Blog Post

The heartbreaking real-life inspiration for Winnie-the-Pooh

By Jonathon Van Maren

As my wife and I read through books with our children, my five-year-old daughter has a favourite question: “Is she real, Daddy?”

Ever since we read Little House on the Prairie and she discovered that Laura Ingalls Wilder had, in fact, existed, Charlotte has been obsessed with discovering which of the stories we read her contain real people and which ones are “made up.” Only once has she refused to believe me. That’s when I told her that Christopher Robin in A.A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh books was a real little boy. To convince her, I actually had to show her Christopher Robin Milne’s autograph in my copy of his memoir The Path Through the Trees in my library. Her blue eyes grew huge.

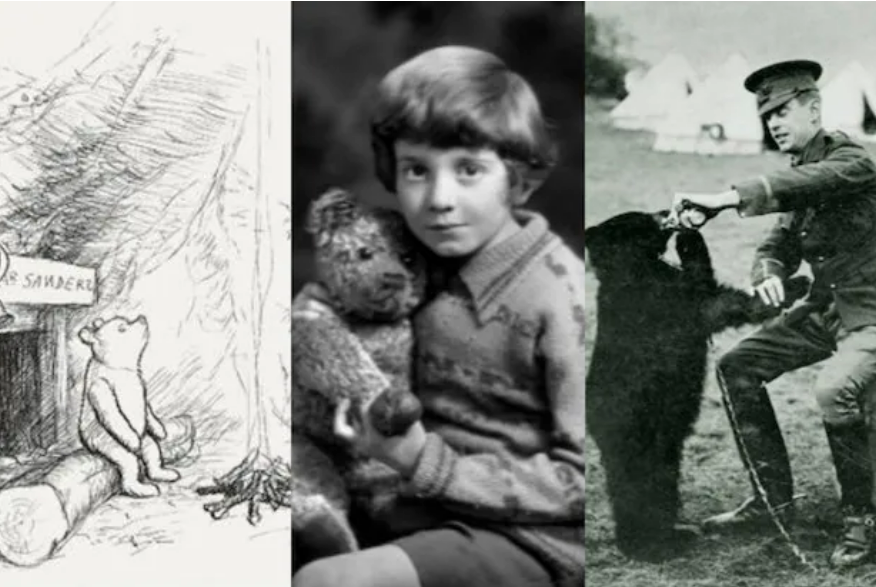

Of course, the other characters in Milne’s classics aren’t real—not really. A.A. Milne based Winnie the Pooh and the others on his son’s stuffed animals, now on permanent public display in the New York Public Library (England has attempted to get them back to no avail, claiming that they are a “national treasure). But there was, in fact, a real “Winnie the Bear.”

A couple of years ago on a stopover in Winnipeg, I visited Assiniboine Park, where the Pavilion hosts a permanent Pooh Gallery. In that gallery are to be found a number of original photographs of a certain black bear by a certain Lieutenant Harry Coleburn, who served during World War I in the Royal Canadian Army Veterinary Corps. The exhibit contains Coleburn’s diaries, a collection of documents, and a handwritten letter from Christopher Robin Milne when he was he was still a boy. A short walk away there is a statue of Winnie as a bear cub dedicated to the “children of the world” by sculptor William Epp. A plaque next to the statue tells the story:

On August 24, 1914, while en route overseas during World War I, Lieutenant Harry Coleburn, V.S., of the 34 Fort Gary horse regiment of Manitoba, purchased a black Canadian bear cub at White River, Ontario. He named her Winnie, after Winnipeg, his home town. The bear became the pet of the soldiers. While Lieutenant Coleburn served in France, she was left in the care of the London Zoo. In 1919, he gave her to the zoo where she was visited and loved by many, including the author A.A. Milne and his son Christopher.

In 1920, A.A. Milne gave the fictional character Winnie the Pooh, named after Lieutenant Coleburn’s bear, to Christopher Robin and his friends for posterity. Winnie died at the London Zoo on May 12, 1934.

Anyone who has read A.A. Milne’s books—Winnie the Pooh, The House at Pooh Corner, When We Were Very Young, and Now We Are Six—knows that they are, simply put, a treasure. Very few books manage to be whimsical, truthful, and yet so funny that even the chapter titles can make you laugh out loud. A.A. Milne’s fantasy world, located in the forest behind his countryside house (the Hundred Acre Wood) and inhabited by his son Christopher Robin and his stuffed animals, has been a source of fascination for generations now. Milne had actually fancied himself a “serious” writer, not a children’s author—but his stories were just what England needed in the days following the First World War. Milne, many said, taught them how to laugh again.

Milne also captured that sad, poignant moment when one is just old enough to realize that he is leaving childhood behind, but isn’t quite sure that he wants to. His description of Christopher Robin’s farewell to Pooh as he tries to explain to the bear that he must go off to school, grow up, and become an adult—that he can no longer enjoy doing their favourite thing (“Nothing”)—are some of the most beautiful lines in children’s literature:

Then, suddenly again, Christopher Robin, who was still looking at the world, with his chin in his hands, called out “Pooh!”

“Yes?” said Pooh.

“When I’m—when—Pooh!”

“Yes, Christopher Robin?”

“I’m not going to do Nothing any more.”

“Never again?”

“Well, not so much. They don’t let you.”

Pooh waited for him to go on, but he was silent again. “Yes, Christopher Robin?” said Pooh helpfully.

“Pooh, when I’m—you know—when I’m not doing Nothing, will you come up here sometimes?”

“Just me?”

“Yes, Pooh.”

“Will you be here too?”

“Yes, Pooh, I will be, really. I promise I will be, Pooh.”

“That’s good,” said Pooh.

“Pooh, promise you won’t forget about me, ever. Not even when I’m a hundred.”

Pooh thought for a little. “How old shall I be then?”

“Ninety-nine.”

Pooh nodded. “I promise,” he said.

Still with his eyes on the world Christopher Robin put out a hand and felt for Pooh’s paw. “Pooh,” said Christopher Robin earnestly, “if I—if I’m not quite—” he stopped and tried again—”Pooh, whatever happens, you will understand, won’t you?”

“Understand what?”

“Oh, nothing.” He laughed and jumped to his feet. “Come on!”

“Where?” said Pooh.

“Anywhere,” said Christopher Robin.

So they went off together. But wherever they go, and whatever happens to them on the way, in that enchanted place on the top of the Forest, a little boy and his Bear will always be playing.

It is fitting that the statue of Winnie the Bear stands in the middle of a playground, constantly surrounded by children who, like Christopher Robin, are filling their beautiful sunny days with Nothing. Because after the wonder of childhood—if you are blessed to have such a thing—comes the death of innocence and then the rest of life.

So it was for Christopher Robin, too, who was brutally bullied throughout his boarding school days because of the childhood his father had immortalized in the wildly famous Winnie the Pooh books. It was something that he only made peace with upon the arrival of his own daughter, a little girl with cerebral palsy named Clare Milne, who would receive the endless love and devotion of her father Christopher Robin–who, after all, understood what childhood was all about.