Historical Essays

How the Great War transformed Western civilization–and is still with us today

By Jonathon Van Maren

My introduction to this series on the 20th century, “The Century that Changed Everything,” can be found here. Part I, “The World Before the War,” can be found here. This is the third installment in the series.

On February 4, 2012, the last living veteran of the Great War died at the age of 110. Florence Green, a British citizen who had served in the Allied armed forces, died only nine months after Claude Choules, the last surviving combat veteran of the war, who also passed on at the age of 110. And with that, the last men and women who could speak from memory of that clash of civilizations that forever changed our world were gone, leaving us to our history books and revisionist squabbles. We have been collectively debating the impact of the Great War ever since.

I never had the opportunity to speak with an eyewitness of World War I, although I saw a few ancient men carefully swaddled in blankets being pushed respectfully to the cenotaph in wheelchairs at some of the first Remembrance Day ceremonies I attended as a boy. To hear the memories of those men and women today, one can only speak with someone who did know them when they were with us, and for that I called Sir Hew Strachan, a British military historian and the author of over a dozen books. Currently the Professor of International Relations at the University of St. Andrews, he is also a council member of the Royal Company of Archers, the Queen’s Bodyguard for Scotland. Before moving to St. Andrews, Strachan was the Chichele Professor of the History of War at All Souls College, Oxford.

“There are [several] veterans who have stuck in my mind,” he told me. “One, predictably, was my grandfather. He didn’t talk about it, yet he gave me boxes of toy soldiers when I was a small boy. His brother was killed, and he was seriously wounded. One of the last things he did was tell my mother—that is to say, his daughter-in-law—to burn the kilt he’d been wearing when he’d been wounded. She said: Hew would like it. He said: Chuck it on the fire. He didn’t talk about it. The first person who really talked about it with me was an art master who’d been in the Royal Artillery during the First World War, a forward observation officer [who] then joined the Royal Flying Corps in 1917. He said to me: I really enjoyed the war. I thought when he told me that—this was at the time of the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War in 1964—he’s obviously an old man now, it’s just him looking back on his youth with that fondness of remembrance. [But] after he died [and] his letters to home were published, [it turned out] he wrote to his parents saying that in 1915 and 1916: Whatever the trials and tribulations, this is the most wonderful enterprise to be part of. So it wasn’t just an old man’s fancy.”

***

The basic facts of how the Great War unfolded are well-known. After the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie in Sarajevo by a Serbian terrorist, Austria-Hungary spotted the opportunity to flex her muscles and declared war on Serbia on July 28, 1914. The small conflict rapidly raged out of control, with Germany, Russia, Great Britain, and France being drawn into the war by an intricate web of treaties obligating their nations to come to the defence of others, and Western and eastern Fronts opened rapidly along the borders of Germany and Austria-Hungary. The war was greeted across the continent with great rejoicing, as thousands of young men poured into recruitment offices to enlist for the adventure of a lifetime. Most thought they’d be home by Christmas. Instead, a generation died in the muck and slime of places that would be rendered forever infamous: The Somme, Passchendaele, Ypres, Vimy Ridge, Verdun.

“What happens, in my understanding, is at the end of June 1914, when the archduke is assassinated, Austria-Hungary sees that as a moment to have a local war,” Strachan told me. “Not a major war—a local, limited war to crush Serbia, which would reassert its authority in the Balkans. It gets the backing of Germany, and Germany realizes there is a risk of wider war. Germany is behaving in a foolhardy way, absolutely, but is working on the assumption that what it sees as a hostile coalition forming around it—Russia, France, and Great Britain—can be broken, because these countries don’t actually have much in common.” To the contrary, these nations had been the great opponents of the 19th century, not allies. Once it became clear that the war would become a wider war and involve Russia, “at that point, the big drivers in Berlin draw back. They are fearful of this. Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg tries to find a way out. So does the Kaiser. By then, the crisis had acquired a momentum of its own.”

Unlike many historians, Strachan rejects the idea that an Anglo-German arms race triggered the war. He also disagrees with the rationale laid out at Versailles and revived in the ‘60s by German historian Fritz Fischer that the Kaiser’s Germany “prefigured the Third Reich” and that German imperialism was the primary driver of the war. At the time, he told me, Germany “has comparatively little interest in colonies, but is spreading its influence globally through economic power without military power…often in history, I find cockup as good an explanation as conspiracy. In the conditions of the last week of July, when you’ve got countries trying to speak to each other, they’re actually finding it very hard to do so. Some of the ambassadors are on holiday, so there isn’t proper representation in some capitals. Signals are sent by the ambassadors back to their home governments, but they have to encode them and then they have to be decoded on arrival. All that produces loss of time. As time is lost in a fast-moving crisis, so the situation is changed. The relationship between long-term tensions in international relations aren’t in themselves decisive. They explain why war is possible, but they don’t explain why this particular war happens then.”

