centuries before. She also scurried about in William of Orange’s bedroom, just as his own children might have done—although William liked to have the windows open, and the museum officials now have them latched tightly shut. A plaque affixed to the wall just inside the room informed us that it was in this room, which doubled as his study, that William “would receive his most important counsellors…and probably discussed his Apology, his written response to Phillip II putting a price on his head…His private room is now once again receiving the attention it deserves as a place of commemoration.” A display case containing one contemporary edition of the Apology helpfully explained with a Trumpian twist that not everything in it was completely accurate: “With a clever propaganda strategy, William managed to win the Netherlands to the rebels’ cause. He first targeted the Duke of Alba. Next he turned on King Phillip II. In the Apology, he lashes out ferociously. Phillip II is cruel and is even believed to have murdered his wife. Some passages would now be considered to be fake news. The Apology was translated into five languages, sent to all royal houses and became a bestseller throughout Europe.”

Charlotte was especially fascinated by the portraits of the solemn, chubby children of the House of Orange, who regarded her with a dignified air that belied their age. Incidentally, William’s third wife was also named Charlotte—she was a former French nun who bore him six daughters and loved him dearly, apparently dying of exhaustion while nursing her husband back to health after an assassination attempt in 1582. When William heard the news, some feared that the grief might kill him. He was married again the following year on April 12, 1583 to the widow Louise de Coligny, the daughter of the French Huguenot leader Gaspard de Coligny, who had been murdered just over a decade before during the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in Paris. One riveting painting in the Prinsenhof shows Louise clad in mourning black, tears running down her cheeks, clutching their sleeping infant son Frederick Henry with a portrait of her murdered husband propped up on a pillow beside her. Frederick Henry, born only a few months before his father’s assassination, would become the grandfather of William III, king of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

The Prinsenhof is a place of light and shadows, with one projected silhouette in the church sanctuary triggering the reminder that it was here, on October 3, 1574, that William finally heard that his plan for the Relief of Leiden—the breaching of the dykes—had been successful. William gave more than his own life in the battle for Dutch independence. Of his four brothers, three died in battle: Adolf at the Battle of Heiligerlee on May 23, 1568, which rendered the first Dutch triumph a personal tragedy for William, and Louis and Henry at the Battle of Mookerheyde on April 14, 1574, although the family did not know for certain for some time that the brothers had been killed, as the bodies were never found and only absence remained. All three brothers died childless. William was very close to his four brothers, but lost three of them in the war for the Netherlands before dying violently himself. Only one brother, Count John VI, died a natural death in 1606 after attaining the prestigious position of Stadholder of Gelderland.

In death and over time, William the Silent has eventually become a unifying figure. At one of my speaking events later that week, I asked a Catholic pro-life activist how he felt singing the Dutch national anthem. Wilhelmus, which originates from as far back as 1572, is sung from the perspective of William of Orange, glorifying the Dutch revolt against the Catholic king of Spain as a battle between David and the wicked King Saul. In response, it was the Silent Prince that he pointed to. William of Orange had no desire to persecute the Catholics, he noted, and even condemned any mistreatment of them by over-zealous allies like the naval Sea Beggars. The Dutch can lay claim to having invented religious liberty, and William himself led the way by proclaiming that it was impossible to govern a man’s conscience. From that perspective, my fellow pro-life activist told me, the success of William’s war was a victory for all those who prize religious freedom. That, of course, was impossible for me to disagree with.

