Blog Post

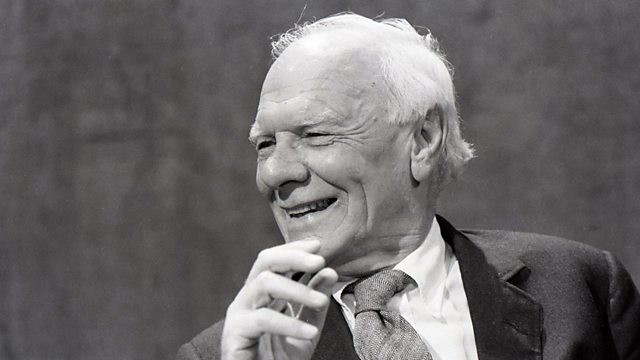

What today’s conservative intellectuals can learn from Malcolm Muggeridge

By Jonathon Van Maren

Solomon tells us that “there is no new thing under the sun,” and this is also true for the delusions of our postmodern progressives. While today’s revolutionaries seem more insane than their forebears, with our binary-smashing eunuchs and their crusades against biology, it is important to remember that the sinister gullibility of our elites remains unchanged.

I was reminded of this recently when reading Malcolm Muggeridge’s magnificent 1972 memoir, Chronicles of Wasted Time, in which he describes the infatuation of Western intellectuals with the genocidal Soviet Union. In 1932, while covering the Soviet experiment in Moscow, Muggeridge and several journalist colleagues held a contest “to see who could produce the most striking example of credulity among this fine flower of our Western intelligentsia.”

Muggeridge nearly won when he convinced Lord Marley that the endless bread lines were not a result of shortages, but rather were “permitted by the authorities because it provided a means of inducing the workers to rest when otherwise their zeal for completing the Five-Year Plan in record time was such that they would keep at it all the time.” It has always taken an unreasonable amount of faith to believe in allegedly progressive ideologies, both then and now.

As Christendom’s twilight gives way to the post-Christian night, it has become a popular pastime of conservative writers to muse on whose past predictions qualify as prophecies. Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, and Neil Postman are widely agreed upon; Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, too, for those who have bothered to read his still-essential Warning to the West. There are other candidates as well. For instance, Christopher Lasch and Alan Bloom, who laid out the revolt of the elites and the collapse of academia.

In addition to these, I would like to echo biographer Gregory Wolfe’s proposal that it is past time for Malcolm Muggeridge to get his due. Muggeridge has been the subject of three major biographies thus far—by Wolfe, Richard Ingram, and Ian Hunter. Of the three, only Wolfe’s 2003 work can be considered definitive.

Wolfe lays out the narrative arc of Muggeridge’s life and reveals him to be a lifelong seeker who long resisted the Christianity that would define his last years, whilst debunking the widely held belief that Muggeridge was simply a hedonistic raconteur who converted once the passing of his youth had dulled the desires of the flesh. Even Christopher Hitchens, who wrote a book trashing Muggeridge’s beloved Mother Teresa, observed that “the cumulative effect of Wolfe’s narrative … is so serious and so genuine that the biography ultimately forces a reconsideration of its subject.”

Wolfe’s case for a reappraisal of Muggeridge’s legacy is compelling. His contemporaries, from Orwell to Greene, have received their due. Muggeridge has not, despite his astonishing record of prescient predictions. This is in part because Muggeridge was a journalist and television presenter rather than a philosopher, theologian, or successful novelist. He was also a profoundly modern man: hard-edged, satirical, and possessing a profound sense of absurdity that frequently bordered on cynicism. Despite what he called his “Niagara of words,” many now remember him primarily as an omnipresent fixture on the BBC rather than as a writer.

As a journalist, Muggeridge managed to be nearly everywhere. He spent time in India, corresponded with Gandhi, and correctly predicted that the days of the British Raj were numbered. He was one of only a handful to report on the Holodomor in Ukraine, covered the League of Nations from Geneva, and was one of the few who saw war with Germany coming. As an MI6 agent, he engaged in daring escapades in Mozambique, made it to France for the Liberation, and toured the scorched remains of Hiroshima with a delegation that included Emperor Hirohito. He covered the segregation battles in Little Rock, Arkansas, politics in Washington, D.C., and even bumped into the Beatles in a small bar before they went big. As a BBC host, he interviewed every major figure of his time, from Solzhenitsyn to Stalin’s daughter, Svetlana.

Wolfe identifies several reasons for Muggeridge’s descent into relative obscurity. Much of what he correctly predicted is now so widely accepted that most have forgotten his prescience. Additionally, Muggeridge’s decision to become a television personality enormously damaged his literary output. To read his history The Thirties, or his two-part autobiography (he never got around to the long-promised final volume), or any of his collections of essays is to be reminded of the sort of historian and social commentator Muggeridge could have been had his self-confessed laziness not drawn him to the easy money offered by the BBC.

He signed many contracts for books he never wrote and agreed to write others he never finished. He was often tortured by guilt for producing comparably little that was lasting. It is true that he was a brilliant interviewer and a sparkling conversationalist, but his documentaries are nearly impossible to obtain and only a fraction of his massive television output can be found on YouTube. Much of his life’s work is now inaccessible to the public—and even if it were accessible, I suspect he would not have the same online cult following that other commentators—such as the Hitchens brothers or William F. Buckley Jr.—have acquired. Muggeridge was simply too complicated a man to have a natural constituency.

Indeed, for most of his life, Muggeridge was a tormented, Augustinian figure plagued by cycles of depression, self-doubt, heavy drinking, and sexual recklessness. Most recently, Muggeridge made the news in 2015, when historian Jean Seaton revealed in her book, Pinkoes and Traitors: The BBC and the Nation 1974-1987, that he was given the nickname “The Pouncer” for his reputation as a groper. Muggeridge’s #MeToo footnote, however, scarcely made a ripple—there were no statues to topple and no legacy to attack, so nobody much cared. People no longer recognised his name.

READ THE REST OF THIS COLUMN AT THE EUROPEAN CONSERVATIVE