In fact, Strachan points out, the Great War was not—as many have stated—inevitable. “Between 1905 and 1914, Europe had gone through three major crises, two of them in Morocco and one in Bosnia, and had managed their way out of it,” he pointed out. “They talked about it, they resolved them. It didn’t mean those crises didn’t leave a legacy, but for many people in the summer of 1914, there was absolutely no reason another European crisis couldn’t be resolved in the same way. Today, in 2020, the argument is much more that the war needn’t have happened rather than that the war was bound to have happened.”

***

***

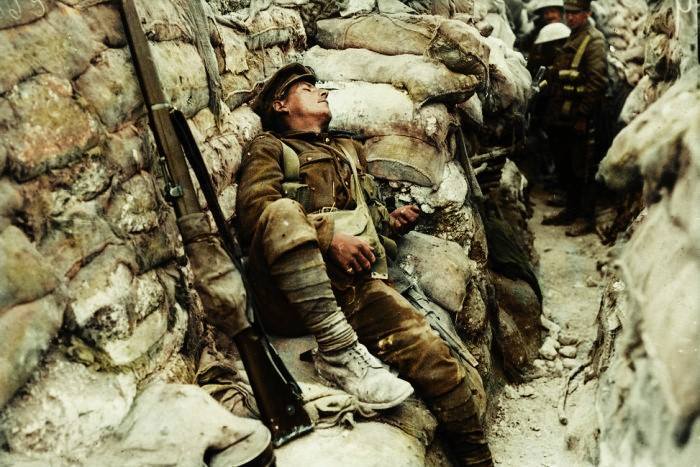

The Great War looms large in our cultural consciousness not only because it transformed the global order and paved the way for the next worldwide conflict but also because, unlike almost any previous war, the personal experiences of the men and women on the frontlines gripped the public imagination. Trench warfare, gas attacks, machine guns, tanks, and heavy artillery were changing the face of warfare, and millions of men were ground to pulp as the gears of history shifted and a new era of combat was birthed in a bloodbath of fire and shattered flesh.

Letters, diaries, and later novels, memoirs, and artwork rendered the brutality and squalid horror in exquisitely painful detail, ripping off the mask of martial glory to expose the true face of battle. Recently, the diary entries of Captain Charlie May, who was killed at the age of 27 on the morning of July 1, 1916, leading his men into action on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, were published, and his scribblings describe life on the frontlines:

January 13, 1916

I long and long to see you, to clasp you in my arms…and I long with all my heart to see my Baby. How I love her. What hopes I have for her, what a sweet girl she will make.

February 25, 1916

Woke up this morning to find the snow pelting down and covering the ground fully five inches deep. Also it was freezing hard. Cotton [a fellow officer] came in to breakfast with us. He brought the little bible which [another soldier] had taken from the body of a dead German. On the fly-leaf in a child’s handwriting the word Dada.

War is very sad. Perhaps the man may have been something to loathe and detest. I do not know. All I am conscious of is that somewhere in his fatherland there is a little child who called him Dada.

June 17, 1916

I do not want to die…the thought that I may never see you or our darling baby again turns my bowels to water. My conscience is clear that I have always tried to make life a joy for you. But it is the thought that our babe may grow up without my knowing her and without her knowing me. I pray God I may do my duty for I know whatever that may entail you would not have it otherwise.

In the early morning hours of July 1, 1916, Charlie took out his diary to write one last entry:

We marched up [to the assembly trench] last night. The most exciting march imaginable. Guns all round us crashed and roared till sometimes it was quite impossible to hear oneself speak. It was, however, a fine sight and one realised from it what gun power really means.

Fritz, of course, strafed back in reply, causing us some uneasiness and a few casualties before even we reached the line. The night passed noisily and with a few more casualties. The Hun puts a barrage on us every now and then and generally claims one or two victims.