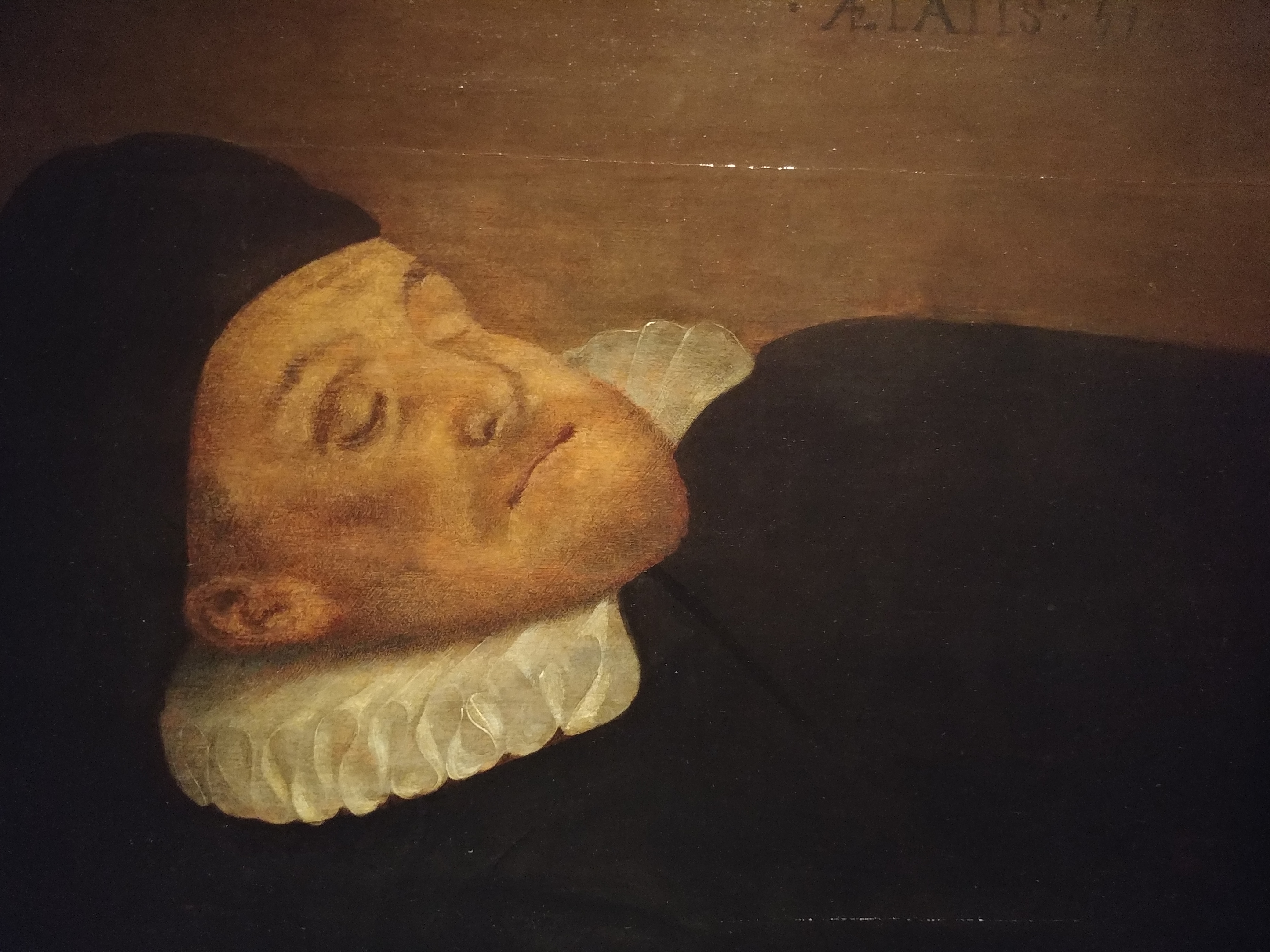

William of Orange is buried nearby in the Nieuwe Kerk, and his tomb features the sculpted prince lying in state atop a coffin with his little dog Pompey, who once purportedly saved his master from a prior assassination attempt by barking and finally pawing at his sleeping face until he awoke, slumbering at his feet. The royal crypt directly below William of Orange’s mausoleum contains the remains of ten of his closest relatives, along with three small coffins that are simply marked as “unidentified.” Two of the three are thought to contain the bodies of the Silent Prince’s stillborn grandchildren, but nobody knows for sure. Originally, the States of Holland forbade all portraits of the dead prince, but the artist Christiaan van Bieselingen was able to take a sketch and turn it into a painting later. It can be seen in the Prinsenhof, the regal bearded face pale but not quite as white as the frilled color, a black hat pressed firmly down on his head. The Father of the Fatherland gave his life fighting for the Netherlands, but tens of thousands still traipse faithfully to pay him homage four centuries later, Dutchmen jostling in the halls of his final home with Chinese tourists who peer closely at the portraits of the men, women, and children of the House of Orange.

On August 3, 1584, the entire city of Delft took silently to the streets to view the funeral procession of William of Orange. Traditionally, members of the Nassau family had been buried in Breda, but this was still wartime and the graves of William’s ancestors were still in Spanish territory. It was a royal event in every way, modeled after the 1558 Brussels funeral of Emperor Charles V. The Dutch wanted it to be clear: This was a statesman of enormous significance, and he would be honoured as such. The bier bearing William’s casket was borne by twelve noblemen, and his second son, Maurice, followed behind. His first son, Philip William, could not take his rightful place as the eldest, as he was yet being held hostage in Spain. The funeral sermon was delivered by Arent Corneille, and the text was from the Revelation of St. John, words that are as true today as they were four hundred years ago: “Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord from henceforth. Yea, saith the Spirit, that they may rest from their labors; and their works do follow them.”

Great blog. Pity history is no longer valued so we repeat it