It is a glorious morning. We go over in two hours’ time. It seems a long time to wait and I think, whatever happens, we shall all feel relieved once the line is launched. No Man’s Land is a tangled desert. Unless one could see it, one cannot imagine what a terrible state of disorder it is in. But we do not yet seem to have stopped the machine guns. These are popping off all along our parapet as I write. I trust they will not claim too many of our lads before the day is over.

Now I close this old diary down for the next few days since I may not take it into the line. I will keep a record of how things go and enter it up later.

As he put his diary away, the Allied bombardment of the German trenches began again with a roar, lasting for an hour. The officers blew their whistles, and the men followed them up the ladders and over the top. Charlie led B Company, 22nd Manchester Pals Battalion into No Man’s Land in the face of a storm of bullets, and he almost made it to the German lines before he was cut down by a shell. His loyal friend, Private Arthur Bunting, remained with his body for three hours under heavy fire, and then dragged Charlie back to the trenches. His duty to his friend done, he mailed Charlie’s diaries to his wife Maude, who wrote him a heart-rending response: “I don’t know how I shall go through life without him—the loving care and devotion he showered upon baby and me was greater than I can ever put into words.”

Before he died, Charlie had asked his comrade Captain Frank Earles, who had suffered the long months in the trenches with him, to care for his wife and baby daughter Pauline if he was killed. Four years later, Earles married Maude, and made good on his promise to be a devoted and loving husband and step-father to the wife and little girl that Charlie left behind.

For those who did survive, the sights and the smells of battle would follow them for the rest of their lives. Sergeant Jack Dorgan of the Northumberland Fusiliers described what he saw when his position suffered a direct hit from a German shell, leaving him unhurt but striking with such force that two of his comrades were vomited out of their trench. “I found them lying just a few yards away,” he recalled. “They’d had their legs blown off and all I could see when I got to them was their thigh bones. I will always remember their white thigh bones. The rest of their legs were gone. Private Jackie Oliver was one of them, and he was unconscious. I shouted back to the fellows behind me, ‘Tell Reedy Oliver his brother’s been wounded.’”

“So Reedy came and stood looking at his brother, lying there with no legs, and a few minutes later he watched him die. But the other fellow, Private Bob Young, was conscious right to the last. I lay alongside of him and said, ‘Can I do anything for you, Bob?’ He said, ‘Straighten my legs, Jack,’ but he had no legs. I touched the bones and that satisfied him. Then he said, ‘Get my wife’s photograph out of my breast pocket.’ I took it out and put it in his hands. He couldn’t move, he couldn’t lift a hand, he couldn’t lift a finger, but somehow he held his wife’s photograph on his chest. And that’s how Bob Young died.”

Stuart Cloete was commissioned at age 17 as a British schoolboy in 1914, and later described what he saw at the Somme. Burial was often impossible, and so the corpses were everywhere: “In ordinary warfare the bodies went back with the limbers [gun carriages] that brought up the rations, but now there were hundreds, thousands, not merely ours but German as well. [Out in No Man’s Land], the sun swelled up the dead with gas and often turned them blue, almost navy blue. Then, when the gas escaped, the bodies dried up like mummies and were frozen in their death positions…sitting bodies, kneeling bodies, bodies in almost every position, though most lay on their bellies or on their backs. The crows pecked out the eyes and the rats lived on bodies that lay in abandoned dugouts. These rats were very large and quite fearless, their familiarity with the dead having made them contemptuous of the living. One night one fell on my face in a dugout and bit me.”

Sidney Rogerson, also a veteran of the Somme, recalled being constantly told to “keep your head down,” and that “we slunk about from hole to hole, from one piece of cover to the next, not daring, or else forgetting, to look about…our landmarks were wrecked aeroplanes, derelict tanks, dead horses, and even dead men. Churches, houses, woods, and hedgerows had all disappeared. The distance was shrouded by rain and mist, from out of which the boom of gunfire came distant and muffled.”

***

And then there was the poetry. Out of the mud and the ashes and the fire of the Great War some of the most magnificent lines ever penned about battle emerged. Many of these poems were rendered even more poignant because the young men that wrote them did not survive the inferno, giving their verses the haunting air of a pre-written elegy. Wilfrid Owen, a young British soldier who was killed in action at the age of 25 a mere week before the Armistice, wrote a handful of them between August 1917 and September 1918. In Dulce et Decorum Est, he described a gas attack:

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

The Latin lines were taken from Ode 3.2 of the Roman poet Horace and translate to “it is sweet and fitting…to die for one’s country.”

Alan Seeger, the American poet who volunteered to fight for the French Foreign Legion in 1914 and was reported to have been cheering the second wave of advance at the Battle of the Somme as he lay dying of his wounds on July 4, 1916, infused his famous lines with resigned bravado:

I have a rendezvous with Death

At some disputed barricade,

When Spring comes back with rustling shade

And apple-blossoms fill the air—

I have a rendezvous with Death

When Spring brings back blue days and fair.

It may be he shall take my hand

And lead me into his dark land

And close my eyes and quench my breath—

It may be I shall pass him still.

I have a rendezvous with Death

On some scarred slope of battered hill,

When Spring comes round again this year

And the first meadow-flowers appear.

God knows ’twere better to be deep

Pillowed in silk and scented down,

Where Love throbs out in blissful sleep,

Pulse nigh to pulse, and breath to breath,

Where hushed awakenings are dear …

But I’ve a rendezvous with Death

At midnight in some flaming town,

When Spring trips north again this year,

And I to my pledged word am true,

I shall not fail that rendezvous.

Seeger’s comrade Rif Baer described his final moments: “His tall silhouette stood out on the green of the cornfield. He was the tallest man in his section. His head erect, and pride in his eye, I saw him running forward, with bayonet fixed. Soon he disappeared and that was the last time I saw my friend.” Seeger was shot down in No Man’s Land, and he cheered his comrades on as they surged passed him. He was twenty-eight years old.

There are others, of course, including titans such as Siegfried Sassoon and Robert Graves. But there were also poems that highlighted the ocean of pain the millions of dead young men left behind. A couple of years ago, walking through the graveyards of Gallipoli with my wife, I found that sudden tears sprang to my eyes reading the headstone of Private A. Ferguson of the Highland Light Infantry, who was cut down on November 10, 1916 at the age of 26: Who loved you best, They miss you most—loving wife and daughter Mary. Little Mary waited in vain for Daddy to return from Gallipoli, instead watching her mother grieve the loss of the young man she had only just decided to spend the rest of her life with. A poem by Vera Brittain, who served as a nurse and published a best-selling memoir on her experiences during the First World War in 1933, captures the overwhelming sense of loss. It is titled Perhaps, and dedicated to her fiancé Roland Aubrey Leighton, who was killed by a sniper in 1915 at the age of twenty—only four months after she had accepted his marriage proposal:

Perhaps some day the sun will shine again,

And I shall see that still the skies are blue,

And feel once more I do not live in vain,

Although bereft of You.

Perhaps the golden meadows at my feet

Will make the sunny hours of spring seem gay,

And I shall find the white May-blossoms sweet,

Though You have passed away.

Perhaps the summer woods will shimmer bright,

And crimson roses once again be fair,

And autumn harvest fields a rich delight,

Although You are not there.

Perhaps some day I shall not shrink in pain

To see the passing of the dying year,

And listen to Christmas songs again,

Although You cannot hear.

But though kind Time may many joys renew,

There is one greatest joy I shall not know

Again, because my heart for loss of You

Was broken, long ago.

***

But some veterans found it hard to speak of their wartime experiences not because they had been traumatized, but because, as Strachan’s old art master had told him, they had been defined by it and had even, in some instances, enjoyed it in a way they could not quite articulate. “Edmund Blunden, one of the better-known British authors of the First World War, begins The Undertones of War, published a decade on from the war’s end, by saying that not a day goes by when I don’t think about this war and go back to it,” Strachan told me. “And he lived until the 1970s, and his widow said after he died that it was true, every day of his life he referred to that war. And here was a man who had a successful career after the war and had a family and all those things—he ended up being an Oxford don and then a professor at Hong Kong University—so he had plenty going on in his life. So he could have moved on better than he did.”

“One of the striking things about how we commemorate the First World War now is that we focus on the dead—those who didn’t come back rather than those who did,” Strachan observed. “Of course, the vast majority of those who served did come home: 88% of those who put on a uniform came home, 12% died. If you were in an infantry unit or flying in the Royal Flying Corps then your death rate was higher than that, but most came back. So what did they come back to? Some are suffering from shell shock, which has been diagnosed and addressed, although not necessarily in the terms we would use today. It is recognized as a medical condition which needs help and support. What most people want to do, of course, is come home and pick up their lives.”

And that is where things became difficult: “I think the big challenge is that those who go to war, almost by definition, are young men. And for many of them, it’s that move from adolescence into adulthood. If you’re 18 in 1914, then you’re 22 in 1918. If that is your age, you won’t have done anything else in your life. You may have left school at 15 or something, but you probably won’t have a settled path. You won’t have married, you won’t have a steady job, and for those who have stayed in school and gone to university, you haven’t even begun doing some of those things. So then, with the end of the war—and this applies even to those who are older and do have families and jobs to return to—there’s a real sense of loss. They’ve been fighting this war for so long, it’s become so intrinsic to their way of life, for some of them, of course, they’ve reconciled themselves to the thought that they’re not going to survive, that they will never come home—and suddenly, they have to pick up the pieces. They’ve got to go home.”

And this, Strachan pointed out, was more difficult than most imagined. “They’ve got to reengage with their wives and children and they’ve got to go back to a form of work that doesn’t have all those bonds of comradeship or the intensity of life which military service in a war zone generates. Broadly speaking, the older they were, the better they were able to do that because they did have something to go back to. For those who were uncertain of direction, they really had to think again, and some found it very difficult indeed to think where their lives would go from here. And some never got there…I’ve encountered plenty of old soldiers of the First World War. Some of them said they wouldn’t talk about the war—but we have to remember that there were many different responses to the war. Some of them talked about it as if it was one of the most exciting periods of their lives, and part of the problem [was] precisely that—they [didn’t] know quite how to move on from that, when you’ve been through something that intense…there was nothing else in their lives, however much they wanted normal civilian lives going on in the ways we would expect—nothing quite so exciting ever happened again. I think that was a powerful positive as well as negative force.”

There was also the fact that as time went on, it became clear that the Great War had not been the final one. “The war ends unsatisfactorily on all sorts of levels, and probably doesn’t fully end until 1923,” Strachan explained. “There’s still British units in the Middle East up until 1923. They come back and then, 1928-29, having begun to put their lives together, the slump [Depression] happens, and suddenly everything is up for grabs again. And then during the 1930s, they have to come to grips with the fact that actually, this hasn’t been the War to End All Wars. I often think about my grandfather. My grandfather served 1914-15, was seriously wounded—that was the end of his frontline service—served in the army for the rest of the war, marries, has children, his wife dies, my father is the one surviving child who gets to adulthood, and then in 1939, my father’s off to the war—the one surviving close relative. What was he thinking? When he’d done all this, for his son’s generation? It must have been extraordinarily difficult for those men when it happened again. And of course he, like many others, finds himself back in uniform again. He’s sitting in a perfectly safe and boring job doing something for the War Office, but the point is between 1939 and 1945, he’s back being a captain in the British Army, well into his forties when the war breaks out.”

“You didn’t expect to have to do it twice.”

***

What impact did the Great War have on Christianity in the West? Some historians and writers believe that the “spiritual mobilization” of the clergy on both sides of the conflict, with priests and pastors assuring their flocks that God was on their side, did much to crush the credibility of the churches after the war and snapped the spine of organized religion in Europe. Hew Strachan’s view is that it is much more complicated than that. “Church attendance is already declining before 1914,” he told me. “Europe is more secular than our sort of cozy image of 19th century European countries allows for. But of course, what there isn’t is a large population of other faiths, non-Christian faiths, as there is in Europe today. A multi-faith environment is absent. Even if there are plenty of people without any faith, formally speaking, countries can identify themselves as Christian countries.”

Dr. Adrian Gregory, an Oxford historian, told me that fundamentally Christian assumptions undergirded events on an even more visceral level. Today, he noted, most people would find the idea of sacrificing one’s life for a greater cause to be “almost terrifyingly fanatical.” But back then, “it is a cultural assumption of many societies in the early 20th century that there is something greater than the individual life. This is transmitted to a large extent through religion. And to some extent, it also rests on a near-universal assumption of an afterlife. It may be impossible to grasp why people are willing to tolerate what they do, whether it be soldiers on the front lines risking their lives or their families at home accepting that they are giving up their relatives to this military Moloch without understanding that people genuinely did not think that death was the end…without a knowledge of the Bible, you won’t make much sense of it.” Even while clergy complained of a dearth of doctrinal knowledge, Gregory observed, “they are, at the same time, a hymn-singing army. Even the popular songs are all parodies of hymns.”

Initially, many Europeans became more religious. “Religion becomes important,” Strachan explained. “What’s interesting is that as the war breaks out, church attendance soars in that opening week of the war in August 1914. People do feel the need to go to church before they go to war, and go as a family, because they don’t know if the member of the family that is going to war is going to come back. So the church plays that sort of consoling role, which gives meaning. Undoubtedly, too, by the end of the war, there are many people who have lost their faith because of what they’ve seen and [what] war means, and that includes people who are well-known pastors of one form or another who really struggle with issues of faith when they see the appalling things that are being inflicted on humanity.”

Religion shaped the Great War on both the macro and micro level. The Catholic Church was in a particularly difficult position due to the fact that large bodies of Catholics were on either side of the conflict—the Belgian cardinal made things even more difficult by praising patriotism in his 1914 Christmas speech, giving it a spiritual quality. Russia used the Orthodox Church as an agent of national identification, and briefly, after the fall of the Tsar in 1917, the Orthodox Church believed that they would experience a period of liberation and revival. Instead, the Bolshevik Revolution and decades-long persecution followed. On a national level, Protestant Germany was upset that England, a Protestant country, was willing to go to war against them. As Strachan put it: “Faith matters, but war comes first, and then faith is conscripted.”

I asked both Strachan and Gregory whether they believed that the Great War was a defining factor in the death of European Christianity. Strachan told me that it was difficult to say: “Is this the tipping point where Christianity is really being demoted from its central place in European life, or is this already happening? Well, this is true of many arguments. Is modern art a product of the First World War, or no, because we can see people like Picasso painting in cubist forms before the First World War? But does the First World War, as in these other cases, provide a vehicle for popularizing that? The answer is yes. People are looking for meaning where they’re struggling to find meaning.”

Gregory was blunter. “I don’t buy that. Yes, there are people who lose their faith as a result of the war. But for every person who loses their faith as a result of the war, there’s probably a person who finds faith as a result of the war. There are people who look for religious meaning in the war—a lot of them. [So] on the level of belief, no. But the war does do certain things that are important in the realm of the intersection between religion and politics. One thing that the war does is it brings down sacral monarchies, monarchies based on the idea of the divine right.”

Gregory believes that the churches didn’t really begin to empty out across the West until the 1960s, noting that in terms of church attendance, getting married in church, and Sunday school attendance, Great Britain was a very religious society right up until 1950. “And then, almost within my own lifetime actually, there is a radical de-sacralization. Even then, you have to allow for evangelical revivals and other complexities. Regular religious worship declines very, very rapidly. But more recently than we tend to give it credit for.”

Philip Jenkins, the author of The Great and Holy War: How World War I became a Religious Crusade, detailed how the war was cast in religious terms, supported by the clergy, and the fallout that inevitably came when the Great War finally ended:

If we focus on the short-term and concentrate on Europe, the conflict’s impact seems disastrous. Russia, in 1914, was home to nearly one quarter of the world’s Christians; the Bolshevik Revolution and the ensuing murderous upheaval nearly obliterated the Orthodox Church. Germany’s dominant Lutheran Church survived, but at the price of compromises with a secular messianic state. Christianity went dormant in both countries, and monstrous ideologies that centered on a different kind of “holy nationhood” filled the void.

Yet our conclusion changes when we shift our attention from Europe to the broader world. Most notably, World War I set in motion events that led eventually to the decolonization of Africa. Christianity in that continent was finally disentangled from the political ideologies of the colonizing powers. Although no one could have predicted it in 1918, African Christianity would flourish in subsequent generations, a trend that shows no sign of slowing: It is assumed that, by the middle of the 21st century, one-third of all Christians will live there. In a parallel development, the war precipitated the collapse of the Ottoman Empire—long the political focal point of Islam. This forced Muslim thinkers and religious leaders to search for a new source of authority. What followed was the eventual rise of modern Islam as we perceive it today: “assertive, self-confident, and aggressively sectarian.”

So did World War I kill European Christianity? The answer is complicated, but one thing is largely agreed upon: The moral order of society prior to the Great War was Christian, and that order was utterly destroyed in the inferno.

***

For the 100th anniversary of the Armistice that ended the Great War at 11:00 AM on November 11, 1918, London’s Imperial War Museum opened an exhibit called “Making a New World.” The exhibit featured a sound recording of the last few moments of the First World War, tracking the very moment the guns finally fell silent along the River Moselle on the American Front. Up to a minute before the war was over, the guns were still belching out their shells, crashing like thunder. Then there is a final barrage, and then an echo rolls across the sky and slowly fades. Then, for a few long seconds, nothing but the wind and the river. And then, the birds begin to sing again, as if the guns had never roared. One would have thought their fear would last, but it is as if they were waiting to herald this moment, to remind everyone that not all Creation had been ripped asunder during those four long, terrible years.

It was a reminder that was needed. Four empires had collapsed: the Russian Empire had fallen to the Bolsheviks, assisted by Germany, in 1917; the German and Austro-Hungarian Empire came to an end in 1918; and, after attempting a total genocide of the Armenian people, the Ottomans limped along and collapsed in 1922, giving way to what would become modern Turkey. Almost ten million military servicemembers had died, and another ten million civilians were killed. An additional 21 million people were wounded.

According to Strachan, there are three primary ways in which “the First World War lives with us now.” The first is the impact of the Russian Revolution, which would shape the rest of the twentieth century. The second was the emergence of the United States as a world power, which “initially had no interest in joining the war, join[ed] in 1917, and in 1919 Woodrow Wilson aspired to create a new international order [to] ensure peace in the future. It fail[ed], but the general ideas did not.” And finally, there was the Middle East: “The partition of the Ottoman Empire, the allocation of territories to Britain and France, the encouragement of Arab nationalism—all have very current legacies, as had the Balfour Declaration and the eventual creation of the State of Israel. Maps were drawn that have created what we have now.” For some independence movements, the Great War culminated in the fulfilling of long-held dreams. In places like Canada, the US, and Britain, there was a sense of continuity, while in Germany, the century would hold constant and violent change. The 1919 Treaty of Versailles, in fact, would humiliate and cripple Germany so badly that a second world war would be needed to address it.

My final question to Sir Hew Strachan was a simple one: What do we all still get wrong about the Great War that is dangerous to our understanding of the present? On this, he was emphatic: “My biggest concern is that even good historians tend to look at history with hindsight, in the rear-view mirror, and tend to assume arrogantly that we wouldn’t do these things. Because we now know the First World War was as awful as it was, we [think] we never would have done these things. Which is just nonsense. You don’t live history that way. You have no idea what’s going to happen in the next five minutes, let alone the next five days, let alone the next five weeks. Of course, you have a plan, but sometimes things happen by surprise that you can’t anticipate. In the First World War, they’re encountering that the whole time.”

“My most important point,” he told me, “is to avoid the arrogance that we have because we now know and to realize that we ourselves are just as capable of mucking things up. Because if we don’t do that, there’s not much point in thinking about history at all. One of the ways the war is helpful to us is because it teaches us precisely that sort of humility. I’m often asked: What does the First World War tell us of the possibility of a major war in our own times? And I would say: Well, it tells us a great deal, but not in the way you think. If you think two great powers, like the United States and China, are going to pick a fight, the chances are that’s not the case.” Instead, Strachan believes, global conflict is more likely to erupt as a result of the superpowers being pulled into a local conflict—just as it unfolded in 1914.

With the last eyewitnesses gone, the Great War is now firmly planted in the annals of history, although, as Strachan points out, it “is still with us in all sorts of ways. When I began writing about the First World War, one of my claims at the time was that we’ve now reached a point where the veterans—although there were still some alive at the time—are no longer dominating the narrative. I felt you could really tackle this as a historian and not get caught up in the immediacy of it. When we got to the centenary in 2014, I thought: Well, I remember the 50th anniversary of the war’s outbreak, and now I am further away from that 50th anniversary then I was from the war itself. It’s not that far away. I have a friend whose father served in the First World War. He’s a bit younger than I am, and obviously his father was a bit older.”

In 1919 as the Paris Peace Conference ended and the Treaty of Versailles was signed by leaders both ebullient and crestfallen, the world looked forward to the new era ahead. But as a Great Depression and a Second World War would illustrate, the War to End All Wars had merely been an opening act to the bloodiest of centuries.

This was incredibly well written.

Thank you!

As usual… a tour de force…..

thank you sir!

“So did World War I kill European Christianity? The answer is complicated, but one thing is largely agreed upon: The moral order of society prior to the Great War was Christian, and that order was utterly destroyed in the inferno.”

Another ‘Tour de Force’ by Sir Jon, excellent analysis and reference sources. One wonders if the recent “Covid Wars” has had a similar devastation on the local church. Regional Wars gained a momentum of its own, without strong or brave Church leaders to withdraw from madness.

This is a fine piece of writing, sir!

Thank you!